Helicobacter pylori, the Oral Cavity and Gastric Diseases

The role of infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in relation to human disease represents an example of how our basic understanding of the cause of disease can change over time. Stomach and peptic ulcers were related primarily to intense stress, but in the 1980’s these concepts changed with the identification of H. pylori infection as the major cause of these disorders. This discovery, by Australians Barry Marshall and Robin Warren1Konturek SJ, Konturek PC, Konturek JW, et al. Helicobacter pylori and its involvement in gastritis and peptic ulcer formation. J Physiol Pharmacol 2006;57 Suppl 3:29-50.,2Graham DY. History of Helicobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:5191-5204., ultimately led to their receiving the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2005.

Considerable research followed the discovery that this bacterium was associated with gastric inflammation (gastritis) and peptic ulcers. Current understanding of pathology associated with H. pylori suggests that clinical disease requires both infection with the organism possessing virulence factors and a susceptible host that responds by developing an intense inflammatory response3Javed S, Skoog EC, Solnick JV. Impact of Helicobacter pylori virulence factors on the host immune response and gastric pathology. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2019;421:21-52.. Among the interesting aspects of H. pylori infection is the potential role of the dental biofilm as a reservoir for H. pylori, and the role of H. pylori in oral diseases.

H. pylori is a now recognized to be a widely distributed microorganism that is responsible for a variety of upper gastrointestinal disorders, including gastritis, gastric ulcers, and certain cancers of the stomach including adenocarcinoma. A review of the epidemiology of H. pylori across the globe reveals widespread distribution of the organism, as well as identification of risk factors for infection4Sjomina O, Pavlova J, Niv Y, Leja M. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2018;23 Suppl 1:e12514..

- The general trend across the globe is for decreasing prevalence of infection with H. pylori, but in some regions (i.e. the Middle East), prevalence has not changed.

- Africa has the highest prevalence (79.1%) and Oceania the lowest (24.4%). The annual recurrence rate was estimated to be 4.3%.

- Higher prevalence of infection is associated with lower income, poor diet (fewer fruits and vegetables), poor hygiene and contaminated water.

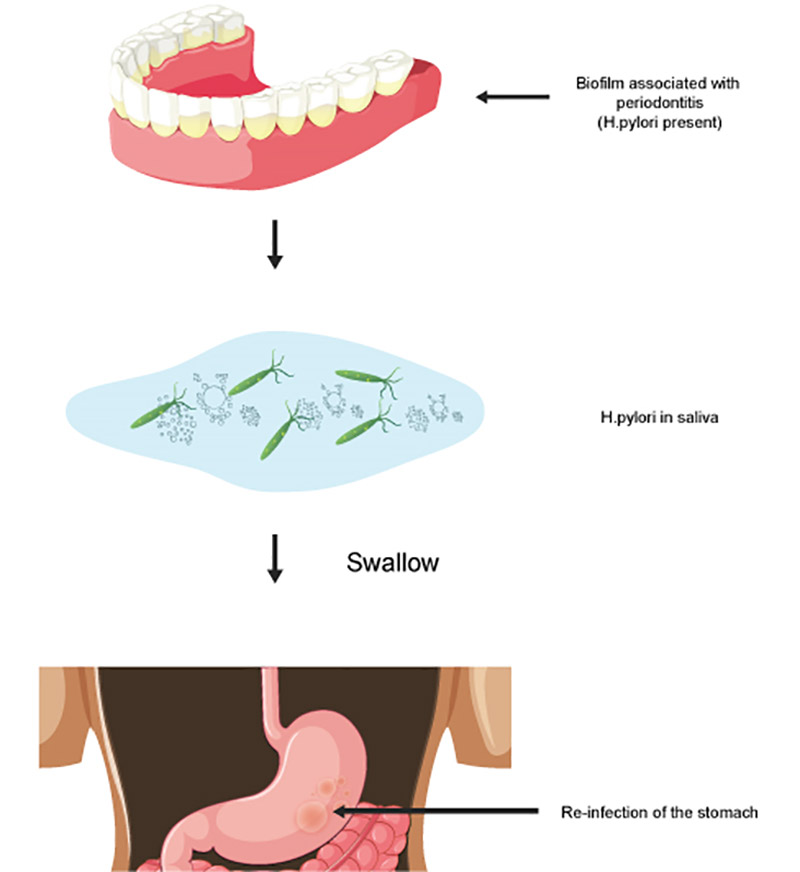

H. pylori has been identified in the oral cavity, been examined for its presence in the dental plaque and saliva as a reservoir for infection/re-infection of the stomach, as well as its potential role in the pathogenesis of a number of oral diseases and disorders. These include recurrent aphthous stomatitis and periodontal disease, as well as squamous cell carcinoma, burning mouth syndrome and halitosis 5Adler I, Muino A, Aguas S, et al. Helicobacter pylori and oral pathology: relationship with the gastric infection. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:9922-9935.. This review concluded that the oral cavity is an important extra-gastric source of H. pylori, and that following treatment of H. pylori in the stomach, the oral cavity can be a source of re-infection of that organ.

