The Dangers of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages: Dental Professionals Must Respond

The threat to health posed by over-consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) is well documented. These beverages include sodas, energy and vitamin drinks, fruit juice and other soft drinks containing added sugars.1Bleich SN, Vercammen KA. The negative impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on children’s health: an update of the literature. BMC Obesity 2018;5:6,2Hu FB. Resolved: There is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev 2013;14(8):606-19.,3Luger M, Lafontan M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Winzer E, Yumuk V, Farpour-Lambert N. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review from 2013 to 2015 and a comparison with previous studies. Obes Facts 2017;10:674-93. SSB promote weight gain and the adverse health effects associated with being overweight or obese.2Hu FB. Resolved: There is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev 2013;14(8):606-19.,3Luger M, Lafontan M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Winzer E, Yumuk V, Farpour-Lambert N. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review from 2013 to 2015 and a comparison with previous studies. Obes Facts 2017;10:674-93.

This has led to a call for renewed efforts to reduce SSB consumption, including taxation, labeling changes and behavioral interventions.4Lee BY, Ferguson MC, Hertenstein DL, Adam A, Zenkov E, Wang PI, Wong MS, Gittelsohn J, Mui Y, Brown ST. Simulating the impact of sugar-sweetened beverage warning labels in three cities. Am J Prev Med 2018;54(2):197-204. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.11.003.,5Abdel Rahman A, Jomaa L, Kahale LA, Adair P, Pine C. Effectiveness of behavioral interventions to reduce the intake of sugar-sweetened beverages in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 2018;76(2):88-107. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nux061. The role of dental professionals in this effort must also be considered. This is in relationship to the larger issue of dental professionals applying a common risk factor approach to emphasize the importance of prevention as fundamental to controlling the development and progression of many oral and systemic diseases.

Health Impact of SSB

In a systematic review of 30 studies conducted between January 2013 and October 2015, a significant association was found for SSB consumption and weight gain in children and adults.3Luger M, Lafontan M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Winzer E, Yumuk V, Farpour-Lambert N. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review from 2013 to 2015 and a comparison with previous studies. Obes Facts 2017;10:674-93. Further, in an Australian study of children 2 to 16 years-of-age, consuming at least 2 servings of SSB daily (>250 g/day) carried a 26% greater risk of being overweight or obese compared to consuming less.6Grimes CA, Riddell LJ, Campbell KJ, Nowson CA. Dietary salt intake, sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, and obesity risk. Pediatrics 2013;131(1):14-21. A majority of studies in another review also support a relationship between SSB consumption and insulin resistance in children and adolescents.1Bleich SN, Vercammen KA. The negative impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on children’s health: an update of the literature. BMC Obesity 2018;5:6. Since childhood obesity is associated with asthma, attention-deficit disorder, and reduced quality of life and educational achievement,7Bussiek P-BV, De Poli C, Bevan G. A scoping review protocol to map the evidence on interventions to prevent overweight and obesity in children. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019311. reduction in SSB consumption is an important public health initiative. Studies further highlight a relationship between adult consumption of SSB, and diabetes mellitus (DM) and cardiovascular disease, with a direct dose-response observed for long-term weight gain and DM.2Hu FB. Resolved: There is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev 2013;14(8):606-19. Globally, an estimated 184,000 deaths per year are associated with intake of SSB, with 72.3%, 24.2% and 3.5% of these deaths attributed to DM, cardiovascular disease and cancers, respectively.8Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Lim S, Ezzati M, Mozaffarian D; Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group (NutriCoDE). Estimated global, regional, and national disease burdens related to sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in 2010. Circulation 2015;132:639-66. (Figure 1)

