Recurrent Caries

The estimated caries prevalence among adults 20 to 64 years-of-age in the United States is 90%, while for individuals 2 to 19 years-of-age it is 45.8%.1National Institute of Health. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Dental Caries (Tooth Decay) in Adults (Ages 20 to 64 Years). Available at: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/dental-caries/adults#:~:text=92%25%20of%20adults%2020%20to%2064%20have%20had,incomes%20and%20less%20education%20have%20more%20untreated%20decay.,2Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dental Caries in Primary Teeth. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/OHSR-2019-dental-caries-primary-teeth.html. With respect to untreated dental caries, an estimated prevalence of 10%, 16% and 21.3%, respectively, has been found for individuals aged 2–5 years, in the primary dentition for children aged 6–8 years, and among adults.2Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dental Caries in Primary Teeth. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/OHSR-2019-dental-caries-primary-teeth.html.,3Bashir NZ. Update on the prevalence of untreated caries in the US adult population, 2017-2020. J Am Dent Assoc 2022;153(4):300-8. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2021.09.004.

Image courtesy of Dr. Joyce Bassett

However, recurrent (secondary) caries is a further issue and can be defined as ‘a caries lesion developed adjacent to a restoration,’ and is on the same tooth.4Machiulskiene V, Campus G, Carvalho JC et al. Terminology of Dental Caries and Dental Caries Management: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by ORCA and Cariology Research Group of IADR. Caries Res 2020;54(1):7-14. doi: 10.1159/000503309. In this article, we’ll review the role of recurrent caries in restoration failure, risks factors, the caries process and its prevention and management.

Recurrent caries and restoration failures

Numerous reviews and studies have reported on recurrent caries. In a review of 12 systematic reviews (2012 through 2017), the annual failure rates (AFR) for anterior and posterior restorations ranged from 1% to 3% and 1% to 5%, respectively.5Demarco FF, Collares K, Correa MB et al. Should my composite restorations last forever? Why are they failing? Braz Oral Res 2017;31(suppl 1):e56. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0056. For posterior restorations, recurrent caries was a primary cause of failure, and poor esthetics was mainly responsible in anterior teeth. (Figure 1)

was the main cause.5Demarco FF, Collares K, Correa MB et al. Should my composite restorations last forever? Why are they failing? Braz Oral Res 2017;31(suppl 1):e56. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0056.

In a Cochrane Database review of 7 studies, recurrent caries was the most common reason for failure of posterior restorations in the permanent dentition.6Worthington HV, Khangura S, Seal K et al. Direct composite resin fillings versus amalgam fillings for permanent posterior teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;8(8):CD005620. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005620.pub3. In a separate review of prospective and retrospective studies conducted between 2011 and 2021 with a minimum 5-year follow-up, the AFR for resin-based composite restorations in the permanent dentition ranged from 0.08% to 6.3%.7Demarco FF, Cenci MS, Montagner AF et al. Longevity of composite restorations is definitely not only about materials. Dent Mater 2023;39(1):1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2022.11.009. Recurrent caries was again a main cause of failures.

In another review on RBC restorations, an overall 10-year survival rate of at least 70% was found for prospective studies.8Shisei K. Longevity of resin composite restorations. Citation Japan Dent Sci Rev 2011;47(1):43-55. http://hdl.handle.net/10069/23339. In retrospective studies, the 10-year survival rates for Class I and Class II restorations ranged from 59.9% to 89.7%. For Class III, IV and V restorations in one of the studies, the 10-year survival rates were 72.0%, 56.3% and 69.9%, respectively. Earlier reviews published in 2015 also found restoration failure in anterior teeth was primarily caused by restoration fracture or poor esthetics and recurrent caries was uncommon.9Demarco FF, Collares K, Coelho-de-Souza FH et al. Anterior composite restorations: A systematic review on long-term survival and reasons for failure. Dent Mater 2015;31(10):1214-24. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.07.005.,10Heintze SD, Rousson V, Hickel R. Clinical effectiveness of direct anterior restorations--a meta-analysis. Dent Mater 2015;31(5):481-95. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.01.015. A recent cohort study (2019) in 11 practice-based settings with 22 general dentists included almost 15,000 patients with more than 31,000 restorations placed between January 2015 and October 2017.11Laske M, Opdam NJM, Bronkhorst EM et al. Risk Factors for Dental Restoration Survival: A Practice-Based Study. J Dent Res 2019;98(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/002203451982756. Approximately 97% were resin-based composites. The AFR for Class II restorations was 7.8%, with a follow-up period of 2.7 years, and the chief cause was dental caries.

