Polypharmacy: A Risk to Oral Health

Polypharmacy refers to the use of multiple medications, with the most accepted definition referring to a count of five or more medications.1Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr 2017;17(1):230.doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2. Other definitions include the duration of use of multiple medications and/or a different number of medications.1Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr 2017;17(1):230.doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2.,2Delara M, Murray L, Jafari B et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 2022;22:601. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03279-x. Polypharmacy is often the result of multiple morbidities, defined as the presence of at least two chronic conditions.3Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev 2013:1-9. In addition, complex treatment for a specific condition may include the use of multiple medications. In this article, we will review the prevalence and impact of polypharmacy, with a focus on dry mouth and the risk to oral health.

Polypharmacy prevalence and multiple morbidity

In a systematic review and meta-analysis reported in 2022, population-based observational studies published internationally between 1989 and 2019 on individuals older than 18 years-of-age were included.2Delara M, Murray L, Jafari B et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 2022;22:601. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03279-x. Based on the 43 studies that incorporated polypharmacy (≥5 medications), 40% of individuals experienced this. The prevalence of polypharmacy was higher in more recent studies and among individuals at least 65 years-of-age compared to younger individuals, with no differences in prevalence based on geographic region or gender. In a recent Polish study with more than 3,000 individuals aged sixty-five and older, just over 9% were not taking any medications (prescribed or over the counter).4Błeszyńska-Marunowska E, Jagiełło K, Grodzicki T et al. Prevalence, predisposing factors and strategies to reduce polypharmacy among older patients in Poland. Pol Arch Intern Med 2022 Sep 28:16347. doi: 10.20452/pamw.16347. Polypharmacy affected 53% of individuals, with 8.7% taking more than ten medications. Findings in a cross-sectional study with almost 1,900 older individuals in the community and in care homes in New Zealand were similar, with more than half of individuals taking between 5 and 9 medications and a further 10% taking at least 10 medications.5Thomson WM, Ferguson CA, Janssens BE et al. Xerostomia and polypharmacy among dependent older New Zealanders: a national survey. Age and Ageing 2021;50(1):248-51. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa099. Additionally, in a review of studies in elderly patients with diabetes, a pooled polypharmacy prevalence of 50% was observed,6Remelli F, Ceresini MG, Trevisan C et al. Prevalence and impact of polypharmacy in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022;34(9):1969-83. doi: 10.1007/s40520-022-02165-1. while in an earlier study in individuals 60 years-of-age and over, 38% ingested at least five medications daily.7Loya AM, Gonzalez-Stuart A, Rivera JO. Prevalence of polypharmacy, polyherbacy, nutritional supplement use and potential product interactions among older adults living on the United States-Mexico border: a descriptive, questionnaire-based study. Drugs Aging 2009;26:423-36. (Table 1)

Table 1. Recent findings on the prevalence of polypharmacy

| Review/Study | Findings on polypharmacy |

|---|---|

| Delara et al. (2022) Systematic review and meta-analysis. | 40% of individuals older than 18 years |

| Błeszyńska-Marunowska et al. (2022) Study (n>3,000) | 53% of individuals aged 65 and older; 8.7% taking more than 10 medications |

| Thomson et al. (2021) Cross-sectional study, ~1900 individuals. | >50% taking 5 to 9 medications; 10% taking at least 10 medications |

| Remelli et al. (2022) Study review of elderly patients with diabetes. | 50% of individuals affected |

| Loya et al. (2009) Study with subjects 60 years-of-age and over. | 38% of individuals affected |