Consumption of SSB is clearly associated with dental caries. Third graders in one study from the United States were found to consume an average of 2 SSB per day.9Wilder JR, Kaste LM, Handler A, Chapple-McGruder T, Rankin KM. The association between sugar-sweetened beverages and dental caries among third-grade students in Georgia. J Public Health Dent 2016;76:76-84. After adjusting for socioeconomic status and maternal oral health, a 22% increase in dental caries was found for each additional SSB consumed daily. Greater SSB consumption has also been found to result in up to a four-fold increased risk of severe early childhood caries.10Evans EW, Hayes C, Palmer CA, Bermudez OI, Cohen SA, Must A. Dietary intake and severe early childhood caries in low-income, young children. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113(8):1057-61. In adolescents, intake of SSB has been found to be associated with toothache and food avoidance due to dental discomfort, with consumption of energy and sports drinks noted to be of particular concern.11Hardy LL, Bell J, Bauman A, Mihrshahi S. Association between adolescents’ consumption of total and different types of sugar-sweetened beverages with oral health impacts and weight status. Aust N Z J Public Health 2018;42(1):22-6. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12749.

Effect of Reduced Intake of SSB

Recent randomized controlled clinical trials have confirmed health improvements following reduced intake of SSB.1Bleich SN, Vercammen KA. The negative impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on children’s health: an update of the literature. BMC Obesity 2018;5:6.,2Hu FB. Resolved: There is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev 2013;14(8):606-19.,12de Ruyter JC, Olthof MR, Seidell JC, Katan MB. A trial of sugar-free or sugar-sweetened beverages and body weight in children. N Engl J Med 2012;367(15):1397-406. In a Dutch study, more than 600 children 4 to 11 years-of-age, and of normal weight, received 8 oz. (250 ml) of a sugar-free drink or an SSB daily for 18 months. Reduced weight gain was observed in the group receiving sugar-free drinks.12de Ruyter JC, Olthof MR, Seidell JC, Katan MB. A trial of sugar-free or sugar-sweetened beverages and body weight in children. N Engl J Med 2012;367(15):1397-406. In another study, among English children ages 7 to 11 years, fewer children in the group receiving 4 educational sessions that discouraged SSB consumption were overweight at the end of the school year than in the control group, although this benefit was not sustained.13James J, Thomas P, Kerr D. Preventing childhood obesity: two year followup results from the Christchurch obesity prevention programme in schools (CHOPPS). BMJ 2007;335(7623):762. In a third study with more than 200 adolescents, weight reductions were again observed in the intervention group at the end of 12 months, but not sustained.14Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Chomitz VR, Antonelli TA, Gortmaker SL, Osganian SK, Ludwig DS. A randomized trial of sugar-sweetened beverages and adolescent body weight. N Engl J Med 2012;367(15):1407-16.

