Oral Health and Alzheimers Disease Part 1: Oral Infection and Alzheimer’s Disease

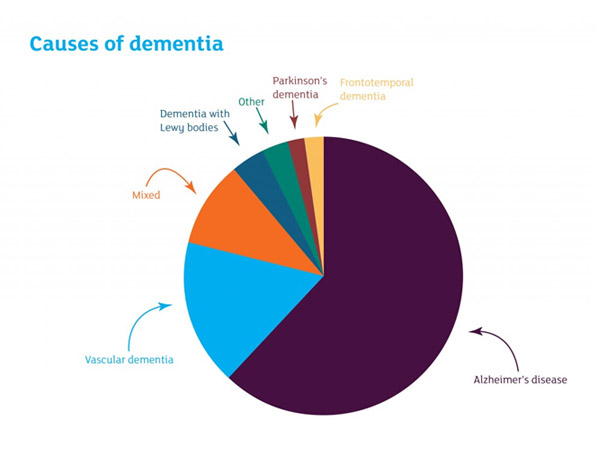

The relationship of oral infection and oral inflammation to certain non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs) has emphasized the importance of the mouth to the body and illustrates how the health of the oral cavity can impact general health. Specific relationships have been identified for oral infection/oral inflammation and certain systemic diseases and conditions, primarily cardiovascular/cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy outcomes and respiratory diseases. Another association that has received a great deal of interest is the relationship of oral infection and cognitive impairment, specifically the type of dementia known as Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Figure 1).

The relationship of oral disease to AD has two broad components: potential mechanisms that define how oral infection can impact the onset and progression of AD, and how AD impacts oral health and the challenge of providing dental care to persons with AD.

There is overwhelming clinical evidence that an association exists between the presence of periodontitis and cognitive decline. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported a bidirectional association between dementia and periodontal disease1Kapellas K, Ju X, Wang X, Mueller N, Jamieson LM. The association between periodontal disease and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent Oral Biol Craniofacial Res; doi:10.31487/j.DOBCR.2019.01.005.. The review selected 12 publications that met the criteria. Eight papers reported the effect of dementia on periodontal disease, and 4 papers reported on the effect of periodontal disease on dementia. The meta-analysis indicated a 17% greater chance of having dementia if periodontal disease was present (odds ratio= 1.17, CI = 1.02-1.34). Furthermore, there was a 69% greater chance of having periodontal disease if dementia was present (odds ratio= 1.69; CI=1.23-2.30). In addition, a longitudinal evaluation of older adults (ranging in age from 60 to 96 years) over a period of 6 years revealed that a decline in cognitive function was associated with a number of risk factors2Nilsson H, Sanmartin Berglund J, Renvert S. Longitudinal evaluation of periodontitis and development of cognitive decline among older adults. J Clin Periodontol 2018;45:1142-1149.. These were being in an old age category, having only an elementary school education (limited education), living alone, a history of heart disease and low weight (BMI <25). In terms of dental variables, risk factors were being edentulous, having a reduced number of teeth (1-19), and demonstrating loss of alveolar bone of at least 4mm at 30% or more of recorded sites.

A number of review papers have speculated on the mechanistic relationship of periodontal disease and AD. Teixeira and co-workers3Teixeira FB, Saito MT, Matheus FC, et al. Periodontitis and Alzheimer’s Disease: A possible comorbidity between oral chronic inflammatory condition and neuroinflammation. Front Aging Neurosci 2017;9:327. indicated that the logical linkage is through inflammation. The pathogenesis of AD has been associated with systemic inflammation that affects inflammation in the brain, with an impact on microglia cells, which are resident macrophage-like inflammatory cells that comprise up 10% of the cells in the brain4Cunningham C, Hennessy E. Co-morbidity and systemic inflammation as drivers of cognitive decline: New experimental models adopting a broader paradigm in dementia research. Alzheimers Res Ther 2015;7:33.. Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory condition that can exist for many years, which has been shown to contribute to the systemic inflammatory burden5Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2015;15:30-44..

