Endodontic Medicine

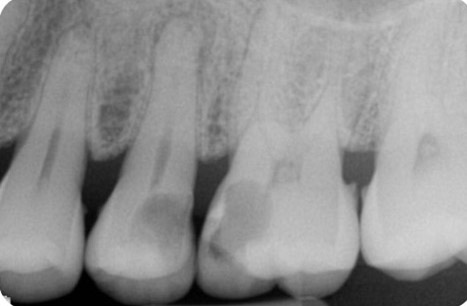

Endodontics is the study and treatment of disorders of the neurovascular tissue within the interior of teeth, including the pulp chamber and roots. These disorders occur most often when the root canal becomes infected as a result of extension of dental caries into the pulp chamber. With infection of the neurovascular tissue, necrosis can occur, and the disease process can progress to involve the entire root canal system (Figure 1). Pain, often intense, will be experienced by the affected individual. As necrotic debris becomes located at the apex of the root in the alveolar bone, the infection can extend beyond the local area to include the more coronal periodontal tissues (Figure 2). Obvious clinical swelling and suppuration can be present. The bacteria that characterize these acute lesions are Gram-negative anaerobes. These infections can be associated with systemic symptoms, including fever and malaise.

The role of oral infection/oral inflammation as risk factors for chronic diseases and disorders has generated significant attention from both the dental and medical communities. The focus of this research has been on the role of periodontal disease (periodontitis), and this field of study has been termed “Periodontal Medicine”. However, endodontic lesions can also be an important source of oral infection, and consequently inflammation, and the relationship to specific chronic diseases has been examined. This area of investigation can be referred to as “Endodontic Medicine”.

An endodontic infection that results in necrosis of the contents of the pulp chamber and canals will eventually appear on a radiograph as radiolucent area at the root apex. To illustrate the inflammatory potential of apical lesions, a study of C-reactive protein (CRP; an acute phase protein that has been associated with the systemic inflammatory burden) and interleukin-6 (IL-6; an important pro-inflammatory mediator) were evaluated in asymptomatic periapical lesions and in the periodontal ligament from teeth of unaffected patients1Garrido M, Dezerega A, Bordagaray MJ, Reyes M, Vernal R, Melgar-Rodriguez S, et al. C-reactive protein expression is up-regulated in apical lesions of endodontic origin in association with interleukin-6. J Endod. 2015;41(4):464-9.. Both types of tissue expressed CRP and IL-6, with distinctly higher levels in the tissues from periapical lesions. The authors concluded that apical lesions (apical periodontitis, AP) could contribute to persistent low-grade systemic inflammation.

A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the association of endodontic lesions and the concentration of inflammatory mediators in the systemic circulation2Georgiou AC, Crielaard W, Armenis I, de Vries R, van der Waal SV. Apical periodontitis is associated with elevated concentrations of inflammatory mediators in peripheral blood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod. 2019;45(11):1279-95 e3.. A total of 20 studies were included. While there was a great deal of heterogeneity in study design, the conclusion was that persons with apical periodontitis had higher concentrations of inflammatory mediators (i.e. CRP and IL-6) than controls subjects without AP. Furthermore, the complement system is a group of proteins that when cleaved help the body eliminate microorganisms. Elevated levels of certain complement components (i.e. C3) is indicative of an active infection. After endodontic treatment, the concentration of C3 in blood was reduced. The authors concluded that apical periodontitis could contribute to systemic inflammation. These lesions generally are localized and would be a source of low-grade inflammation. However, without treatment this source of inflammation could persist for lengthy periods of time.

An analysis of the leukocyte (white blood cell) concentration in blood related to endodontic infection was studied using an animal model. Three groups were established: no, one and four apical lesions3Samuel RO, Gomes-Filho JE, Azuma MM, Sumida DH, de Oliveira SHP, Chiba FY, et al. Endodontic infections increase leukocyte and lymphocyte levels in the blood. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(3):1395-401.. After 30 days they observed that the group with multiple lesions had higher concentrations of leukocytes as well as and the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) than either the no lesion or one lesion group. With the understanding that this is an animal model, the conclusion was that multiple endodontic lesions can alter the systemic inflammatory response, and thereby adversely affect general health.