In comparing posterior composite and amalgam restorations, the overall success rate of posterior composite resin restorations based on one review was about 90% after 10 years, the same as for amalgam.10Heintze SD, Rousson V, Hickel R. Clinical effectiveness of direct anterior restorations--a meta-analysis. Dent Mater 2015;31(5):481-95. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.01.015. In contrast, for the two parallel-group studies included in a Cochrane Database review (2021), the recurrent caries rate for posterior composite restorations was approximately double that of amalgam restorations.6Worthington HV, Khangura S, Seal K et al. Direct composite resin fillings versus amalgam fillings for permanent posterior teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;8(8):CD005620. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005620.pub3. For split-mouth studies, no significant difference was found in AFR for composite and amalgam restorations. However, the authors noted that the quality of the evidence was low. In individual studies, the results are conflicting.12Al-Asmar AA, Ha Sabrah A, Abd-Raheam IM et al. Clinical evaluation of reasons for replacement of amalgam vs composite posterior restorations. Saudi Dent J 2023;35(3):275-81. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2023.02.003. ,13Santos MJMC, Rêgo HMC, Siddique I, Jessani A. Five-Year Clinical Performance of Complex Class II Resin Composite and Amalgam Restorations—A Retrospective Study. Dent J 2023;11:88. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11040088.,14Moraschini V, Fai CK, Alto RM, Dos Santos GO. Amalgam and resin composite longevity of posterior restorations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2015;43(9):1043-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.06.005.

Lastly, in a systematic review of 9 studies (1980 through 2017), the average survival rate was >90% for inlays, onlays and crowns.15Vagropoulou GI, Klifopoulou GL, Vlahou SG et al. Complications and survival rates of inlays and onlays vs complete coverage restorations: A systematic review and analysis of studies. J Oral Rehabil 2018;45(11):903-20. doi: 10.1111/joor.12695. The main biological complication was dental caries. In other research, recurrent caries again caused the largest number of failures for crowns and inlays.16Schwartz NL, Whitsett LD, Berry TG, Stewart JL. Unserviceable crowns and fixed partial dentures: Lifespan and causes for loss of serviceability. Am J Dent 1970;81:1395-401.

Risk Factors

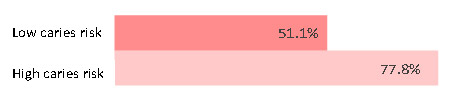

Risk factors for recurrent caries include a high caries risk level, with up to a more than four-fold risk compared to individuals at low risk for caries.5Demarco FF, Collares K, Correa MB et al. Should my composite restorations last forever? Why are they failing? Braz Oral Res 2017;31(suppl 1):e56. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0056. In one study in practice-based settings, for patients with high and low caries risk levels and no parafunctional habits, 77.8% and 51.1% of replacements were caused by dental caries.11Laske M, Opdam NJM, Bronkhorst EM et al. Risk Factors for Dental Restoration Survival: A Practice-Based Study. J Dent Res 2019;98(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/002203451982756. (Figure 2) The failure rate was higher than in controlled studies.