Upon evaluating the role of H. pylori in specific oral/dental disorders, it was concluded that this organism has a role in the etiology of aphthous ulcers, perhaps mediated by anemia, which itself can be related to a bleeding gastric ulcer. Antibiotic treatment to eliminate H. pylori resulted in a decrease in aphthous ulcers. For periodontal disease, the majority of studies (6 of 7) that used molecular techniques (PCR) to examine the presence of H. pylori in periodontal disease-associated biofilm have identified this organism in the oral cavity. The organism was found in the supragingival biofilm, the subgingival biofilm and in the saliva, but not on the tongue. Further, pharmacological (triple therapy) treatment of gastric H. pylori infection was more effective in elimination of gastric infection as compared to eradication of the organism from the oral cavity.

The relationship of H. pylori infection and squamous cell cancer has been examined, and no association was found. The association between H. pylori infection and halitosis has been studied and preliminary data suggest an association, but this work remains incomplete. Further, this review identified an association of H. pylori infection, symptoms of burning mouth and hyperplasia of the dorsum of the tongue. Additional research is needed to clarify this proposed syndrome.

Since the review5Adler I, Muino A, Aguas S, et al. Helicobacter pylori and oral pathology: relationship with the gastric infection. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:9922-9935. was published in 2014, additional research has helped clarify the relationships of H. pylori to oral disease, and as a reservoir for re-infection of the stomach. A particular focus has been on the presence of H. pylori as a component of the biofilm associated with periodontitis. This association can be examined from three perspectives:

- Is there an association of H. pylori in the oral cavity (biofilm, saliva) and gastric disease?

- Is there an association of H. pylori and periodontitis?

- If there is an association, is this modified by treatment?

The evaluation of H. pylori in the oral cavity can be accomplished using a variety of approaches. A saliva test for oral H. pylori infection offers obvious advantages. A study of more than 4000 persons examined the prevalence of H. pylori in saliva with an immunologic assay based on the detection of the organism with a monoclonal antibody6Yu Y, Zhao L, Wang S, Yee JK. Helicobacter pylori – specific antigen yests in saliva to identify an oral infection. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2017;47:323-327.. In addition, they used a urea breath test to assess H. pylori in the stomach. Four groups of adults were analyzed: <45 years (group A), 45-59 years (group B), 60-74 years (group C) and 75-89 years (group D). There was an inverse relationship of age and detection of H. pylori in saliva, with rates of 60%, 49%, 42% and 25% for groups A to D. For the detection of gastric H. pylori, no differences were seen for groups A, B and C, but group D demonstrated a lower percentage of positive individuals.

Several studies have suggested a possible role for H. pylori in the etiology of periodontitis. A meta-analysis that examined the relationship of H. pylori and periodontitis included 13 studies, with a total of 6800 patients7Chen Z, Cai J, Chen YM, et al. A meta-analysis of the association between the presence of Helicobacter pylori and periodontal diseases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e15922.. The summary revealed that the odds ratio of the association between oral H. pylori infection and periodontal diseases (gingivitis or periodontitis), which included 13 studies, was 2.31. The odd ratio for stomach H. pylori infection and periodontal disease, which only included 2 studies, was 2.90.

They summarized their findings as:

- There is an association between H. pylori infection in the mouth and infection in the stomach. They emphasized that anatomically the oral cavity is the first bacterial reservoir for H. pylori. The data indicated that co-infection between the oral cavity and stomach was about 50%.

- H. pylori is present in the periodontitis-associated biofilm, and therefore may also be a periodontal pathogen.

The authors note limitations of their review, including the cross-sectional nature of the studies (which precludes establishing cause and effect), the multi-factorial nature of periodontal disease (and that many of the included studies did not control for potential confounders) and that the studies did not consider the presence of established periodontal pathogens.