The relationship of endodontic lesions to certain chronic disease has been examined. The focus has been on cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes mellitus (DM)

Endodontic lesions and cardiovascular disease

Studies have identified an association between endodontic lesions and CVD. A review of this association was published in 2017 and identified 19 articles published between 1997 and 2016. Thirteen of the 19 studies reported a positive association, 5 of 19 did not report any association, and one study reported an inverse association4Berlin-Broner Y, Febbraio M, Levin L. Association between apical periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review of the literature. Int Endod J. 2017;50(9):847-59.. A number of these reports, as well as studies published after this review, are worth examining in greater detail.

An early report evaluated this relationship in the Veteran Administration Dental Longitudinal Study. A total of 708 male patients were evaluated over a 32-year period. A previous diagnosis (at baseline) of CVD was a reason for exclusion. Mean age of the participants was 47.4 years. Thirty five percent had at least one endodontic lesion and 24% were diagnosed with CVD during the follow-up period. They observed that for younger individuals, the presence of an endodontic lesion was associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). As an example, for every 3 years of exposure (presence of an endodontic lesion) the increased time to diagnosis of CHD was 1.4 times faster as compared to individuals who did not have an endodontic lesion5Caplan DJ, Chasen JB, Krall EA, Cai J, Kang S, Garcia RI, et al. Lesions of endodontic origin and risk of coronary heart disease. J Dent Res. 2006;85(11):996-1000..

A study of endodontic lesions and CVD risk from Austria examined the degree of calcification of the aorta (referred to as the “atherosclerotic burden”). This study was unique in that all 531 individuals (mean age of 50 years) received computed tomography of their entire body for medical reasons, and these images were then evaluated for both calcification of the aorta and apical periodontitis6Petersen J, Glassl EM, Nasseri P, Crismani A, Luger AK, Schoenherr E, et al. The association of chronic apical periodontitis and endodontic therapy with atherosclerosis. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18(7):1813-23.. Persons with one or more endodontic lesions had nearly twice the atherosclerotic burden compared to those without a lesion (0.32 ml vs 0.17 ml; p<.05). The atherosclerotic burden was observed to increase with age and the number of untreated endodontic lesions; but not with the number of treated lesions (completed endodontic therapy). Regression analysis identified age, AP without endodontic treatment, being male and caries as determinants of the atherosclerotic burden. Endodontic therapy was seen to eliminate the adverse effect of endodontic involvement on the atherosclerotic burden.

An in-depth study of the association of endodontic lesions and CVD examined the nature of the CVD (none, stable and acute coronary syndrome as determined by angiography). Endodontic status was reported as no apical changes, a widened periodontal ligament in the apical area and an apical rarefaction. Regression analysis was used to determine associations. They concluded that endodontic lesions were an independent risk factor for CVD, with the strongest association between untreated endodontic lesions and the acute coronary syndrome7Liljestrand JM, Mantyla P, Paju S, Buhlin K, Kopra KA, Persson GR, et al. Association of endodontic lesions with coronary artery disease. J Dent Res. 2016;95(12):1358-65.. A study from Sweden demonstrated an even stronger association between apical periodontitis and CVD, with an odds ratio of 3.83 (p = 0.025)8Virtanen E, Nurmi T, Soder PO, Airila-Mansson S, Soder B, Meurman JH. Apical periodontitis associates with cardiovascular diseases: A cross-sectional study from sweden. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17(1):107..

Nevertheless, a subsequent review and meta-analysis of the association of endodontic lesions and CVD used strict criteria for inclusion into the analysis9Segura-Egea JJ, Castellanos-Cosano L, Machuca G, Lopez-Lopez J, Martin-Gonzalez J, Velasco-Ortega E, et al. Diabetes mellitus, periapical inflammation and endodontic treatment outcome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17(2):e356-61.. The conclusion was that study designs and analysis of the data can be questioned, and well-designed longitudinal studies of this association were needed.