Elderly patients experience polypharmacy more often than other age groups. However, more individuals at various stages of life are living longer with (often multiple) chronic and complex health conditions, increasing the number of individuals in both younger and older age groups affected by polypharmacy.8Desai M, Park T. Deprescribing practices in Canada: A scoping review. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2022;155(5):249-57. doi: 10.1177/17151635221114114. In one systematic review of 41 studies, the prevalence of multiple morbidities was estimated to range from 55% and up to 98% in older adults.9Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R et al. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10(4):430-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003. Amongst children, adolescents, younger and older adults, individuals with cancer and cancer survivors use multiple prescribed medications.10Betts AC, Murphy CC, Shay LA et al. Polypharmacy and medication fill nonadherence in a population-based sample of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors, 2008-2017. J Cancer Surviv 2022 Nov 8. doi: 10.1007/s11764-022-01274-0. [Epub ahead of print],11Cheng JJ, Azizoddin AM, Maranzano MJ et al. Polypharmacy in Oncology. Clin Geriatr Med 2022;38(4):705-14. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2022.05.010. Other examples of groups impacted by polypharmacy include children with chronic asthma; neurologically-impaired children and adults; younger and older adults with osteoarthritis; individuals with neuropsychiatric disorders, living with HIV or auto-immune conditions; and adults with multiple sclerosis.12Xie L, Gelfand A, Murphy CC et al. Prevalence of polypharmacy and associated adverse outcomes and risk factors among children with asthma in the USA: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022;12(10):e064708. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064708.,13Feinstein JA, Feudtner C, Kempe A, Orth LE. Anticholinergic Medications and Parent-Reported Anticholinergic Symptoms in Neurologically Impaired Children. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022:S0885-3924(22)00952-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.10.013.,14Ikram M, Shaikh NF, Sambamoorthi U. A Linear Decomposition Approach to Explain Excess Direct Healthcare Expenditures Associated with Pain Among Adults with Osteoarthritis. Health Serv Insights 2022;15:11786329221133957. doi: 10.1177/11786329221133957.,15Aguglia A, Natale A, Fusar-Poli L et al. Complex polypharmacy in bipolar disorder: Results from a real-world inpatient psychiatric unit. Psychiatry Res 2022;318:114927. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114927.,16Bevilacqua KG, Brinkley C, McGowan J et al. “We are Getting Those Old People Things.” Polypharmacy Management and Medication Adherence Among Adult HIV Patients with Multiple Comorbidities: A Qualitative Study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2022;16:2773-80. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S382005.,17Chertcoff A, Ng HS, Zhu F et al. Polypharmacy and multiple sclerosis: A population-based study. Mult Scler 2022:13524585221122207. doi: 10.1177/13524585221122207. [Epub ahead of print]