Policy Interventions to Reduce SSB Consumption

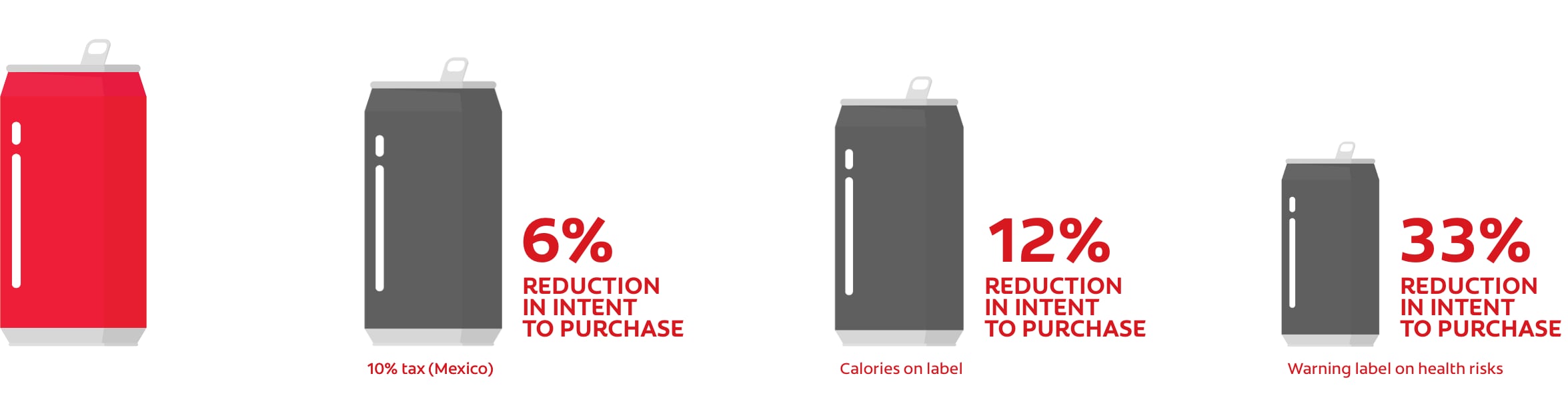

Placement of health warning labels on SSB regarding their association with obesity, DM and tooth decay may reduce intent-to-purchase. In an online survey of more than 2000 parents, 40% of parents would select an SSB with a warning label.

Figure 2.

Influence of taxes and labeling on consumption and selection of SSB

Role of Dental Professionals

A recent review of interventions for Native American children and adolescents in Alaska concluded that a variety of approaches should be emphasized, including education of the entire family and a community-based approach.28Chi DL. Reducing Alaska Native paediatric oral health disparities: a systematic review of oral health interventions and a case study on multilevel strategies to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage intake. Int J Circumpolar Health 2013;72:21066. This analysis emphasized the need for culturally-appropriate interventions. Another review examined interventions that could help children younger than 12 years-of-age.

Two studies involving dental offices were identified, in which dental

In an online survey of pediatric dentists and dental residents, 94% of more than 1600 respondents indicated that they provided information and advice on SSB.26Wright R, Casamassimo PS. Assessing attitudes and actions of pediatric dentists toward childhood obesity and sugar-sweetened beverages. J Pub Health Dent 2017;77:S79-S87. While only 17% offered additional interventions for childhood obesity, a majority of the remaining respondents stated that they would be interested in doing so. Weight and height measurements, and advice were most frequently provided. Other surveys also indicate that few dental professionals provide obesity interventions or are comfortable discussing weight.29Curran AE, Caplan DJ, Lee JY, Paynter L, Gizlice Z, Champagne C, Agans R. Dentists’ attitudes about their role in addressing obesity in patients: a national survey. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141(11):1307-16.,30Braithwaite AS, Vann J, William F, Switzer BR, Boyd KL, Lee JY. Nutritional counseling practices: how do North Carolina pediatric dentists weigh in? Pediatr Dent 2008;30(6):488-95. (Table 1)