A relatively large study of the effect of H. pylori infection on periodontitis examined the relationship of infection and periodontitis as identified by salivary levels of biomarkers for periodontal tissue destruction and bleeding8Adachi K, Notsu T, Mishiro T, Yoshikawa H, Kinoshita Y. Influence of Helicobacter pylori infection on periodontitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;34:120-123.. The results indicated a positive association between the biochemical tests for periodontitis and infection with H. pylori, and this association was reduced after patients with H. pylori infection received eradication therapy for the stomach infection.

An important consideration in these studies is the effect of treatment on the periodontitis-H. pylori-gastric disease relationship. A study of the effect of eradication therapy for gastric H. pylori infection indicated that after H. pylori was eliminated from the stomach, recurrence of gastric infection was reduced if periodontal therapy was also provided9Tongtawee T, Wattanawongdon W, Simawaranon T. Effects of periodontal therapy on eradication and recurrence of Helicobacter pylori infection after successful treatment. J Int Med Res 2019;47:875-883.. A close association of salivary H. pylori and gastric H. pylori was observed. This finding is supported by other research10Azzi L, Carinci F, Gabaglio S, et al. Helicobacter pylori in periodontal pockets and saliva: a possible role in gastric infection relapses. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2017;31:257-262.. A case report described a patient who had H. pylori infection of the stomach, and gastric symptoms, as well as H. pylori infection of the oral cavity. The patient received triple therapy and eradication of H. pylori from both the stomach and oral cavity was achieved11Kadota T, Ogaya Y, Hatakeyama R, Nomura R, Nakano K. Comparison of oral flora before and after triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in patient with gastric disease. Odontology 2019;107:261-267..

Treatment of H. pylori infection of the stomach is based on the use of both antibiotics to eliminate the organism and other drugs to decrease production of stomach acid. In the past, infection was treated with a 7-day regimen including the antibiotics amoxicillin and clarithromycin with a proton pump inhibitor to reduce acid production (the so-called triple therapy). However, with strains of H. pylori resistant to the antibiotics metronidazole and clarithromycin on the rise, new approaches to eradication are being examined to eradicate the organism 12Suzuki S, Esaki M, Kusano C, Ikehara H, Gotoda T. Development of Helicobacter pylori treatment: How do we manage antimicrobial resistance? World J Gastroenterol 2019;25:1907-1912.,13Urgesi R, Cianci R, Riccioni ME. Update on triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: current status of the art. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2012;5:151-157. (see Table 1).

Different strains of H. pylori have been identified, with different genes accounting for variable pathogenicity. A study of the H. pylori genotypes in the oral cavity and stomach revealed concordance in nearly 40% of patients14Medina ML, Medina MG, Merino LA. Correlation between virulence markers of Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity and gastric biopsies. Arq Gastroenterol 2017;54:217-221.. Furthermore, H. pylori infection was found in the mouths of more than 75% of pre-school children, and was higher in children where parents were identified with H. pylori infection of the stomach15Xu Y, Song Y, Wang X, Gao X, Li S, Yee JK. A clinical trial on oral H. pylori infection of preschool children. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2018;48:751-756..

In summary, there appears to be a relationship between H. pylori infection of the oral cavity and stomach, and that the biofilm in the oral cavity can serve as a reservoir for infection/re-infection of the stomach with the organism (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the reservoir concept appears to be more of a concern in persons with periodontitis, though not all studies have observed this association16Alagl AS, Abdelsalam M, El Tantawi M, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori gastritis and dental diseases: A cross-sectional, hospital-based study in Eastern Saudi Arabia. J Periodontol 2019;90:375-380.,17Ansari SA, Iqbal MUN, Khan TA, Kazmi SU. Association of oral Helicobacter pylori with gastric complications. Life Sci 2018;205:125-130..

H. pylori is a ubiquitous microorganism, and the oral cavity is not the only source of infection; both contaminated water and food have been implicated in infection18Quaglia NC, Dambrosio A. Helicobacter pylori: A foodborne pathogen? World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:3472-3487.. However, comprehensive treatment of patients with gastric infection should include an evaluation for the presence of periodontitis, especially if infection returns after treatment to eliminate the organism in the stomach. While there is much to be learned about the role of oral H. pylori in infection and clinical diseases of the stomach, the consequences of persistent infection, including both gastric ulcers and stomach cancer, and the effect of these disorders on quality of life, make this a topic of interest to oral health care providers.