Periodontitis can lead to an increase in certain pro-inflammatory mediators in the serum (including interleukin-1, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α), which could be the link6Gaur S, Agnihotri R. Alzheimer’s disease and chronic periodontitis: Is there an association? Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015;15:391-404.. Silvestre and colleagues7Silvestre FJ, Lauritano D, Carinci F, Silvestre-Rangil J, Martinez-Herrera M, Del Olmo A. Neuroinflammation, Alzheimers disease and periodontal disease: Is there an association between the two processes? J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2017;31:189-196. suggested that both the presence of inflammatory mediators, which would be elevated in the circulation as a result of periodontitis, and periodontal pathogens that gain access to the systemic circulation, could both be contributing factors. They also noted that both disorders have increased prevalence with advancing age. A recent review8Pazos P, Leira Y, Dominguez C, Pias-Peleteiro JM, Blanco J, Aldrey JM. Association between periodontal disease and dementia: a literature review. Neurologia 2018;33:602-613. came to similar conclusions, but stated that both causality and the ultimate strength of this relationship were not known.

A review that examined the potential importance of infections, including oral infections, to the pathogenesis of AD noted that a number of oral microorganisms, including bacteria [spirochetes and other anaerobic bacteria associated with periodontitis such as Porphyromonas gingivalis (PG)], viruses (Herpes simplex type 1) and fungi (Candida) have been implicated. Direct infection of the brain would trigger an inflammatory response9Olsen I, Singhrao SK. Can oral infection be a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease? J Oral Microbiol 2015;7:29143.. They concluded that oral infection is likely a risk factor for AD, and should be considered along with genetic predisposition, nutritional deficiencies and the presence of other chronic diseases. Further, proper oral hygiene and treatment of periodontal diseases would represent an approach to modifying the risk for AD.

A recent report in Science Advances by Dominy and colleagues10Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv 2019;5:eaau3333. has made an important contribution to understanding of the pathogenesis of AD as related to periodontal disease. This comprehensive report studied persons with AD, as well as an animal model to specifically dissect molecular aspects of AD (Table 1). In both parts of this research, the focus was on PG, which is a key microorganism in human periodontitis. PG is a Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium that has been shown to produce a range of virulence factors that account for its role in periodontitis11Mysak J, Podzimek S, Sommerova P, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis: Major periodontopathic pathogen overview. J Immunol Res 2014;2014:476068..

In the first series of studies, they evaluated post-mortem brain tissue from patients with AD, as well as tissue from control brains from patients who did not have evidence of cognitive impairment. Further, cerebrospinal fluid and saliva were obtained from patients who had been diagnosed with AD.

Evaluation of the post-mortem brain tissue revealed that better than 90% of samples stained positively for PG gingipains, which are a group of proteases that have a role in the pathogenicity of PG by aiding in the colonization of the bacteria, neutralizing the host response to infection as well as promoting host tissue breakdown. In contrast, the brain tissue from unaffected persons demonstrated significantly lower levels of gingipains. The investigations also evaluated the levels of tau, a protein found in neurons, which is dramatically increased in persons with AD. A correlation was observed between increased gingipains and increased tau in the AD brains. Similar results were seen for another marker of AD known as ubiquitin. An anatomical analysis indicated that the gingipains were observed in the hippocampus, the region of the brain that is among the first to be affected by AD. Gingipains were also identified in the cerebral cortex. Of interest, the lower levels of gingipains were observed in the brain tissue from the controls, suggesting a pre-clinical continuum of pathology that could lead to development of clinical AD.

Further, these investigators evaluated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and saliva from patients with AD and mild/moderate impairment. Seven of ten AD patients demonstrated PG by polymerase chain reaction, and all 10 had this microorganism in saliva. Analysis of CSF is an accepted approach to evaluated infections of the brain. Additional studies using the postmortem brain tissue further supported the concept that PG as having a role in the development of AD.

This same report described a study in mice, which were orally-infected with PG, leading to establishment of a brain infection with this pathogen. The result of the infection in the animals was an increase in production of an important marker for AD known as Aβ1-42, which is a protein that is the major component of the amyloid plaques seen in the brain of persons with AD. After brain infection was established, the administration of novel agents that block gingipains reduced the bacterial load in the mouse brains, reduced production of Aβ1-42 and reduced inflammation in the brain. Though only tested in mice, these novel small molecular weight gingipain inhibitors offer promise for treatment of AD when associated with PG infection.