Impact of polypharmacy on health

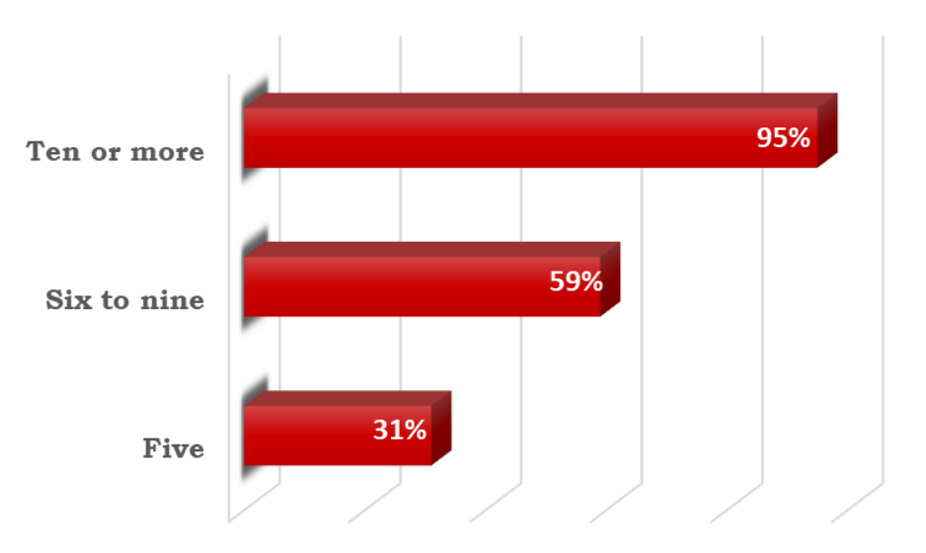

Polypharmacy-related issues include adverse drug effects, drug-drug interactions, drug-disease interactions, reduced health-related quality of life, disability and hospitalizations, decreased treatment efficacy and lower overall survival for some cancers, and reduced medication compliance.6Remelli F, Ceresini MG, Trevisan C et al. Prevalence and impact of polypharmacy in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022;34(9):1969-83. doi: 10.1007/s40520-022-02165-1.,8Desai M, Park T. Deprescribing practices in Canada: A scoping review. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2022;155(5):249-57. doi: 10.1177/17151635221114114.,11Cheng JJ, Azizoddin AM, Maranzano MJ et al. Polypharmacy in Oncology. Clin Geriatr Med 2022;38(4):705-14. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2022.05.010.,18Ye L, Yang-Huang J, Franse CB et al. Factors associated with polypharmacy and the high risk of medication-related problems among older community-dwelling adults in European countries: a longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr 2022;22(1):841. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03536-z.,19Davies LE, Spiers G, Kingston A et al. Adverse outcomes of polypharmacy in older people: systematic review of reviews. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21(2):181–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.10.022. Polypharmacy is a risk factor for poor compliance in the elderly but also in adolescents and young adults.10Betts AC, Murphy CC, Shay LA et al. Polypharmacy and medication fill nonadherence in a population-based sample of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors, 2008-2017. J Cancer Surviv 2022 Nov 8. doi: 10.1007/s11764-022-01274-0. [Epub ahead of print] An increased risk for falls and resulting hip fracture has been found for polypharmacy related to cardiovascular system and central nervous system conditions.20French DD, Campbell R, Spehar A et al. Outpatient Medications and Hip Fractures in the US. Drugs Aging 2005;22:877-85. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200522100-00006. Among older patients with diabetes, polypharmacy appears to result in poor glycemic control and an increased risk for falls.6Remelli F, Ceresini MG, Trevisan C et al. Prevalence and impact of polypharmacy in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022;34(9):1969-83. doi: 10.1007/s40520-022-02165-1. Furthermore, in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 47 studies, a significant association was found for polypharmacy and death.21Leelakanok N, Holcombe AL, Lund BC et al. Association between polypharmacy and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2017;57(6):729-38.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.06.002. (Figure 1) The estimated pooled increased mortality risk was 31%, 59% and 95%, respectively, with use of 5, 6 to 9, and 10 or more medications.

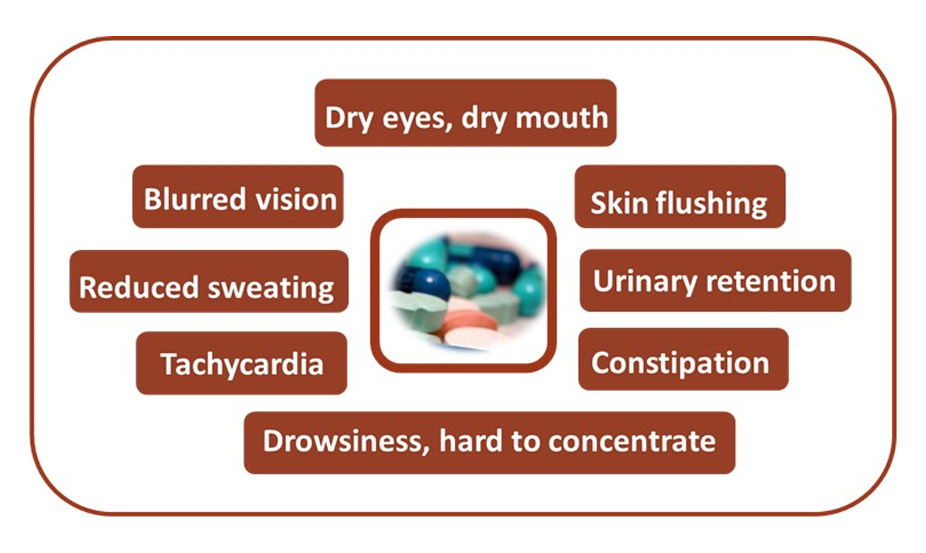

Medications with an anticholinergic effect can cause constipation, urinary retention, drowsiness, difficulty concentrating, blurred vision, skin flushing, tachycardia, reduced sweating, dry eyes and dry mouth, and may contribute to cognitive decline.13Feinstein JA, Feudtner C, Kempe A, Orth LE. Anticholinergic Medications and Parent-Reported Anticholinergic Symptoms in Neurologically Impaired Children. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022:S0885-3924(22)00952-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.10.013.,22Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D. The anticholinergic burden: from research to practice. Aust Prescr 2022;45(4):118-20. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2022.031. (Figure 2) In a recent review of prescription data for more than 220,000 individuals (1990 to 2015), up to a 900% increase in the health burden associated with anticholinergic activity of medications was found, mainly attributable to polypharmacy.23Mur J, Cox SR, Marioni RE et al. Increase in anticholinergic burden from 1990 to 2015: Age-period-cohort analysis in UK biobank. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2022;88(3):983-93. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15045. More than 30% of the total burden of drugs with an anticholinergic effect was due to antidepressants. In addition, using multiple medications with anticholinergic effects results in an ‘anticholinergic burden’, potentiating the effect of the individual medications.22Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D. The anticholinergic burden: from research to practice. Aust Prescr 2022;45(4):118-20. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2022.031. Adverse drug effects may occur decades after ceasing use of anticholinergics.23Mur J, Cox SR, Marioni RE et al. Increase in anticholinergic burden from 1990 to 2015: Age-period-cohort analysis in UK biobank. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2022;88(3):983-93. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15045.