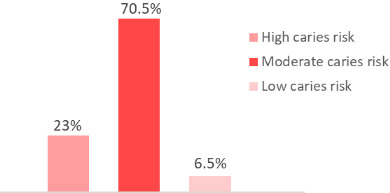

These findings are corroborated by a second practice-based setting with 76 dentists and more than 10,000 restorations placed (amalgams and composites).17Noaman BR, Fattah LD. The Relationship of Caries Risk and Oral Hygiene Level with Placement and Replacement of Dental Restorations. Clin Stomatology. Acta Medica Academica 2021;50(3):406-13. doi: 10.5644/ama2006-124.362. The majority of replacement restorations were due to recurrent caries. Among patients who had restorations replaced, 50.9% had moderate oral hygiene and 46% poor oral hygiene, while 47.7% were patients with a high caries risk level. For Class II replacement restorations, 23%, 70.5% and 6.5% of patients, respectively, had high, moderate and low caries risk levels. (Figure 3)

The risk of recurrent caries adjacent to indirect multi-unit restorations is also substantially higher for patients with poor oral hygiene, as shown in a study with a mean follow-up time of 7 years, more than 400 patients and more than 1100 multi-unit restorations.18Alenezi A, Alkhudhayri O, Altowaijri F et al. Secondary caries in fixed dental prostheses: Long-term clinical evaluation. Clin Exp Dent Res 2023;9(1):249-57. doi: 10.1002/cre2.696. The most common complication was recurrent caries (8.4% of cases). In comparing patients with poor, fair and good oral hygiene, 18.4%, 5.5% and 4% of restorations, respectively, were affected by recurrent caries. Other patient-level risk factors include increasing age, low socioeconomic status, compromised health status, periodontal disease, and the type of tooth (molar vs premolar vs anterior).7Demarco FF, Cenci MS, Montagner AF et al. Longevity of composite restorations is definitely not only about materials. Dent Mater 2023;39(1):1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2022.11.009. ,14Moraschini V, Fai CK, Alto RM, Dos Santos GO. Amalgam and resin composite longevity of posterior restorations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2015;43(9):1043-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.06.005.,18Alenezi A, Alkhudhayri O, Altowaijri F et al. Secondary caries in fixed dental prostheses: Long-term clinical evaluation. Clin Exp Dent Res 2023;9(1):249-57. doi: 10.1002/cre2.696. In addition, the clinician is considered a factor since annual failure rates vary by clinician.7Demarco FF, Cenci MS, Montagner AF et al. Longevity of composite restorations is definitely not only about materials. Dent Mater 2023;39(1):1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2022.11.009. ,14Moraschini V, Fai CK, Alto RM, Dos Santos GO. Amalgam and resin composite longevity of posterior restorations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2015;43(9):1043-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.06.005.,18Alenezi A, Alkhudhayri O, Altowaijri F et al. Secondary caries in fixed dental prostheses: Long-term clinical evaluation. Clin Exp Dent Res 2023;9(1):249-57. doi: 10.1002/cre2.696.

High surface roughness of restorative materials, associated with lack of or poor polishing or use of inferior materials, fosters bacterial adhesion and biofilm accumulation.19Özarslan M, Can DB, Avcioglu NH et al. Effect of different polishing techniques on surface properties and bacterial adhesion on resin-ceramic CAD/CAM materials. Clin Oral Investig 2022;26(8):5289-99. doi: 10.1007/s00784-022-04497-8. ,20Pinna R, Usai P, Filigheddu E et al. The role of adhesive materials and oral biofilm in the failure of adhesive resin restorations. Am J Dent 2017;30(5):285-92. Care must be taken to avoid introducing overhangs which also encourage biofilm development. Composites in particular are technique-sensitive. The presence of marginal gaps can result in bacterial adhesion and microleakage between the restoration and tooth structure. This enables the ingress of fluid and bacterial acid, promoting demineralization.13Santos MJMC, Rêgo HMC, Siddique I, Jessani A. Five-Year Clinical Performance of Complex Class II Resin Composite and Amalgam Restorations—A Retrospective Study. Dent J 2023;11:88. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11040088.