| Table 1. Roles for dental professionals |

|---|

| Nutritional and obesity education for patients |

| Patient education on a healthy lifestyle and physical activity |

| Community-based education |

| Medical referrals for overweight and at-risk individuals |

| Motivational interviewing and active listening |

| Weight and height measurements |

Barriers to Interventions by Dental Professionals

Barriers to providing education and other interventions for childhood obesity in the dental office include a perceived lack of parental interest and acceptance, parental dissatisfaction, fear of offending parents and giving the appearance of being judgmental.26Wright R, Casamassimo PS. Assessing attitudes and actions of pediatric dentists toward childhood obesity and sugar-sweetened beverages. J Pub Health Dent 2017;77:S79-S87.,29Curran AE, Caplan DJ, Lee JY, Paynter L, Gizlice Z, Champagne C, Agans R. Dentists’ attitudes about their role in addressing obesity in patients: a national survey. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141(11):1307-16.,31Lee JY, Caplan DJ, Gizlice Z, Ammerman A, Agans R, Curran AE. US pediatric dentists’ counseling practices in addressing childhood obesity. Pediatr Dent 2012;34(3):245-50.,32Bell KP, Phillips C, Paquette DW, Offenbacher S, Wilder RS. Incorporating oral-systemic evidence into patient care: practice behaviors and barriers of North Carolina dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg 2011;85(2):99-113. Lack of time, the lack of trained personnel, limited personal knowledge or training on nutrition and obesity, absence of appropriate referral options, and lack of or inadequate reimbursement are also barriers.26Wright R, Casamassimo PS. Assessing attitudes and actions of pediatric dentists toward childhood obesity and sugar-sweetened beverages. J Pub Health Dent 2017;77:S79-S87.,29Curran AE, Caplan DJ, Lee JY, Paynter L, Gizlice Z, Champagne C, Agans R. Dentists’ attitudes about their role in addressing obesity in patients: a national survey. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141(11):1307-16.,31Lee JY, Caplan DJ, Gizlice Z, Ammerman A, Agans R, Curran AE. US pediatric dentists’ counseling practices in addressing childhood obesity. Pediatr Dent 2012;34(3):245-50.,32Bell KP, Phillips C, Paquette DW, Offenbacher S, Wilder RS. Incorporating oral-systemic evidence into patient care: practice behaviors and barriers of North Carolina dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg 2011;85(2):99-113. Eighty-one percent of respondents believed that parents accept advice on SSB consumption while only 14% and 7%, respectively, held the same belief with respect to obesity education and screening.26Wright R, Casamassimo PS. Assessing attitudes and actions of pediatric dentists toward childhood obesity and sugar-sweetened beverages. J Pub Health Dent 2017;77:S79-S87. In contrast, in another study the dental setting was considered appropriate for height and weight measurements, and information on a healthy diet and physical activity, by 88% and 95% of parents, respectively.33Tavares M, Chomitz V. A healthy weight intervention for children in a dental setting: a pilot study. J Am Dent Assoc 2009;140(3):313-6. In a 2017 systematic review only three studies were found that reported nutritional or obesity-related training in dental and dental hygiene schools.34Divaris K, Bhaskar V, McGraw KA. Pediatric obesity-related curricular content and training in dental schools and dental hygiene programs: systematic review and recommendations. J Public Health Dent 2017;77(Suppl 1):S96-S103. The World Health Organization, however, recommends that nutritional training be incorporated globally into the dental curriculum.35Moynihan P. Sugars and dental caries: Evidence for setting a recommended threshold for intake 1–3. Adv Nutr 2016;7:149-56.

Conclusions

Reducing intake of SSB requires the efforts of the entire community, including active participation and collaboration by all members of the health care team.9Wilder JR, Kaste LM, Handler A, Chapple-McGruder T, Rankin KM. The association between sugar-sweetened beverages and dental caries among third-grade students in Georgia. J Public Health Dent 2016;76:76-84. Dental professionals can to play an important role in this effort by educating patients on the risks associated with SSB, and by influencing policy.36Sanghavi A, Siddiqui NJ. Advancing oral health policy and advocacy to prevent childhood obesity and reduce children’s consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. J Public Health Dent 2017;77(Suppl 1):S88-S95. Standardized training and continuing education programs are required to provide dental professionals with the knowledge to fulfil this role.35Moynihan P. Sugars and dental caries: Evidence for setting a recommended threshold for intake 1–3. Adv Nutr 2016;7:149-56. Further research is required on interprofessional collaboration to address childhood obesity and oral disease, and on evidence-based interventions that will be most effective.7Bussiek P-BV, De Poli C, Bevan G. A scoping review protocol to map the evidence on interventions to prevent overweight and obesity in children. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019311.,24Dooley D, Moultrie NM, Sites E, Crawford PB. Primary care interventions to reduce childhood obesity and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption: Food for thought for oral health professionals. J Public Health Dent 2017;77(Suppl 1):S104-S127.,25Mallonee LF, Boyd LD, Stegeman C. A scoping review of skills and tools oral health professionals need to engage children and parents in dietary changes to prevent childhood obesity and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. J Public Health Dent 2017;77(Suppl 1):S128-S135. In the meantime, there is increasing awareness among dental professionals of their role in educating patients and parents on both dental caries and childhood obesity.36Sanghavi A, Siddiqui NJ. Advancing oral health policy and advocacy to prevent childhood obesity and reduce children’s consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. J Public Health Dent 2017;77(Suppl 1):S88-S95.