This potentially transformative study represents an important advance that provides a specific mechanism to support the conclusions and findings from previously published reviews and original research suggesting a linkage between oral disease, specifically the presence of periodontitis, and AD. Several individual studies are worth noting.

In 2007, a study was published in the Journal of the American Dental Association that reported a relationship of oral disease to dementia/Alzheimer’s disease12Stein PS, Desrosiers M, Donegan SJ, Yepes JF, Kryscio RJ. Tooth loss, dementia and neuropathology in the Nun study. J Am Dent Assoc 2007;138:1314-1322; quiz 1381-1312.. This study was part of a longitudinal evaluation of nuns, who have a defined and simple lifestyle, which is without many of the risk factors identified for chronic diseases. In this study, neuropathologic findings were available post-mortem. The data revealed an increased risk for dementia associated with fewer remaining teeth (1 to 9). The problem with this study is that tooth loss could be due to periodontal disease as well as caries or other causes. Nevertheless, this report generated a great deal of interest in the association of dementia/AD and poor oral health. Additional epidemiological evidence of an association between poor oral health and AD is provided by a national database from Taiwan13Chen CK, Wu YT, Chang YC. Association between chronic periodontitis and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A retrospective, population-based, matched-cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther 2017;9:56.. Evaluating 9,291 persons with chronic periodontitis, and 18,672 persons without chronic periodontitis, but matched for a variety of variables including age and sex, they determined that the relative risk of developing AD was 1.71 if there was a 10-year history of chronic periodontitis. However, it is important to note that the patients with chronic periodontitis had other co-morbidities associated with development of AD (i.e. hyperlipidaemia, a history of traumatic brain injury).

In terms of specific periodontitis-associated variables linked to development of AD, a variety of experimental studies has suggested a role for periodontal pathogens. One study demonstrated that a culture of astrocyte cells (which serve an important support role in the brain) absorbed lipopolysaccharide from PG, and when a lysate from brains of 10 AD patients were tested, 4 of 10 lysates showed absorption. None of the lysates from control (non-affected) brains demonstrated absorption14Poole S, Singhrao SK, Kesavalu L, Curtis MA, Crean S. Determining the presence of periodontopathic virulence factors in short-term postmortem Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. J Alzheimers Dis 2013;36:665-677..

Further, elevated antibody titers to a number of periodontal bacteria (including PG) were associated with all increased risk for AD15Noble JM, Scarmeas N, Celenti RS, et al. Serum IgG antibody levels to periodontal microbiota are associated with incident Alzheimer disease. PLoS One 2014;9:e114959.. A 6-month trial examining progression of dementia in patients with AD demonstrated that while periodontitis at the initiation of the study was not related to the degree of cognitive decline, the presence of periodontitis was associated with a 6-fold increase in cognitive decline over the following 6 months. The authors related this to increased concentration of pro-inflammatory markers in serum16Ide M, Harris M, Stevens A, et al. Periodontitis and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 2016;11:e0151081..

While these earlier reviews and research studies suggested an association between chronic periodontitis and AD, and offered some potential mechanisms to explain this association, the paper by Dominy and colleagues is an important step forward because it suggests a specific mechanisms to explain this association using both human brain tissue, and an animal model, to support the importance of specific proteases released from PG. Further, the ability of small molecular weight inhibitors of these proteases to reduce the pathological effects of colonization in a mouse model not only supports this specific linkage, but may offer a treatment approach for patients with AD. For the dental clinician, the importance of preventing periodontitis, and treating this disorder if present, is a point of emphasis. These concerns are becoming increasingly important as populations age and retain teeth, and the prevalence of periodontitis increases in older individuals.