Furthermore, in a recent review the effect of the differences in elasticity of composites at their interface with enamel or dentin, where stresses develop, was evaluated.21Gauthier R, Aboulleil H, Chenal J-M et al. Consideration of Dental Tissues and Composite Mechanical Properties in Secondary Caries Development: A Critical Review. J Adhes Dent 2021;23(4):297-308. doi: 10.3290/j.jad.b1649941. Stress can result in debonding and marginal leakage, and host-derived matrix metalloproteinases can cause degradation of dentinal collagen fibers.20Pinna R, Usai P, Filigheddu E et al. The role of adhesive materials and oral biofilm in the failure of adhesive resin restorations. Am J Dent 2017;30(5):285-92. Mechanical loading can indirectly lead to a pumping action that moves cariogenic fluids into and out of microgaps, disturbing the caries balance.21Gauthier R, Aboulleil H, Chenal J-M et al. Consideration of Dental Tissues and Composite Mechanical Properties in Secondary Caries Development: A Critical Review. J Adhes Dent 2021;23(4):297-308. doi: 10.3290/j.jad.b1649941. As such, it has been proposed that the composite-tooth structure interface be investigated as a factor in the development of recurrent caries.

The caries process and recurrent caries

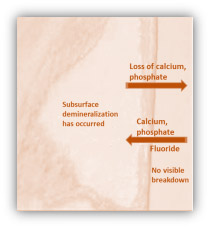

The caries process involves repeated cycles of demineralization and remineralization. Demineralization occurs due to exposure to bacterial acids produced by bacteria metabolizing fermentable carbohydrates. Cariogenic bacteria and fermentable carbohydrates are thus prerequisites for dental caries.22Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;25(3):17030. The initiation and progression of dental caries depends on the balance between risk factors and protective factors and occurs when loss of calcium and phosphate from the dental hard tissue (demineralization) outpaces remineralization.6Worthington HV, Khangura S, Seal K et al. Direct composite resin fillings versus amalgam fillings for permanent posterior teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;8(8):CD005620. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005620.pub3.,7Demarco FF, Cenci MS, Montagner AF et al. Longevity of composite restorations is definitely not only about materials. Dent Mater 2023;39(1):1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2022.11.009. Remineralization occurs if conditions are favorable, and in the presence of fluoride is accelerated. Fluoride adsorbs to the partially demineralized surface and attracts calcium ions, which attract phosphate. (Figure 4)

This process also occurs with recurrent caries lesions, with the difference being that the lesion is adjacent to a restoration. In an in situ study, samples of sound dentin and enamel and samples restored with resin-based composite were embedded in full dentures worn by 8 subjects for almost five months.23Thomas RZ, van der Mei HC, van der Veen MH et al. Bacterial composition and red fluorescence of plaque in relation to primary and secondary caries next to composite: an in situ study. J Oral Microbiol Immunol 2008;23(1):7-13. A significantly greater combined proportion of lactobacilli and streptococcus mutans were observed on the restored samples compared to the unrestored samples. Based on this, it appears that for lesions adjacent to composite restorations the process may differ to an extent from primary caries with respect to the mix of cariogenic flora, due to the local environment.

Preventing and managing recurrent caries

Caries prevention and control measures for individual patients with recurrent caries or primary caries are similar and include oral hygiene instructions and thorough home care, as well as dietary and lifestyle advice. Other preventive measures can include applications of in-office topical fluorides and home use of OTC/Rx gels toothpastes, and rinses.25Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT et al; American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Topical Fluoride Caries Preventive Agents. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0057. Erratum in: J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(12):1335. Dosage error in article text. Patients should also receive periodic caries risk assessments since caries activity changes over time, to help determine appropriate preventive care for the individual.26American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age 0-6). Available at: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/FIles/topics_caries_under6.pdf.,27American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age >6). Available at: http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/Files/topic_caries_over6.ashx.,28AAPD. Caries-risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Latest revision, 2019. Available at: https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf The best predictor for future caries is the presence of active caries lesions, and it is necessary to consider lesion activity and the site in determining appropriate treatment. In addition, polishing of direct and indirect restorations at the time of placement is important to minimize the surface roughness of the restorative material, as is the avoidance of even small overhangs during restorative care, since both help to reduce the likelihood of bacterial adhesion and dental biofilm on the restoration and at the restoration-tooth interface.