References

- 1.Dominy SS, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv. 2019;5(1):eaau3333 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30746447.

- 2.Sadrameli M, et al. Linking mechanisms of periodontitis to Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020;33(2):230-8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32097126.

- 3.Borsa L, et al. Analysis the link between periodontal diseases and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34501899.

- 4.Costa MJF, et al. Relationship of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of pre-clinical studies. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(3):797-806 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33469718.

- 5.Munoz Fernandez SS, Lima Ribeiro SM. Nutrition and Alzheimer disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(4):677-97 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30336995.

- 6.Aquilani R, et al. Is the Brain Undernourished in Alzheimer’s Disease? Nutrients. 2022;14(9) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35565839.

- 7.Fukushima-Nakayama Y, et al. Reduced mastication impairs memory function. J Dent Res. 2017;96(9):1058-66 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28621563.

- 8.Kim HB, et al. Abeta accumulation in vmo contributes to masticatory dysfunction in 5XFAD Mice. J Dent Res. 2021;100(9):960-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33719684.

- 9.Miura H, et al. Relationship between cognitive function and mastication in elderly females. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30(8):808-11 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12880404.

- 10.Lexomboon D, et al. Chewing ability and tooth loss: association with cognitive impairment in an elderly population study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1951-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23035667.

- 11.Elsig F, et al. Tooth loss, chewing efficiency and cognitive impairment in geriatric patients. Gerodontology. 2015;32(2):149-56 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24128078.

- 12.Kim EK, et al. Relationship between chewing ability and cognitive impairment in the rural elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;70:209-13 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28214402.

- 13.Kim MS, et al. The association between mastication and mild cognitive impairment in Korean adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(23):e20653 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32502052.

- 14.Cardoso MG, et al. Relationship between functional masticatory units and cognitive impairment in elderly persons. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(5):417-23 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30614023.

- 15.Popovac A, et al. Oral health status and nutritional habits as predictors for developing alzheimer’s disease. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(5):448-54 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34348313.

- 16.Park T, et al. More teeth and posterior balanced occlusion are a key determinant for cognitive function in the elderly. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33669490.

- 17.Lin CS, et al. Association between tooth loss and gray matter volume in cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14(2):396-407 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32170642.

- 18.Kumar S, et al. Oral health status and treatment need in geriatric patients with different degrees of cognitive impairment and dementia: a cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(6):2171-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34322409.

- 19.Delwel S, et al. Chewing efficiency, global cognitive functioning, and dentition: A cross-sectional observational study in older people with mild cognitive impairment or mild to moderate dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:225 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33033478.

- 20.Da Silva JD, et al. Association between cognitive health and masticatory conditions: a descriptive study of the national database of the universal healthcare system in Japan. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13(6):7943-52 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33739304.

- 21.Galindo-Moreno P, et al. The impact of tooth loss on cognitive function. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26(4):3493-500 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34881401.

- 22.Stewart R, et al. Adverse oral health and cognitive decline: The health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):177-84 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23405916.

- 23.Dintica CS, et al. The relation of poor mastication with cognition and dementia risk: A population-based longitudinal study. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(9):8536-48 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32353829.

- 24.Kim MS, Han DH. Does reduced chewing ability efficiency influence cognitive function? Results of a 10-year national cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(25):e29270 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35758356.

- 25.Ko KA, et al. The Impact of Masticatory Function on Cognitive Impairment in Older Patients: A Population-Based Matched Case-Control Study. Yonsei Med J. 2022;63(8):783-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35914761.