Endodontic lesions and diabetes mellitus

The relationship between periodontal disease and DM is bi-directional and has been well documented in both the dental and medical literature. The relationship between endodontic lesions and DM is not as well recognized, but there is an expanding literature on this association, and all dental clinicians should be aware of this relationship.

The association of endodontic lesions and DM has been summarized in a number published reviews. An earlier review (2012) examined both animal and clinical studies9Segura-Egea JJ, Castellanos-Cosano L, Machuca G, Lopez-Lopez J, Martin-Gonzalez J, Velasco-Ortega E, et al. Diabetes mellitus, periapical inflammation and endodontic treatment outcome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17(2):e356-61.. The animal models (of both type 1 and type 2 DM) indicated that diabetes was associated more root resorption, more severe resorption of the bone at the apex of teeth and a greater inflammatory response in the pulpal tissues following pulp exposure. Subsequent clinical reviews came to similar conclusions9Segura-Egea JJ, Castellanos-Cosano L, Machuca G, Lopez-Lopez J, Martin-Gonzalez J, Velasco-Ortega E, et al. Diabetes mellitus, periapical inflammation and endodontic treatment outcome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17(2):e356-61.10Segura-Egea JJ, Martin-Gonzalez J, Castellanos-Cosano L. Endodontic medicine: Connections between apical periodontitis and systemic diseases. Int Endod J. 2015;48(10):933-51.11Segura-Egea JJ, Martin-Gonzalez J, Cabanillas-Balsera D, Fouad AF, Velasco-Ortega E, Lopez-Lopez J. Association between diabetes and the prevalence of radiolucent periapical lesions in root-filled teeth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20(6):1133-41.12Cintra LTA, Estrela C, Azuma MM, Queiroz IOA, Kawai T, Gomes-Filho JE. Endodontic medicine: Interrelationships among apical periodontitis, systemic disorders, and tissue responses of dental materials. Braz Oral Res. 2018;32(suppl 1):e68.13Segura-Egea JJ, Cabanillas-Balsera D, Jimenez-Sanchez MC, Martin-Gonzalez J. Endodontics and diabetes: Association versus causation. Int Endod J. 2019;52(6):790-802.14Cabanillas-Balsera D, Martin-Gonzalez J, Montero-Miralles P, Sanchez-Dominguez B, Jimenez-Sanchez MC, Segura-Egea JJ. Association between diabetes and nonretention of root filled teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J. 2019;52(3):297-306.15Perez-Losada FL, Estrugo-Devesa A, Castellanos-Cosano L, Segura-Egea JJ, Lopez-Lopez J, Velasco-Ortega E. Apical periodontitis and diabetes mellitus type 2: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2).16Gupta A, Aggarwal V, Mehta N, Abraham D, Singh A. Diabetes mellitus and the healing of periapical lesions in root filled teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J. 2020., and reported an association of more expansive apical lesions with increased glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and inflammatory cytokines in blood.

A review published in 202015Perez-Losada FL, Estrugo-Devesa A, Castellanos-Cosano L, Segura-Egea JJ, Lopez-Lopez J, Velasco-Ortega E. Apical periodontitis and diabetes mellitus type 2: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2). also included both animal and human clinical studies. Analysis of the clinical studies indicated that if a person had a diagnosis of type 2 DM, the increased risk of having a tooth with apical periodontitis was 1.17 (p=0.02), and the increased risk of a patient having at least one tooth with apical periodontitis was 1.55 (not significant).

Several individual studies are worth mentioning. Evaluation of the relationship of apical pathology to diabetes status compared patients without DM to those with disease (both metabolically well-controlled and poorly controlled patients17Smadi L. Apical periodontitis and endodontic treatment in patients with type ii diabetes mellitus: Comparative cross-sectional survey. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2017;18(5):358-62.). AP was more commonly seen in patients with DM vs. those without DM (13.5% vs 11.8%). In addition, patients with DM had a greater number of teeth that received endodontic therapy vs. the controls (4.2% vs. 1.8%; p = 0.001). Of interest, patients with poorly controlled DM had a greater prevalence of AP vs. those with well controlled DM (18.3 vs. 9.2; p = 0.001). Earlier studies have shown that patients with poorly controlled DM demonstrated larger periapical lesions compared to patients without DM. Further, when compared to controls, healing followed endodontic therapy was delayed for patients with DM18Rudranaik S, Nayak M, Babshet M. Periapical healing outcome following single visit endodontic treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8(5):e498-e504..