In the case of incipient recurrent caries, caries arrestment or reversal may be possible and the guidelines for the non-restorative management of caries lesions published by the American Dental Association can be consulted for potential options.29Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(10):837-49. e19. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002. (Table 1) For cavitated coronal lesions in primary and permanent teeth, 6-monthly application of 38% silver diamine fluoride (SDF) is prioritized over 5% NaF varnish applied weekly for 3 weeks. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry supports the use of SDF for caries arrestment.30American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the use of silver diamine fluoride for pediatric dental patients. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2022:72-5. Available at: https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_SilverDiamine.pdf. For root caries lesions, the use of 5,000 ppm fluoride toothpaste/gel at least once daily is the highest priority recommendation for caries arrestment and reversal.

| Table 1. Preventing and managing recurrent caries | |

|---|---|

| Prevention |

|

| Management |

|

| Patients should receive periodic caries risk assessments to help determine appropriate care for the individual. | |

If it is determined that restorative care is required for a recurrent caries lesion, it is recommended that a minimally invasive approach be used. If possible, locally repairing the restoration rather than replacing it helps to preserve dental hard tissue and avoid the cycle of loss of hard tissue with repeated interventions.7Demarco FF, Cenci MS, Montagner AF et al. Longevity of composite restorations is definitely not only about materials. Dent Mater 2023;39(1):1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2022.11.009. ,24Mjor IA. Clinical diagnosis of recurrent caries. J Am Dent Assoc 2005;136(10):1426-33. ,31Featherstone JDB. Dental restorative materials containing quaternary ammonium compounds have sustained antibacterial action. J Am Dent Assoc 2022:153(12):1114-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2022.09.006.

Discussion

The impact of recurrent caries in studies is greater over time, with shorter follow-up periods favoring reasons other than recurrent caries.32Kerschbaum T, Voß R. Die praktische Bewährung von Krone und Inlay. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z 1981;36:243-9.,33Ástvaldsdóttir Á, Dagerhamn J, van Dijken JW et al. Longevity of posterior resin composite restorations in adults – A systematic review. J Dent 2015;43(8):934-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.05.001. Several studies have reported recurrent caries becoming the main cause of failure four or five years after restoration placement onwards, with fracture the main cause of failure until then.5Demarco FF, Collares K, Correa MB et al. Should my composite restorations last forever? Why are they failing? Braz Oral Res 2017;31(suppl 1):e56. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0056.,8Shisei K. Longevity of resin composite restorations. Citation Japan Dent Sci Rev 2011;47(1):43-55. http://hdl.handle.net/10069/23339.,13Santos MJMC, Rêgo HMC, Siddique I, Jessani A. Five-Year Clinical Performance of Complex Class II Resin Composite and Amalgam Restorations—A Retrospective Study. Dent J 2023;11:88. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11040088. Additionally, while secondary caries was relatively rare based on a review of prospective studies it was noted that recurrent caries is a principal cause of restoration failure in the real-world general practice. Furthermore, many studies included in reviews are from prior decades while significant material advances in restorative materials and adhesive technologies have since occurred.

Recurrent caries can also be difficult to detect and assess. Lesions must be differentiated from marginal discoloration, composite wear, and minor marginal defects, and inactive lesions differentiated from active lesions.5Demarco FF, Collares K, Correa MB et al. Should my composite restorations last forever? Why are they failing? Braz Oral Res 2017;31(suppl 1):e56. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0056.,8Shisei K. Longevity of resin composite restorations. Citation Japan Dent Sci Rev 2011;47(1):43-55. http://hdl.handle.net/10069/23339.,24Mjor IA. Clinical diagnosis of recurrent caries. J Am Dent Assoc 2005;136(10):1426-33. In addition, arrested residual caries may gradually appear darker and be mistaken for active caries lesions.5Demarco FF, Collares K, Correa MB et al. Should my composite restorations last forever? Why are they failing? Braz Oral Res 2017;31(suppl 1):e56. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0056. Recent and current developments in caries detection technology should improve the ability to accurately detect secondary caries lesions and determine lesion activity. Furthermore, the decision-making criteria used for the replacement of posterior restorations influence the treatment provided. This results in different decisions for the primary dentition, based on the system being used.34Moro BLP, Freitas RD, Pontes LRA et al. Influence of different clinical criteria on the decision to replace restorations in primary teeth. J Dent 2020;101:103421. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103421.