- 26.Garre-Olmo J. [Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias]. Rev Neurol. 2018;66(11):377-86 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29790571.

- 27.Stephan BCM, et al. Secular Trends in Dementia Prevalence and Incidence Worldwide: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(2):653-80 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30347617.

- 28.Lopez OL, Kuller LH. Epidemiology of aging and associated cognitive disorders: Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;167:139-48 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31753130.

- 29.Ono Y, et al. Occlusion and brain function: mastication as a prevention of cognitive dysfunction. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(8):624-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20236235.

- 30.Kubo KY, et al. Masticatory function and cognitive function. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2010;87(3):135-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21174943.

- 31.Chen H, et al. Chewing Maintains Hippocampus-Dependent Cognitive Function. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12(6):502-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26078711.

- 32.Azuma K, et al. Association between Mastication, the Hippocampus, and the HPA Axis: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(8) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28771175.

- 33.Chuhuaicura P, et al. Mastication as a protective factor of the cognitive decline in adults: A qualitative systematic review. Int Dent J. 2019;69(5):334-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31140598.

- 34.Lopez-Chaichio L, et al. Oral health and healthy chewing for healthy cognitive ageing: A comprehensive narrative review. Gerodontology. 2021;38(2):126-35 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33179281.

- 35.Tada A, Miura H. Association between mastication and cognitive status: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;70:44-53 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28042986.

- 36.Ahmed SE, et al. Influence of Dental Prostheses on Cognitive Functioning in Elderly Population: A Systematic Review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2021;13(Suppl 1):S788-S94 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34447202.

- 37.Tonsekar PP, et al. Periodontal disease, tooth loss and dementia: Is there a link? A systematic review. Gerodontology. 2017;34(2):151-63 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28168759.

- 38.Nangle MR, Manchery N. Can chronic oral inflammation and masticatory dysfunction contribute to cognitive impairment? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2020;33(2):156-62 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31895157.

- 39.Nakamura T, et al. Oral dysfunctions and cognitive impairment/dementia. J Neurosci Res. 2021;99(2):518-28 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33164225.

- 40.Weijenberg RAF, et al. Mind your teeth-The relationship between mastication and cognition. Gerodontology. 2019;36(1):2-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30480331.

- 41.Asher S, et al. Periodontal health, cognitive decline, and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(9):2695-709 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36073186.

- 42.Lin CS. Revisiting the link between cognitive decline and masticatory dysfunction. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29304748.

- 43.Wu YT, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time – current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(6):327-39 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28497805.

- 44.National Psoriasis Foundation. Soriatane (Acitretin). https://www.psoriasis.org/soriatane-acitretin/.

- 45.National Psoriasis Foundation. Current Biologics on the Market. https://www.psoriasis.org/current-biologics-on-the-market/.

- 46.Dalmády S, Kemény L, Antal M, Gyulai R. Periodontitis: a newly identified comorbidity in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2020;16(1):101-8. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1700113.

- 47.Mickenautsch S, Yengopal V. Effect of xylitol versus sorbitol: a quantitative systematic review of clinical trials. Int Dent J 2012;62(4):175-88.

- 48.Rethman MP, Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Billings RJ, Burne RA, Clark M, Donly KJ, Hujoel PP, Katz BP, Milgrom P, Sohn W, Stamm JW, Watson G, Wolff M, Wright T, Zero D, Aravamudhan K, Frantsve-Hawley J, Meyer DM; for the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs Expert Panel on Nonfluoride Caries-Preventive Agents. Nonfluoride caries-preventive agents. Executive summary of evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc 2011;142(9):1065-71.

- 49.Milgrom P, Söderling EM, Nelson S, Chi DL, Nakai Y. Clinical evidence for polyol efficacy. Adv Dent Res 2012; 24(2):112-6.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Fiona-Collins-thumbnail-1-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Ira-Lamster-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2018/07/The-Dangers-of-Sugar-2.jpg)