Table 1: A variety of treatment approach for H. pylori infection have been used. These involve a combination of acid reduction (proton pump inhibitors) and antibiotics. Due to increased antimicrobial resistance, there are various approaches to treating H. pylori infection of the gastrointestinal track.

| Therapy | Acid Reduction | Antibiotics | Duration | Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concomitant quadruple therapy | E L O P R |

A C M or TN |

5-14 | 83% |

| Standard triple therapy | E L P R |

A C |

7, 14 | 73%, 81% |

| High dose dual therapy | E O R |

A | 14 | 86% |

| Vonoprazan triple therapy | V | A | 7 | 86% |

| Vonoprazan triple therapy | V | A | 7 | 94% |

Abbreviations: acid reduction

E = esomeprazole

O = omeprazole

L = lansoprazole

P = pantoprazole

R = rabeprazole

V = vonoprazan

Abbreviations: antibiotics

T = tetracycline

M = metronidazole

A = amoxicillin

C = clarithromycin

TN = tinidazole

Adapted from Suzuki et al 2017 (reference #12). For specific dosages of each medication see the original paper.

References

- 1.Marui VC, Souto MLS, Rovai ES, Romito GA, Chambrone L, Pannuti CM. Efficacy of preprocedural mouthrinses in the reduction of microorganisms in aerosol: A systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2019;150(12):1015-26.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2019.06.024.

- 2.Sreenivasan PK, Gittins E. The effects of a chlorhexidine mouthrinse on culturable micro-organisms of the tongue and saliva. Microbiol Res 2004;159(4):365-70.

- 3.Larsen PE. The effect of a chlorhexidine rinse on the incidence of alveolar osteitis following the surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991;49(9):932-37.

- 4.Hennessy B, Joyce A. A survey of preprocedural antiseptic mouth rinse use in Army dental clinics. Mil Med 2004;169(8):600-3.

- 5.American Dental Association. Interim Guidance for Minimizing Risk of COVID-19 Transmission. Available at: https://www.ada.org/~/media/CPS/Files/COVID/ADA_COVID_Int_Guidance_Treat_Pts.pdf.

- 6.Meng L, Fang H, Bian Z.. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and Future Challenges for Dental and Oral Medicine. J Dent Res 2020;99. 002203452091424. 10.1177/0022034520914246.

- 7.Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci 2020;12:9.

- 8.Kobza J, Pastuszka JS, Brągoszewska E. Do exposures to aerosols pose a risk to dental professionals? Occupat Med 2018;68(7):454-8.

- 9.Tellier, Li Y, Cowling BJ, Tang JW. Recognition of aerosol transmission of infectious agents: a commentary. BMC Infect Dis 2019;19:101. Available at: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-019-3707-y.

- 10.Grenier D. Quantitative analysis of bacterial aerosols in two different dental clinic environments. Appl Environ Microbiol 1995;61(8):3165-8.

- 11.Al Maghlouth A, Al Yousef Y, Al Bagieh N. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of bacterial aerosols. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2004 Nov 15;5(4):91-100.

- 12.Feres M, Figueiredo LC, Faveri M, Stewart B, de Vizio W. The effectiveness of a preprocedural mouthrinse containing cetylpyridinium chloride in reducing bacteria in the dental office. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141:415-22.

- 13.Domingo MA, Farrales MS, Loya RM, Pura MA, Uy H. The effect of 1% povidone-iodine as a pre-procedural mouthrinse in 20 patients with varying degrees of oral hygiene. J Philipp Dent Assoc 1996;48(2):31-8.

- 14.DePaola LG, Eshenaur Spolarich A. Safety and Efficacy of Antimicrobial Mouthrinses in Clinical Practice. J Dent Hyg 2007;81(suppl 1) 117. Available at: https://jdh.adha.org/content/jdenthyg/81/suppl_1/117.full.pdf.

- 15.Scheie AA. Modes of action of currently known chemical antiplaque agents other than chlorhexidine. J Dent Res 1989;68 (Spec Iss):1609-16.

- 16.Nazzaro F, Fratianni F, De Martino L, Coppola R, De Feo V. Effect of essential oils on pathogenic bacteria. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2013;6(12):1451‐74. doi:10.3390/ph6121451.

- 17.Prescribers Digital Reference. povidone iodine – Drug Summary. Available at: https://www.pdr.net/drug-summary/Betadine-5–povidone-iodine-2152.

- 18.Litsky BY, Mascis JD, Litsky W. Use of an antimicrobial mouthwash to minimize the bacterial aerosol contamination generated by the high-speed drill. PlumX Metrics. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(70)90407-X.

- 19.Wyler D, Miller RL, Micik RE. Efficacy of self-administered preoperative oral hygiene procedures in reducing the concentration of bacteria in aerosols generated during dental procedures. J Dent Res 1971;50(2):509.