Recent developments

Recent research has focused on the development of novel restorative materials that would inhibit recurrent caries. These include the inclusion of bioactive materials, surface coatings that inhibit biofilm formation, remineralizing materials, and antibacterials.35Zhou W, Chen H, Weir MD et al. Novel bioactive dental restorations to inhibit secondary caries in enamel and dentin under oral biofilms. J Dent 2023;133:104497. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2023.104497. ,36Sterzenbach T, Helbig R, Hannig C, Hannig M. Bioadhesion in the oral cavity and approaches for biofilm management by surface modifications. Clin Oral Investig 2020;24(12):4237-60. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03646-1. Bioactive luting cements based on a combination of calcium aluminate and glass ionomer are an example. These form a self-repairing hydroxyapatite layer and helps to preserve long-term marginal integrity, and in a three-year study no discoloration or recurrent caries was found.37Jefferies SR, Pameijer CH, Appleby DC et al. A bioactive dental luting cement--its retentive properties and 3-year clinical findings. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2013;34(Spec No 1):2-9. Experimentally, the use of hydrophilic bioactive resin-based surface coatings containing calcium silicate or proanthocyanidins has resulted in significant decreases in permeability and demineralization and increases in enamel and dentin hardness.38Firoozmand LM, Alania Y, Bedran-Russo AK. Development and Assessment of Bioactive Coatings for the Prevention of Recurrent Caries Around Resin Composite Restorations. Oper Dent 2022;47(3):E152-E161. doi: 10.2341/20-299-L. At the current time, composite restorative materials are available that contain quaternary ammonium as an antibacterial agent.32Kerschbaum T, Voß R. Die praktische Bewährung von Krone und Inlay. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z 1981;36:243-9. Nanoparticles of zinc, silver, and titanium; quaternary ammonium compounds; and other agents are being researched for their ability to disrupt bacterial metabolism and inhibit biofilm formation.39Nizami MZI, Xu VW, Yin IX et al. Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles in Caries Prevention: A Review. Nanomaterials 2021;11(12):3446. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11123446.,40Wu R, Zhao Q, Lu S et al. Inhibitory effect of reduced graphene oxide-silver nanocomposite on progression of artificial enamel caries. J Appl Oral Sci 2018;27:e20180042. Other candidates include an adhesive containing dimethylaminohexadecyl methacrylate and nanoparticles of amorphous calcium phosphate, which is being investigated for its ability to inhibit matrix metalloproteinases, and to promote remineralization.41Wu L, Cao X, Meng Y et al. Novel bioactive adhesive containing dimethylaminohexadecyl methacrylate and calcium phosphate nanoparticles to inhibit metalloproteinases and nanoleakage with three months of aging in artificial saliva. Dent Mater 2022;38(7):1206-17. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2022.06.017.

Conclusions

Recurrent caries is a major cause of restoration failure over time in the posterior dentition. It is also acknowledged that recurrent caries plays an increasing role as the cause of restoration failure over time. Traditional caries risk factors including patient variables determine risk level for recurrent caries, together with restorative material selection and clinical technique. Future research has been proposed to include patient variables and risk factors in the design of randomized clinical trials. Research has also been recommended to improve the detection and assessment of recurrent caries, and to determine the most appropriate non-invasive and minimally invasive interventions.5Demarco FF, Collares K, Correa MB et al. Should my composite restorations last forever? Why are they failing? Braz Oral Res 2017;31(suppl 1):e56. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0056.,8Shisei K. Longevity of resin composite restorations. Citation Japan Dent Sci Rev 2011;47(1):43-55. http://hdl.handle.net/10069/23339.,11Laske M, Opdam NJM, Bronkhorst EM et al. Risk Factors for Dental Restoration Survival: A Practice-Based Study. J Dent Res 2019;98(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/002203451982756.