Figure 1. Estimated pooled increase in mortality risk and medication count21Leelakanok N, Holcombe AL, Lund BC et al. Association between polypharmacy and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2017;57(6):729-38.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.06.002.

While beyond the scope of this article, other medication-induced intraoral adverse effects, depending on the medication, include soft tissue conditions such as lichenoid reactions (e.g., NSAIDs, antihypertensives, anticonvulsants, immunomodulatory drugs), aphthous ulcers and erythema multiforme (e.g., certain biologics), as well as osteonecrosis, and opportunistic infections.24Porcheri C, Mitsiadis TA. Physiology, Pathology and Regeneration of Salivary Glands. Cells 2019;8(9):976. doi: 10.3390/cells8090976.

Medications causing dry mouth and mechanisms of action

Salivary production relies on the release of acetylcholine and noradrenaline.24Porcheri C, Mitsiadis TA. Physiology, Pathology and Regeneration of Salivary Glands. Cells 2019;8(9):976. doi: 10.3390/cells8090976. These neurotransmitters are each impacted by medications. Acetylcholine binds to muscarinic acetylcholine receptors of cell membranes in the body both centrally, and peripherally through the activity of peripheral parasympathetic nerves.25Bostock C, McDonald C. Antimuscarinics in Older People: Dry Mouth and Beyond. Dent Update 2016;43(2):186-8, 191. doi: 10.12968/denu.2016.43.2.186. It is responsible for stimulating the release of large volumes of fluid in saliva, i.e., the serous component.24Porcheri C, Mitsiadis TA. Physiology, Pathology and Regeneration of Salivary Glands. Cells 2019;8(9):976. doi: 10.3390/cells8090976.,25Bostock C, McDonald C. Antimuscarinics in Older People: Dry Mouth and Beyond. Dent Update 2016;43(2):186-8, 191. doi: 10.12968/denu.2016.43.2.186. The protein-rich more viscous component of saliva is stimulated by the release of noradrenaline by the sympathetic nerves.24Porcheri C, Mitsiadis TA. Physiology, Pathology and Regeneration of Salivary Glands. Cells 2019;8(9):976. doi: 10.3390/cells8090976. Among the 100 most frequently-prescribed medications, more than 80% include xerostomia as a frequent adverse event and more than 500 medications cause dry mouth.26Yuan A, Woo SB. Adverse Drug Events in the Oral Cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2015;119(1):35-47.

Medication-induced xerostomia is largely the result of anticholinergic medications, also known as antimuscarinics.26Yuan A, Woo SB. Adverse Drug Events in the Oral Cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2015;119(1):35-47.,27Tan ECK, Lexomboon D, Sandborgh-Englund G et al. Medications That Cause Dry Mouth As an Adverse Effect in Older People: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66(1):76-84. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15151. These block the adhesion of acetylcholine to the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, preventing neurotransmission and thereby reducing salivary production.28Singh MS, Papas A. Oral Implications of Polypharmacy in the Elderly. Dent Clin N Am 2014;58:783-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2014.07.004. Medications with an anticholinergic effect include tricyclic antidepressants, antipsychotics, antiparkinson medications, antispasmodics, bronchodilators, antidiarrheals, antivertigo drugs, anti-ulcer drugs, antiemetics, muscarinic receptor antagonists for treatment of overactive bladder, alpha receptor antagonists for treatment of urinary retention, and antihistamines.26Yuan A, Woo SB. Adverse Drug Events in the Oral Cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2015;119(1):35-47.,28Singh MS, Papas A. Oral Implications of Polypharmacy in the Elderly. Dent Clin N Am 2014;58:783-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2014.07.004.,29Scully C. Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth. Oral Dis 2003;9:165–76. (Table 2) In a meta-analysis of 26 interventional and observational studies in individuals age 60 and older taking anticholinergic medications, for interventional studies a more than five-fold, four-fold and two-fold likelihood of dry mouth was found, respectively, for urological medications, antidepressants and psycholeptics.27Tan ECK, Lexomboon D, Sandborgh-Englund G et al. Medications That Cause Dry Mouth As an Adverse Effect in Older People: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66(1):76-84. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15151.