Lastly, patients with DM are prone to infection with the fungus Candida albicans19Gomes CC, Guimaraes LS, Pinto LCC, Camargo G, Valente MIB, Sarquis MIM. Investigations of the prevalence and virulence of candida albicans in periodontal and endodontic lesions in diabetic and normoglycemic patients. J Appl Oral Sci. 2017;25(3):274-81.. An increase presence of C. albicans was observed in periodontal sites and samples collected from the root canal in patients with DM. These data suggest a possible role of this fungal species in the pathogenesis of both periodontal disease and endodontic infections when DM is present.

Conclusions

This review of “Endodontic Medicine” has suggested the following conclusions:

- There is an association between endodontic lesions and CVD, and endodontic lesions and DM. Cause and effect cannot be determined because most of the studies are cross-sectional.

- The mechanisms that account for the association of apical periodontitis and CVD and DM are likely similar to those that account for the association of periodontitis and CVD and DM. Specifically, periapical infection elicits a host inflammatory response, which can contribute to the systemic inflammatory burden.

- Conceptually, the relationship between AP and DM appears to be bidirectional, i.e. AP can contribute to the risk for DM via an increased systemic inflammatory burden, and DM may contribute to the severity of AP. However, longitudinal studies are required to confirm this statement.

- All patients seen in the dental office are evaluated for periodontal disease and endodontic problems. This evaluation takes on special importance for dental patients with a diagnosis of CVD and/or DM. The prevalence and severity of endodontic lesions is higher in these patients, and when present these lesions can contribute to the systemic inflammatory burden. By extension, caries prevention and treatment of existing endodontic lesions should be emphasized.

- There is no evidence that either CVD or DM contributes directly to the development of apical periodontitis. However, in poorly controlled DM xerostomia can occur, which can lead to an increased caries rate (specifically root caries). If the carious lesions progress, endodontic involvement can occur.

- Based on the published literature “endodontic lesions” should be added to the list of possible oral complications of DM. It is important to emphasize that acute infections anywhere in the body can adversely affect metabolic control in person with DM, and should be treated promptly.

Legends for Figures:

Figure 1. Radiograph demonstrating extensive caries of the distal half of the maxillary second bicuspid and mesial half of the maxillary first molar. Apical periodontitis is clearly visible for the second bicuspid and widening of the apical area of the roots of the first molar is suggested. Radiograph courtesy of Drs. Y. Berlin-Brenner and L. Levin.

Figure 2. Radiograph of a maxillary first molar demonstrating a combined endodontic-periodontal lesion. Following endodontic treatment, there is widening of the apical area of the palatal root. A gutta-percha point introduced into the gingival sulcus from the buccal surface extends to the root apex. Radiograph courtesy of Drs. Y. Berlin-Brenner and L. Levin.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

References

- 1.Dominy SS, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv. 2019;5(1):eaau3333 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30746447.

- 2.Sadrameli M, et al. Linking mechanisms of periodontitis to Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020;33(2):230-8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32097126.

- 3.Borsa L, et al. Analysis the link between periodontal diseases and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34501899.

- 4.Costa MJF, et al. Relationship of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of pre-clinical studies. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(3):797-806 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33469718.

- 5.Munoz Fernandez SS, Lima Ribeiro SM. Nutrition and Alzheimer disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(4):677-97 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30336995.

- 6.Aquilani R, et al. Is the Brain Undernourished in Alzheimer’s Disease? Nutrients. 2022;14(9) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35565839.

- 7.Fukushima-Nakayama Y, et al. Reduced mastication impairs memory function. J Dent Res. 2017;96(9):1058-66 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28621563.