In the meantime, careful technique and the selection of appropriate, quality restorative materials are indicated when placing restorations to reduce the risk of recurrent caries associated with material and clinical factors. As with primary caries, preventive measures are needed based on the patient’s risk level – which requires periodic caries risk assessment. When other interventions are required, non-invasive measures are preferable and should retreatment be necessary, repair rather than replacement should be considered to avoid a cycle of expanded restorative care and help preserve tooth structure.

References

- 1.National Institute of Health. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Dental Caries (Tooth Decay) in Adults (Ages 20 to 64 Years). Available at: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/dental-caries/adults#:~:text=92%25%20of%20adults%2020%20to%2064%20have%20had,incomes%20and%20less%20education%20have%20more%20untreated%20decay.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dental Caries in Primary Teeth. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/OHSR-2019-dental-caries-primary-teeth.html.

- 3.Bashir NZ. Update on the prevalence of untreated caries in the US adult population, 2017-2020. J Am Dent Assoc 2022;153(4):300-8. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2021.09.004.

- 4.Machiulskiene V, Campus G, Carvalho JC et al. Terminology of Dental Caries and Dental Caries Management: Consensus Report of a Workshop Organized by ORCA and Cariology Research Group of IADR. Caries Res 2020;54(1):7-14. doi: 10.1159/000503309.

- 5.Demarco FF, Collares K, Correa MB et al. Should my composite restorations last forever? Why are they failing? Braz Oral Res 2017;31(suppl 1):e56. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0056.

- 6.Worthington HV, Khangura S, Seal K et al. Direct composite resin fillings versus amalgam fillings for permanent posterior teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;8(8):CD005620. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005620.pub3.

- 7.Demarco FF, Cenci MS, Montagner AF et al. Longevity of composite restorations is definitely not only about materials. Dent Mater 2023;39(1):1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2022.11.009.

- 8.Shisei K. Longevity of resin composite restorations. Citation Japan Dent Sci Rev 2011;47(1):43-55. http://hdl.handle.net/10069/23339.

- 9.Demarco FF, Collares K, Coelho-de-Souza FH et al. Anterior composite restorations: A systematic review on long-term survival and reasons for failure. Dent Mater 2015;31(10):1214-24. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.07.005.

- 10.Heintze SD, Rousson V, Hickel R. Clinical effectiveness of direct anterior restorations--a meta-analysis. Dent Mater 2015;31(5):481-95. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.01.015.

- 11.Laske M, Opdam NJM, Bronkhorst EM et al. Risk Factors for Dental Restoration Survival: A Practice-Based Study. J Dent Res 2019;98(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/002203451982756.

- 12.Al-Asmar AA, Ha Sabrah A, Abd-Raheam IM et al. Clinical evaluation of reasons for replacement of amalgam vs composite posterior restorations. Saudi Dent J 2023;35(3):275-81. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2023.02.003.

- 13.Santos MJMC, Rêgo HMC, Siddique I, Jessani A. Five-Year Clinical Performance of Complex Class II Resin Composite and Amalgam Restorations—A Retrospective Study. Dent J 2023;11:88. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11040088.

- 14.Moraschini V, Fai CK, Alto RM, Dos Santos GO. Amalgam and resin composite longevity of posterior restorations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2015;43(9):1043-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.06.005.

- 15.Vagropoulou GI, Klifopoulou GL, Vlahou SG et al. Complications and survival rates of inlays and onlays vs complete coverage restorations: A systematic review and analysis of studies. J Oral Rehabil 2018;45(11):903-20. doi: 10.1111/joor.12695.

- 16.Schwartz NL, Whitsett LD, Berry TG, Stewart JL. Unserviceable crowns and fixed partial dentures: Lifespan and causes for loss of serviceability. Am J Dent 1970;81:1395-401.

- 17.Noaman BR, Fattah LD. The Relationship of Caries Risk and Oral Hygiene Level with Placement and Replacement of Dental Restorations. Clin Stomatology. Acta Medica Academica 2021;50(3):406-13. doi: 10.5644/ama2006-124.362.

- 18.Alenezi A, Alkhudhayri O, Altowaijri F et al. Secondary caries in fixed dental prostheses: Long-term clinical evaluation. Clin Exp Dent Res 2023;9(1):249-57. doi: 10.1002/cre2.696.