| Table 2. Medications causing dry mouth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticholinergic effect | Affecting the sympathomimetic system | |||

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Antihypertensives | |||

| Antipsychotics | Newer anti-depressants | |||

| Antiparkinson medications | Decongestants | |||

| Antispasmodics | Bronchodilators | |||

| Antihistamines | Appetite suppressants | |||

| Antiemetics | Other medications causing dry mouth | |||

| Antidiarrheals | Skeletal muscle relaxants | |||

| Anti-ulcer drugs | Hypnotics | |||

| Bronchodilators | Antimigraine drugs | |||

| Antivertigo drugs | Benzodiazepines | |||

| Muscarinic receptor antagonists for the treatment of overactive bladder |

|

|||

| Alpha receptor antagonists for the treatment of urinary retention |

|

|||

Medications affecting the sympathomimetic system include antihypertensives, newer anti-depressants (serotonin agonists, or noradrenaline and/or serotonin re-uptake blockers), decongestants (e.g., pseudoephedrine in cold medicines), bronchodilators, and appetite suppressants.29Scully C. Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth. Oral Dis 2003;9:165–76. Other medications causing dry mouth include skeletal muscle relaxants, hypnotics, antimigraine drugs, benzodiazepines, opioids, proton pump inhibitors, cytotoxic drugs, retinoids, anti-HIV drugs and cytokines. (Table 2)

Polypharmacy and dry mouth

In a retrospective study of electronic health records for individuals 65 years-of-age and older, 38.5% of participants reported xerostomia.30Storbeck T, Qian F, Marek C et al. Dose-dependent association between xerostomia and number of medications among older adults. Spec Care Dentist 2022;42:225-31. https://doi.org/10.1111/scd.12662. Polypharmacy was found to increase the likelihood of xerostomia by 38% for individuals taking between 4 and 6 medications, and doubled and more than tripled the likelihood, respectively, for individuals taking 7 to 10 or eleven or more medications.

Polypharmacy-associated dry mouth is reported to be common in adults 45 to 64 years-of-age, with 54% of individuals in a recent retrospective study taking at least five and up to fourteen medications with anticholinergic effects.31Kakkar M, Barmak AB, Arany S. Anticholinergic medication and dental caries status in middle-aged xerostomia patients-a retrospective study. J Dent Sci 2022;17(3):1206-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.12.014. Antidepressants and antipsychotics were the most frequently prescribed.

In an earlier study in individuals from 20 to 80 years-of-age, a significant increase in medication use was observed for individuals aged 60 and over compared to younger individuals.32Nederfors T, Isaksson R, Mörnstad H, Dahlöf C. Prevalence of perceived symptoms of dry mouth in an adult Swedish population – relation to age, sex and pharmacotherapy. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997;25:211-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00928.x. Seventeen percent of all individuals using no medications and 24% using one reported dry mouth, while 50% and 67% of those taking 5 and 7 medications, respectively, reported dry mouth. (Figure 3)

Normal average stimulated salivary flow = 1.5 ml/minute.

Normal average unstimulated salivary flow = 0.3 ml/minute.

In another study, stimulated and unstimulated salivary flows were compared for individuals taking no medications and those taking 1 to 3, 4 to 6, and 7 or more medications.33Närhi TO, Meurman JH, Ainamo A. Xerostomia and hyposalivation: causes, consequences and treatment in the elderly. Drugs Aging 1999;15(2):103-16. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199915020-00004. Progressive declines in salivary flow occurred as the number of medications increased. While the absolute drop in stimulated salivary flow was greater than for unstimulated salivary flow, much less unstimulated salivary flow occurs to begin with. (Figure 4) In another study, the most frequently prescribed medications for patients with schizophrenia were antipsychotics, frequently with the addition of anxiolytics.34Okamoto A, Miyachi H, Tanaka K et al. Relationship between xerostomia and psychotropic drugs in patients with schizophrenia: evaluation using an oral moisture meter. J Clin Pharm Ther 2016;41(6):684-688. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12449. While oral moisture was negatively affected by an increased number of medications, the doses taken were not significantly related with dry mouth.