- 20.Logothetis DD, Martinez-Welles JM. Reducing bacterial aerosol contamination with a chlorhexidine gluconate pre-rinse. J Am Dent Assoc 1995;126(12):1634-9.

- 21.Klyn SL, Cummings DE, Richardson BW, Davis RD. Reduction of bacteria-containing spray produced during ultrasonic scaling. Gen Dent 2001;49(6):648-52.

- 22.Fine DH, Mendieta C, Barnett ML, Furgang D, Meyers R. Efficacy of preprocedural rinsing with an antiseptic in reducing viable bacteria in dental aerosols. J Periodontol 1992;63(10):821-4.

- 23.Fine DH, Furgang D, Korik I, Olshan A, Barnett ML, Vincent JW. Reduction of viable bacteria in dental aerosols by preprocedural rinsing with an antiseptic mouthrinse. Am J Dent 1993;6(5):219-21.

- 24.Altonen M, Saxen L, Kosunen T, Ainamo J. Effect of two antimicrobial rinses and oral prophylaxis on preoperative degerming of saliva. Int J Oral Surg 1976;5(6):276-84.

- 25.Veksler AE, Kayrouz GA, Newman MG. Reduction of salivary bacteria by pre-procedural rinses with chlorhexidine 0.12%. J Periodontol 1991;62(11):649-51.

- 26.Balbuena L, Stambaugh KI, Ramirez SG, Yeager C. Effects of topical oral antiseptic rinses on bacterial counts of saliva in healthy human subjects. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;118(5):625-9.

- 27.Kirk-Bailey J, Combes J, Sunkaraneni S, Challacombe S. The use of Povidone Iodine nasal spray and mouthwash during the current COVID-19 pandemic for the reduction of cross infection and protection of healthcare workers. Last revised 24 April 2020. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3563092.

- 28.To KK-W, Tsang OT-Y, Yip C-YC, Chan K-H, Wu T-C, Chan JM-C, et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2020;361:1319. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa149.

- 29.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1177-9.

- 30.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020. Available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2004973.

- 31.Guo Z-D, Wang Z-Y, Zhang S-F, Li X, Li L, Li C, et al. Aerosol and surface distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in hospital wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis 2020 Jul [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.200885.

- 32.Caruso AA, Del Prete A, Lazzarino AI, Capaldi R, Grumetto L. May hydrogen peroxide reduce the hospitalization rate and complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection? Letter to the Editor. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology as part of the Cambridge Coronavirus Collection. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.170.

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chemical Disinfectants

Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities (2008). Available at:

https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/disinfection/disinfection-methods/chemical.html#Hydrogen. - 34.Eggers, M. Infectious Disease Management and Control with Povidone Iodine. Infect Dis Ther 2019;8:581-93.

- 35.Kanagalingam J, Feliciano R, Hah JH, Labib H, Le TA, Lin JC. Practical use of povidone-iodine antiseptic in the maintenance of oral health and in the prevention and treatment of common oropharyngeal infections. Int J Clin Pract 2015;69(11):1247-56. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12707.

- 36.Yeh YT, Chiu YT, Liu CT, Wu SJ, Lee TI. Development and evaluation of an integrated patient-oriented education management system for diabetes. Stud Health Technol Inform 2006;122:172-5.

- 37.Wong HM, Bridges SM, McGrath CP, Yiu CKY, Zayts OA, Au TKF. Impact of prominent themes in clinician-patient conversations on caregiver’s perceived quality of communication with paediatric dental visits. PLoS ONE 2017;12(1):e0169059.

- 38.Misra S, Daly B, Dunne S, Millar B, Packer M, Asimakopoulou K. Dentist–patient communication: what do patients and dentists remember following a consultation? Implications for patient compliance. Patient Preference and Adherence 2013:7:543-9.

- 39.Blinder D, Rotenberg L, Peleg M, Taicher S. Patient compliance to instructions after oral surgical procedures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001;30(3):216-9.

- 40.Tiffany B, Blasi P, Catz SL, McClure JB. Mobile apps for oral health promotion: Content review and heuristic usability analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e11432.

- 41.Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation standards for dental education programs. Chicago: 2010.

- 42.Mull, Carrie, “Implementation of a Patient-Centered Communication Model in the Emergency Department” (2017). Doctoral Projects. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/kcon_doctoralprojects/46

- 43.Alvarez S, Schultz J-H. A communication-focused curriculum for dental students – an experiential training approach. BMC Medical Education 2018;18:55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1174-6

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Ira-Lamster-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2019/09/Helicobacter-pylori-the-Oral-Cavity-and-Gastric-Diseases-2.jpg)