- 8.Kim HB, et al. Abeta accumulation in vmo contributes to masticatory dysfunction in 5XFAD Mice. J Dent Res. 2021;100(9):960-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33719684.

- 9.Miura H, et al. Relationship between cognitive function and mastication in elderly females. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30(8):808-11 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12880404.

- 10.Lexomboon D, et al. Chewing ability and tooth loss: association with cognitive impairment in an elderly population study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1951-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23035667.

- 11.Elsig F, et al. Tooth loss, chewing efficiency and cognitive impairment in geriatric patients. Gerodontology. 2015;32(2):149-56 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24128078.

- 12.Kim EK, et al. Relationship between chewing ability and cognitive impairment in the rural elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;70:209-13 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28214402.

- 13.Kim MS, et al. The association between mastication and mild cognitive impairment in Korean adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(23):e20653 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32502052.

- 14.Cardoso MG, et al. Relationship between functional masticatory units and cognitive impairment in elderly persons. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(5):417-23 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30614023.

- 15.Popovac A, et al. Oral health status and nutritional habits as predictors for developing alzheimer’s disease. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(5):448-54 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34348313.

- 16.Park T, et al. More teeth and posterior balanced occlusion are a key determinant for cognitive function in the elderly. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33669490.

- 17.Lin CS, et al. Association between tooth loss and gray matter volume in cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14(2):396-407 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32170642.

- 18.Kumar S, et al. Oral health status and treatment need in geriatric patients with different degrees of cognitive impairment and dementia: a cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(6):2171-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34322409.

- 19.Delwel S, et al. Chewing efficiency, global cognitive functioning, and dentition: A cross-sectional observational study in older people with mild cognitive impairment or mild to moderate dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:225 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33033478.

- 20.Da Silva JD, et al. Association between cognitive health and masticatory conditions: a descriptive study of the national database of the universal healthcare system in Japan. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13(6):7943-52 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33739304.

- 21.Galindo-Moreno P, et al. The impact of tooth loss on cognitive function. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26(4):3493-500 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34881401.

- 22.Stewart R, et al. Adverse oral health and cognitive decline: The health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):177-84 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23405916.

- 23.Dintica CS, et al. The relation of poor mastication with cognition and dementia risk: A population-based longitudinal study. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(9):8536-48 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32353829.

- 24.Kim MS, Han DH. Does reduced chewing ability efficiency influence cognitive function? Results of a 10-year national cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(25):e29270 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35758356.

- 25.Ko KA, et al. The Impact of Masticatory Function on Cognitive Impairment in Older Patients: A Population-Based Matched Case-Control Study. Yonsei Med J. 2022;63(8):783-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35914761.

- 26.Garre-Olmo J. [Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias]. Rev Neurol. 2018;66(11):377-86 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29790571.

- 27.Stephan BCM, et al. Secular Trends in Dementia Prevalence and Incidence Worldwide: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(2):653-80 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30347617.

- 28.Lopez OL, Kuller LH. Epidemiology of aging and associated cognitive disorders: Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;167:139-48 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31753130.

- 29.Ono Y, et al. Occlusion and brain function: mastication as a prevention of cognitive dysfunction. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(8):624-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20236235.

- 30.Kubo KY, et al. Masticatory function and cognitive function. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2010;87(3):135-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21174943.

- 31.Chen H, et al. Chewing Maintains Hippocampus-Dependent Cognitive Function. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12(6):502-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26078711.

- 32.Azuma K, et al. Association between Mastication, the Hippocampus, and the HPA Axis: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(8) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28771175.

- 33.Chuhuaicura P, et al. Mastication as a protective factor of the cognitive decline in adults: A qualitative systematic review. Int Dent J. 2019;69(5):334-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31140598.

- 34.Lopez-Chaichio L, et al. Oral health and healthy chewing for healthy cognitive ageing: A comprehensive narrative review. Gerodontology. 2021;38(2):126-35 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33179281.

- 35.Tada A, Miura H. Association between mastication and cognitive status: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;70:44-53 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28042986.

- 36.Ahmed SE, et al. Influence of Dental Prostheses on Cognitive Functioning in Elderly Population: A Systematic Review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2021;13(Suppl 1):S788-S94 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34447202.