Dry mouth and oral health

The functions of saliva include dental hard tissue protection through salivary clearance and dilution, buffering capacity, as a source of calcium, phosphate, mucins, proteins, and fluoride (if ingested). As such, medication-induced dry mouth results in an elevated risk for dental caries, as well as dental erosion.28Singh MS, Papas A. Oral Implications of Polypharmacy in the Elderly. Dent Clin N Am 2014;58:783-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2014.07.004.,35Buzalaf MAR, Hannas AR, Kato MT. Saliva and dental erosion. J Appl Oral Sci 2012;20(5). https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-77572012000500001. Studies showing an increase in dental caries in individuals taking anticholinergic drugs,36Jurasic MM, Gibson G, Wehler CJ et al. Caries prevalence and associations with medications and medical comorbidities. J Publ Health Dent 2019; 79:34-43. and in middle-aged adults a significantly greater risk is present as more powerful anticholinergic drugs and more of them are used.32Nederfors T, Isaksson R, Mörnstad H, Dahlöf C. Prevalence of perceived symptoms of dry mouth in an adult Swedish population – relation to age, sex and pharmacotherapy. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997;25:211-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00928.x. Since reduced salivary flow reduces the amount of calcium, phosphate, and fluoride ions available from saliva, this impacts the ability to inhibit demineralization during acid attacks and to promote remineralization when the pH rebounds. Reduced salivary flow also reduces salivary buffering capacity, enabling a more rapid and severe dip in pH as well as prolonging the time during which the pH remains below the critical level for demineralization of dental hard tissues.

In the presence of dry mouth, oral mucosa protection afforded through lubrication, salivary clearance and dilution, prevention of adhesion of microorganisms and antimicrobial agents present in saliva decreases. Bolus formation when eating, a reduced supply of zinc and gustin that are involved in taste sensation, and salivary enzymes that start the digestive process, can impact nutrition, and lubrication for eating, speaking and smiling are similarly reduced.37Nieuw Amerongen AV, Veerman ECI. Saliva – the defender of the oral cavity. Oral Dis 2002; 8:12-22. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.1o816.x Decreased salivary flow and quality also places patients at risk for oral fungal infections, fissured tongue, burning mouth and mucositis.29Scully C. Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth. Oral Dis 2003;9:165–76. Furthermore, in one study of older adults, after adjusting for confounders dry mouth was a significant factor in the risk for physical frailty.38Ohara Y, Iwasaki M, Shirobe M et al. Xerostomia as a key predictor of physical frailty among community-dwelling older adults in Japan: a five-year prospective cohort study from The Otassha Study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2022; 99:104608. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104608.

Identifying and managing patients with polypharmacy-induced dry mouth

The identification and care of patients with polypharmacy-induced dry mouth begins with a thorough medical history including a detailed medication history and oral evaluation. Since patients may not believe it is necessary to mention all medications or morbidities, it is helpful to review the information with patients and ask if there is anything else happening with their health or if there are other medications (including over the counter) that they may be taking. During the oral evaluation, hyposalivation can be assessed and any clinical presentations associated with dry mouth identified. Given the vast array of medications causing dry mouth, especially those with an anticholinergic effect, a drug formulary can be helpful in identifying these. In the case of anticholinergic polypharmacy, the Anticholinergic Risk Scale may be used to assess a patient’s cholinergic burden.25Bostock C, McDonald C. Antimuscarinics in Older People: Dry Mouth and Beyond. Dent Update 2016;43(2):186-8, 191. doi: 10.12968/denu.2016.43.2.186. This scale categorizes relevant medications by the degree to which they produce an anticholinergic effect and provides a score at the end that indicates the level of anticholinergic burden.

Patients experiencing polypharmacy and taking medications with an anticholinergic effect, as well as others causing dry mouth, should be counselled on the oral effects of their medications, and provided with oral hygiene instructions, dietary advice, and more intense preventive care. More frequent dental visits are indicated for this at-risk patient group, and it is essential to review updated medical records and to ask patients if anything has changed since their last recall. For preventive care, recommendations include in-office application of 5% sodium fluoride varnish as well as home use of a prescription-level 5000 ppm fluoride toothpaste.39Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT et al; American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Topical Fluoride Caries Preventive Agents. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0057. Prompt intervention using fluoride therapy helps to prevent incipient lesions and to arrest and reverse existing caries lesions. Fluorides are also protective against dental erosion.