The field of dementia research continues to evolve, with changes occurring to the definition of specific disorders and diagnostic criteria, as well as the understanding of risk factors for disorders such as AD17James BD, Bennett DA. Causes and patterns of dementia: An update in the era of redefining Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Public Health 2019;40:65-84.. Dementia generally demonstrates a lengthy preclinical phase, and the natural history occurs over decades. The development of dementia/AD is the result of the indirect and direct influence of several risk factors (i.e. genetics, behavior, health status including the presence of NCDs; Figure 2). The study by Dominy and colleagues10Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv 2019;5:eaau3333. adds important information to our understanding of the risk for these debilitating disorders.

In the next essay in this series, the challenges associated with providing dental care to persons with dementia/AD will be reviewed.

Table 1. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors.

| Major Findings | |

|---|---|

| Humans |

|

| Animal Model |

|

-

Figure 1

Distribution of types of dementia. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type.

-

Figure 2

Dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, has a complex etiology. The various clinical manifestations can impact the affected person’s ability to function in many ways.

References

- 1.Dominy SS, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv. 2019;5(1):eaau3333 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30746447.

- 2.Sadrameli M, et al. Linking mechanisms of periodontitis to Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020;33(2):230-8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32097126.

- 3.Borsa L, et al. Analysis the link between periodontal diseases and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34501899.

- 4.Costa MJF, et al. Relationship of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of pre-clinical studies. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(3):797-806 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33469718.

- 5.Munoz Fernandez SS, Lima Ribeiro SM. Nutrition and Alzheimer disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(4):677-97 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30336995.

- 6.Aquilani R, et al. Is the Brain Undernourished in Alzheimer’s Disease? Nutrients. 2022;14(9) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35565839.

- 7.Fukushima-Nakayama Y, et al. Reduced mastication impairs memory function. J Dent Res. 2017;96(9):1058-66 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28621563.

- 8.Kim HB, et al. Abeta accumulation in vmo contributes to masticatory dysfunction in 5XFAD Mice. J Dent Res. 2021;100(9):960-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33719684.

- 9.Miura H, et al. Relationship between cognitive function and mastication in elderly females. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30(8):808-11 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12880404.

- 10.Lexomboon D, et al. Chewing ability and tooth loss: association with cognitive impairment in an elderly population study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1951-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23035667.

- 11.Elsig F, et al. Tooth loss, chewing efficiency and cognitive impairment in geriatric patients. Gerodontology. 2015;32(2):149-56 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24128078.

- 12.Kim EK, et al. Relationship between chewing ability and cognitive impairment in the rural elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;70:209-13 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28214402.

- 13.Kim MS, et al. The association between mastication and mild cognitive impairment in Korean adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(23):e20653 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32502052.

- 14.Cardoso MG, et al. Relationship between functional masticatory units and cognitive impairment in elderly persons. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(5):417-23 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30614023.

- 15.Popovac A, et al. Oral health status and nutritional habits as predictors for developing alzheimer’s disease. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(5):448-54 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34348313.

- 16.Park T, et al. More teeth and posterior balanced occlusion are a key determinant for cognitive function in the elderly. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33669490.

- 17.Lin CS, et al. Association between tooth loss and gray matter volume in cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14(2):396-407 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32170642.

- 18.Kumar S, et al. Oral health status and treatment need in geriatric patients with different degrees of cognitive impairment and dementia: a cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(6):2171-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34322409.

- 19.Delwel S, et al. Chewing efficiency, global cognitive functioning, and dentition: A cross-sectional observational study in older people with mild cognitive impairment or mild to moderate dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:225 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33033478.

- 20.Da Silva JD, et al. Association between cognitive health and masticatory conditions: a descriptive study of the national database of the universal healthcare system in Japan. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13(6):7943-52 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33739304.

- 21.Galindo-Moreno P, et al. The impact of tooth loss on cognitive function. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26(4):3493-500 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34881401.

- 22.Stewart R, et al. Adverse oral health and cognitive decline: The health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):177-84 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23405916.

- 23.Dintica CS, et al. The relation of poor mastication with cognition and dementia risk: A population-based longitudinal study. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(9):8536-48 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32353829.

- 24.Kim MS, Han DH. Does reduced chewing ability efficiency influence cognitive function? Results of a 10-year national cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(25):e29270 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35758356.