- 37.Tonsekar PP, et al. Periodontal disease, tooth loss and dementia: Is there a link? A systematic review. Gerodontology. 2017;34(2):151-63 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28168759.

- 38.Nangle MR, Manchery N. Can chronic oral inflammation and masticatory dysfunction contribute to cognitive impairment? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2020;33(2):156-62 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31895157.

- 39.Nakamura T, et al. Oral dysfunctions and cognitive impairment/dementia. J Neurosci Res. 2021;99(2):518-28 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33164225.

- 40.Weijenberg RAF, et al. Mind your teeth-The relationship between mastication and cognition. Gerodontology. 2019;36(1):2-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30480331.

- 41.Asher S, et al. Periodontal health, cognitive decline, and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(9):2695-709 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36073186.

- 42.Lin CS. Revisiting the link between cognitive decline and masticatory dysfunction. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29304748.

- 43.Wu YT, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time – current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(6):327-39 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28497805.

- 44.Desai M, Park T. Deprescribing practices in Canada: A scoping review. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2022;155(5):249-57. doi: 10.1177/17151635221114114.

- 45.Kakkar M, Barmak AB, Arany S. Anticholinergic medication and dental caries status in middle-aged xerostomia patients-a retrospective study. J Dent Sci 2022;17(3):1206-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.12.014.

- 46.Kaur M, Himadi E, Chi DL. Prevalence of xerostomia in an adolescent inpatient psychiatric clinic: a preliminary study. Special Care Dent 2016;36:60-5.

- 47.Okamoto A, Miyachi H, Tanaka K et al. Relationship between xerostomia and psychotropic drugs in patients with schizophrenia: evaluation using an oral moisture meter. J Clin Pharm Ther 2016;41(6):684-8. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12449.

- 48.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

- 49.Loo CY, Graham RM, Hughes CV. The caries experience and behavior of dental patients with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Dent Assoc 2008;139(11):1518-24.

- 50.Allison KH, Hammond MEH, Dowsett M et al. Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Testing in Breast Cancer: ASCO/CAP Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2020 38:12, 1346-66. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.19.02309.

- 51.Feinstein JA, Feudtner C, Kempe A, Orth LE. Anticholinergic Medications and Parent-Reported Anticholinergic Symptoms in Neurologically Impaired Children. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022:S0885-3924(22)00952-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.10.013.

- 52.Ikram M, Shaikh NF, Sambamoorthi U. A Linear Decomposition Approach to Explain Excess Direct Healthcare Expenditures Associated with Pain Among Adults with Osteoarthritis. Health Serv Insights 2022;15:11786329221133957. doi: 10.1177/11786329221133957.

- 53.Bevilacqua KG, Brinkley C, McGowan J et al. “We are Getting Those Old People Things.” Polypharmacy Management and Medication Adherence Among Adult HIV Patients with Multiple Comorbidities: A Qualitative Study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2022;16:2773-80. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S382005.

- 54.Chertcoff A, Ng HS, Zhu F et al. Polypharmacy and multiple sclerosis: A population-based study. Mult Scler 2022:13524585221122207. doi: 10.1177/13524585221122207.

- 55.Aguglia A, Natale A, Fusar-Poli L et al. Complex polypharmacy in bipolar disorder: Results from a real-world inpatient psychiatric unit. Psychiatry Res 2022;318:114927. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114927.

- 56.Cheng JJ, Azizoddin AM, Maranzano MJ et al. Polypharmacy in Oncology. Clin Geriatr Med 2022;38(4):705-14. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2022.05.010.

- 57.Betts AC, Murphy CC, Shay LA et al. Polypharmacy and medication fill nonadherence in a population-based sample of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors, 2008-2017. J Cancer Surviv 2022 Nov 8. doi: 10.1007/s11764-022-01274-0.

- 58.Macrotrends. U.S. Life Expectancy 1950-2023. https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/USA/united-states/life-expectancy.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Ira-Lamster-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2020/09/edodontic-medicine-2.jpg)