Patients can be advised on the use of salivary substitutes and other therapies to relieve dry mouth and as necessary, provided with advice and treatment indicated by other oral conditions that may occur related to dry mouth.

In addition, collaboration with the patient’s medical team has been advised with the recommendation that medication review takes place with the potential to reduce or substitute medications (i.e., deprescribing), where possible, to reduce potential systemic and oral adverse effects and to improve quality of life.25Bostock C, McDonald C. Antimuscarinics in Older People: Dry Mouth and Beyond. Dent Update 2016;43(2):186-8, 191. doi: 10.12968/denu.2016.43.2.186. Deprescribing is being advocated and practiced in the medical community to help optimize medication use and to reduce inappropriate prescribing.8Desai M, Park T. Deprescribing practices in Canada: A scoping review. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2022;155(5):249-57. doi: 10.1177/17151635221114114.

Conclusions

Polypharmacy is a major health issue that has increased in prevalence over the last three decades. Elderly patients are living longer, with multiple morbidities and complex conditions that result in an increased prevalence and levels of polypharmacy. However, it is important to recognize that both older and younger patients can experience polypharmacy and be affected by the systemic and oral adverse events. Patients experiencing polypharmacy, and in the case of younger patients their parents/guardians, should be educated on the potential adverse effects. With respect to oral health, more frequent dental visits and an increased focus on oral hygiene, diet, and prevention are essential for patients experiencing polypharmacy. Collaboration with medical professionals is also recommended to help optimize care.

References

- 1.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr 2017;17(1):230.doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2.

- 2.Delara M, Murray L, Jafari B et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 2022;22:601. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03279-x.

- 3.Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev 2013:1-9.

- 4.Błeszyńska-Marunowska E, Jagiełło K, Grodzicki T et al. Prevalence, predisposing factors and strategies to reduce polypharmacy among older patients in Poland. Pol Arch Intern Med 2022 Sep 28:16347. doi: 10.20452/pamw.16347.

- 5.Thomson WM, Ferguson CA, Janssens BE et al. Xerostomia and polypharmacy among dependent older New Zealanders: a national survey. Age and Ageing 2021;50(1):248-51. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa099.

- 6.Remelli F, Ceresini MG, Trevisan C et al. Prevalence and impact of polypharmacy in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Aging Clin Exp Res 2022;34(9):1969-83. doi: 10.1007/s40520-022-02165-1.

- 7.Loya AM, Gonzalez-Stuart A, Rivera JO. Prevalence of polypharmacy, polyherbacy, nutritional supplement use and potential product interactions among older adults living on the United States-Mexico border: a descriptive, questionnaire-based study. Drugs Aging 2009;26:423-36.

- 8.Desai M, Park T. Deprescribing practices in Canada: A scoping review. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2022;155(5):249-57. doi: 10.1177/17151635221114114.

- 9.Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R et al. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10(4):430-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003.

- 10.Betts AC, Murphy CC, Shay LA et al. Polypharmacy and medication fill nonadherence in a population-based sample of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors, 2008-2017. J Cancer Surviv 2022 Nov 8. doi: 10.1007/s11764-022-01274-0. [Epub ahead of print]

- 11.Cheng JJ, Azizoddin AM, Maranzano MJ et al. Polypharmacy in Oncology. Clin Geriatr Med 2022;38(4):705-14. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2022.05.010.

- 12.Xie L, Gelfand A, Murphy CC et al. Prevalence of polypharmacy and associated adverse outcomes and risk factors among children with asthma in the USA: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022;12(10):e064708. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064708.

- 13.Feinstein JA, Feudtner C, Kempe A, Orth LE. Anticholinergic Medications and Parent-Reported Anticholinergic Symptoms in Neurologically Impaired Children. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022:S0885-3924(22)00952-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.10.013.

- 14.Ikram M, Shaikh NF, Sambamoorthi U. A Linear Decomposition Approach to Explain Excess Direct Healthcare Expenditures Associated with Pain Among Adults with Osteoarthritis. Health Serv Insights 2022;15:11786329221133957. doi: 10.1177/11786329221133957.

- 15.Aguglia A, Natale A, Fusar-Poli L et al. Complex polypharmacy in bipolar disorder: Results from a real-world inpatient psychiatric unit. Psychiatry Res 2022;318:114927. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114927.

- 16.Bevilacqua KG, Brinkley C, McGowan J et al. “We are Getting Those Old People Things.” Polypharmacy Management and Medication Adherence Among Adult HIV Patients with Multiple Comorbidities: A Qualitative Study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2022;16:2773-80. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S382005.