- 19.Özarslan M, Can DB, Avcioglu NH et al. Effect of different polishing techniques on surface properties and bacterial adhesion on resin-ceramic CAD/CAM materials. Clin Oral Investig 2022;26(8):5289-99. doi: 10.1007/s00784-022-04497-8.

- 20.Pinna R, Usai P, Filigheddu E et al. The role of adhesive materials and oral biofilm in the failure of adhesive resin restorations. Am J Dent 2017;30(5):285-92.

- 21.Gauthier R, Aboulleil H, Chenal J-M et al. Consideration of Dental Tissues and Composite Mechanical Properties in Secondary Caries Development: A Critical Review. J Adhes Dent 2021;23(4):297-308. doi: 10.3290/j.jad.b1649941.

- 22.Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;25(3):17030.

- 23.Thomas RZ, van der Mei HC, van der Veen MH et al. Bacterial composition and red fluorescence of plaque in relation to primary and secondary caries next to composite: an in situ study. J Oral Microbiol Immunol 2008;23(1):7-13.

- 24.Mjor IA. Clinical diagnosis of recurrent caries. J Am Dent Assoc 2005;136(10):1426-33.

- 25.Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT et al; American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Topical Fluoride Caries Preventive Agents. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0057. Erratum in: J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(12):1335. Dosage error in article text.

- 26.American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age 0-6). Available at: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/FIles/topics_caries_under6.pdf.

- 27.American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age >6). Available at: http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/Files/topic_caries_over6.ashx.

- 28.AAPD. Caries-risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Latest revision, 2019. Available at: https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf

- 29.Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(10):837-49. e19. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002.

- 30.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the use of silver diamine fluoride for pediatric dental patients. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2022:72-5. Available at: https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_SilverDiamine.pdf.

- 31.Featherstone JDB. Dental restorative materials containing quaternary ammonium compounds have sustained antibacterial action. J Am Dent Assoc 2022:153(12):1114-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2022.09.006.

- 32.Kerschbaum T, Voß R. Die praktische Bewährung von Krone und Inlay. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z 1981;36:243-9.

- 33.Ástvaldsdóttir Á, Dagerhamn J, van Dijken JW et al. Longevity of posterior resin composite restorations in adults – A systematic review. J Dent 2015;43(8):934-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.05.001.

- 34.Moro BLP, Freitas RD, Pontes LRA et al. Influence of different clinical criteria on the decision to replace restorations in primary teeth. J Dent 2020;101:103421. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103421.

- 35.Zhou W, Chen H, Weir MD et al. Novel bioactive dental restorations to inhibit secondary caries in enamel and dentin under oral biofilms. J Dent 2023;133:104497. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2023.104497.

- 36.Sterzenbach T, Helbig R, Hannig C, Hannig M. Bioadhesion in the oral cavity and approaches for biofilm management by surface modifications. Clin Oral Investig 2020;24(12):4237-60. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03646-1.

- 37.Jefferies SR, Pameijer CH, Appleby DC et al. A bioactive dental luting cement--its retentive properties and 3-year clinical findings. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2013;34(Spec No 1):2-9.

- 38.Firoozmand LM, Alania Y, Bedran-Russo AK. Development and Assessment of Bioactive Coatings for the Prevention of Recurrent Caries Around Resin Composite Restorations. Oper Dent 2022;47(3):E152-E161. doi: 10.2341/20-299-L.

- 39.Nizami MZI, Xu VW, Yin IX et al. Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles in Caries Prevention: A Review. Nanomaterials 2021;11(12):3446. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11123446.

- 40.Wu R, Zhao Q, Lu S et al. Inhibitory effect of reduced graphene oxide-silver nanocomposite on progression of artificial enamel caries. J Appl Oral Sci 2018;27:e20180042.

- 41.Wu L, Cao X, Meng Y et al. Novel bioactive adhesive containing dimethylaminohexadecyl methacrylate and calcium phosphate nanoparticles to inhibit metalloproteinases and nanoleakage with three months of aging in artificial saliva. Dent Mater 2022;38(7):1206-17. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2022.06.017.