- 25.Ko KA, et al. The Impact of Masticatory Function on Cognitive Impairment in Older Patients: A Population-Based Matched Case-Control Study. Yonsei Med J. 2022;63(8):783-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35914761.

- 26.Garre-Olmo J. [Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias]. Rev Neurol. 2018;66(11):377-86 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29790571.

- 27.Stephan BCM, et al. Secular Trends in Dementia Prevalence and Incidence Worldwide: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(2):653-80 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30347617.

- 28.Lopez OL, Kuller LH. Epidemiology of aging and associated cognitive disorders: Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;167:139-48 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31753130.

- 29.Ono Y, et al. Occlusion and brain function: mastication as a prevention of cognitive dysfunction. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(8):624-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20236235.

- 30.Kubo KY, et al. Masticatory function and cognitive function. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2010;87(3):135-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21174943.

- 31.Chen H, et al. Chewing Maintains Hippocampus-Dependent Cognitive Function. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12(6):502-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26078711.

- 32.Azuma K, et al. Association between Mastication, the Hippocampus, and the HPA Axis: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(8) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28771175.

- 33.Chuhuaicura P, et al. Mastication as a protective factor of the cognitive decline in adults: A qualitative systematic review. Int Dent J. 2019;69(5):334-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31140598.

- 34.Lopez-Chaichio L, et al. Oral health and healthy chewing for healthy cognitive ageing: A comprehensive narrative review. Gerodontology. 2021;38(2):126-35 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33179281.

- 35.Tada A, Miura H. Association between mastication and cognitive status: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;70:44-53 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28042986.

- 36.Ahmed SE, et al. Influence of Dental Prostheses on Cognitive Functioning in Elderly Population: A Systematic Review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2021;13(Suppl 1):S788-S94 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34447202.

- 37.Tonsekar PP, et al. Periodontal disease, tooth loss and dementia: Is there a link? A systematic review. Gerodontology. 2017;34(2):151-63 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28168759.

- 38.Nangle MR, Manchery N. Can chronic oral inflammation and masticatory dysfunction contribute to cognitive impairment? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2020;33(2):156-62 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31895157.

- 39.Nakamura T, et al. Oral dysfunctions and cognitive impairment/dementia. J Neurosci Res. 2021;99(2):518-28 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33164225.

- 40.Weijenberg RAF, et al. Mind your teeth-The relationship between mastication and cognition. Gerodontology. 2019;36(1):2-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30480331.

- 41.Asher S, et al. Periodontal health, cognitive decline, and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(9):2695-709 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36073186.

- 42.Lin CS. Revisiting the link between cognitive decline and masticatory dysfunction. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29304748.

- 43.Wu YT, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time – current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(6):327-39 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28497805.

- 44.National Psoriasis Foundation. Soriatane (Acitretin). https://www.psoriasis.org/soriatane-acitretin/.

- 45.National Psoriasis Foundation. Current Biologics on the Market. https://www.psoriasis.org/current-biologics-on-the-market/.

- 46.Dalmády S, Kemény L, Antal M, Gyulai R. Periodontitis: a newly identified comorbidity in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2020;16(1):101-8. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1700113.

- 47.Mickenautsch S, Yengopal V. Effect of xylitol versus sorbitol: a quantitative systematic review of clinical trials. Int Dent J 2012;62(4):175-88.

- 48.Rethman MP, Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Billings RJ, Burne RA, Clark M, Donly KJ, Hujoel PP, Katz BP, Milgrom P, Sohn W, Stamm JW, Watson G, Wolff M, Wright T, Zero D, Aravamudhan K, Frantsve-Hawley J, Meyer DM; for the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Nonfluoride Caries-Preventive Agents. Nonfluoride caries-preventive agents. Executive summary of evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc 2011;142(9):1065-71.

- 49.Milgrom P, Söderling EM, Nelson S, Chi DL, Nakai Y. Clinical evidence for polyol efficacy. Adv Dent Res 2012; 24(2):112-6.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Ira-Lamster-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2019/08/Oral-Health-and-Alzheimers-Disease-A-Two-part-Series-4.jpg)