- 17.Chertcoff A, Ng HS, Zhu F et al. Polypharmacy and multiple sclerosis: A population-based study. Mult Scler 2022:13524585221122207. doi: 10.1177/13524585221122207. [Epub ahead of print]

- 18.Ye L, Yang-Huang J, Franse CB et al. Factors associated with polypharmacy and the high risk of medication-related problems among older community-dwelling adults in European countries: a longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr 2022;22(1):841. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03536-z.

- 19.Davies LE, Spiers G, Kingston A et al. Adverse outcomes of polypharmacy in older people: systematic review of reviews. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21(2):181–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.10.022.

- 20.French DD, Campbell R, Spehar A et al. Outpatient Medications and Hip Fractures in the US. Drugs Aging 2005;22:877-85. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200522100-00006.

- 21.Leelakanok N, Holcombe AL, Lund BC et al. Association between polypharmacy and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2017;57(6):729-38.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2017.06.002.

- 22.Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D. The anticholinergic burden: from research to practice. Aust Prescr 2022;45(4):118-20. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2022.031.

- 23.Mur J, Cox SR, Marioni RE et al. Increase in anticholinergic burden from 1990 to 2015: Age-period-cohort analysis in UK biobank. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2022;88(3):983-93. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15045.

- 24.Porcheri C, Mitsiadis TA. Physiology, Pathology and Regeneration of Salivary Glands. Cells 2019;8(9):976. doi: 10.3390/cells8090976.

- 25.Bostock C, McDonald C. Antimuscarinics in Older People: Dry Mouth and Beyond. Dent Update 2016;43(2):186-8, 191. doi: 10.12968/denu.2016.43.2.186.

- 26.Yuan A, Woo SB. Adverse Drug Events in the Oral Cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2015;119(1):35-47.

- 27.Tan ECK, Lexomboon D, Sandborgh-Englund G et al. Medications That Cause Dry Mouth As an Adverse Effect in Older People: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66(1):76-84. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15151.

- 28.Singh MS, Papas A. Oral Implications of Polypharmacy in the Elderly. Dent Clin N Am 2014;58:783-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2014.07.004.

- 29.Scully C. Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth. Oral Dis 2003;9:165–76.

- 30.Storbeck T, Qian F, Marek C et al. Dose-dependent association between xerostomia and number of medications among older adults. Spec Care Dentist 2022;42:225-31. https://doi.org/10.1111/scd.12662.

- 31.Kakkar M, Barmak AB, Arany S. Anticholinergic medication and dental caries status in middle-aged xerostomia patients-a retrospective study. J Dent Sci 2022;17(3):1206-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2021.12.014.

- 32.Nederfors T, Isaksson R, Mörnstad H, Dahlöf C. Prevalence of perceived symptoms of dry mouth in an adult Swedish population – relation to age, sex and pharmacotherapy. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997;25:211-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00928.x.

- 33.Närhi TO, Meurman JH, Ainamo A. Xerostomia and hyposalivation: causes, consequences and treatment in the elderly. Drugs Aging 1999;15(2):103-16. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199915020-00004.

- 34.Okamoto A, Miyachi H, Tanaka K et al. Relationship between xerostomia and psychotropic drugs in patients with schizophrenia: evaluation using an oral moisture meter. J Clin Pharm Ther 2016;41(6):684-688. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12449.

- 35.Buzalaf MAR, Hannas AR, Kato MT. Saliva and dental erosion. J Appl Oral Sci 2012;20(5). https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-77572012000500001.

- 36.Jurasic MM, Gibson G, Wehler CJ et al. Caries prevalence and associations with medications and medical comorbidities. J Publ Health Dent 2019; 79:34-43.

- 37.Nieuw Amerongen AV, Veerman ECI. Saliva – the defender of the oral cavity. Oral Dis 2002; 8:12-22. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.1o816.x

- 38.Ohara Y, Iwasaki M, Shirobe M et al. Xerostomia as a key predictor of physical frailty among community-dwelling older adults in Japan: a five-year prospective cohort study from The Otassha Study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2022; 99:104608. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104608.

- 39.Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT et al; American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Topical Fluoride Caries Preventive Agents. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0057.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Fiona-Collins-thumbnail-1-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2022/12/Polypharmacy-A-risk-to-oral-health-2.jpg)