Preventive Dentistry How do Dentists Manage Dentinal Hypersensitivity?

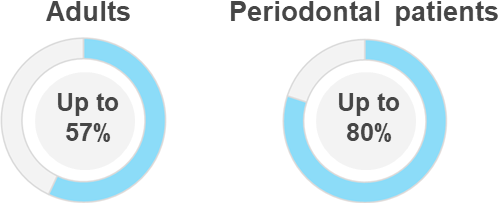

Dentinal hypersensitivity (DH) is a general term for sharp oral pain of short duration in response to stimuli at sites with exposed dentin, which cannot be explained by any other condition.1Holland GR, Narhi MN, Addy M, Gangarosa, Orchardson R. Guidelines for the design and conduct of clinical trials on dentine hypersensitivity. J Clin Periodontol 1997;24:808-13.,2Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:221-6. The stimulus triggering pain can be thermal (typically cold foods/drinks or breathing in cold air), osmotic change, evaporation (use of an air syringe), tactile or exposure to acidic or sweet substances.3Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Meyerowitz C, Litaker MS, Chonowski S, Heft MW, Gordan VV, Yardic RL, Madden TE, Reyes SC, Gilbert GH, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Management of dentin hypersensitivity by national dental practice-based research network practitioners: results from a questionnaire administered prior to initiation of a clinical study on this topic. BMC Oral Health 2017;17(1):41. (Figure 1) DH is a common problem among adults, and is familiar to dental providers. The reported prevalence of DH ranges from less than 5% to up to 57%.3Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Meyerowitz C, Litaker MS, Chonowski S, Heft MW, Gordan VV, Yardic RL, Madden TE, Reyes SC, Gilbert GH, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Management of dentin hypersensitivity by national dental practice-based research network practitioners: results from a questionnaire administered prior to initiation of a clinical study on this topic. BMC Oral Health 2017;17(1):41.,4Rees JS. The prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity in general dental practice in the UK. J Clin Periodontol 2000; 27:860-5. Among periodontal patients, higher prevalences of up to 80% have been reported after periodontal therapy.5Chabanski MG, Gillam DG, Bulman JS, Newman HN. Clinical evaluation of cervical dentine sensitivity in a population of patients referred to a specialist periodontology department: a pilot study. J Oral Rehab 1997;24:666-72.,6Lin YH, Gillam DG. The prevalence of root sensitivity following periodontal therapy: A systematic review. Int J Dent 2012;article ID 407023. Available at: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijd/2012/407023/. Overall, the incidence of DH is believed to be between 10% and 30% in the majority of populations.7Bartold PM. Dentinal hypersensitivity: A review. Austr Dent J 2006;51(3):212-8. (Figure 2) The management of DH involves the removal/reduction, where possible, of predisposing factors, and treatment with home use products and/or in-office treatments.

Figure 1.

Triggers for dentin hypersensitivity

Figure 2.

Reported prevalence of dentinal hypersensitivity3Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Meyerowitz C, Litaker MS, Chonowski S, Heft MW, Gordan VV, Yardic RL, Madden TE, Reyes SC, Gilbert GH, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Management of dentin hypersensitivity by national dental practice-based research network practitioners: results from a questionnaire administered prior to initiation of a clinical study on this topic. BMC Oral Health 2017;17(1):41.,4Rees JS. The prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity in general dental practice in the UK. J Clin Periodontol 2000; 27:860-5.,5Chabanski MG, Gillam DG, Bulman JS, Newman HN. Clinical evaluation of cervical dentine sensitivity in a population of patients referred to a specialist periodontology department: a pilot study. J Oral Rehab 1997;24:666-72.,6Lin YH, Gillam DG. The prevalence of root sensitivity following periodontal therapy: A systematic review. Int J Dent 2012;article ID 407023. Available at: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijd/2012/407023/.

Etiology of DH

In order for DH to occur, dentin must be exposed, and open dentinal tubules must be present. These open tubules provide a pathway between the intraoral environment and the dental pulp.7Bartold PM. Dentinal hypersensitivity: A review. Austr Dent J 2006;51(3):212-8. Dentin may become exposed following gingival recession, often due to excessive and improper toothbrushing, and following resective periodontal surgery.8Addy M. Dentine hypersensitivity: New perspectives on an old problem. Int Dent J 2002; 52:375-6.,9Drisko CH. Dentine hypersensitivity—Dental hygiene and periodontal considerations. Int Dent J 2002;52:385-93. Gingival recession may also be related to anatomic positioning in the dental arch, e.g., teeth positioned in a buccal direction, as well as inadequate attached gingiva, loss of attachment, and use of smokeless tobacco10Montén U, Wennstrom JL, Ramberg P. Periodontal conditions in male adolescents using smokeless tobacco (moist snuff). J Clin Periodontol 2006;33:863-8.. Following gingival recession, the thin layer of cementum covering dentin is easily lost. This may occur during periodontal debridement and restorative care. Loss of enamel and cementum exposes dentin and can be the result of abrasion, attrition, erosion, or a combination of these processes.2Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:221-6.,7Bartold PM. Dentinal hypersensitivity: A review. Austr Dent J 2006;51(3):212-8.,11Arambawatta K, Peiris R, Nanayakkara D. Morphology of the cemento-enamel junction in premolar teeth. J Oral Sci 2009;51(4):623-7. During tooth development, a gap can be present between the enamel and cementum, with the result that dentin will be exposed following tooth eruption. This is estimated to occur in approximately 10% of individuals.7Bartold PM. Dentinal hypersensitivity: A review. Austr Dent J 2006;51(3):212-8. Abfraction (proposed to be due to shearing off of tooth structure along the cemento-enamel junction) has also been suggested as a potential cause of DH, however there is considerable debate on the concept and theory of abfraction.2Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:221-6.,7Bartold PM. Dentinal hypersensitivity: A review. Austr Dent J 2006;51(3):212-8.,12Litonjua LA, Andreana S, Patra AK, Cohen RE. An assessment of stress analyses in the theory of abfraction. Biomed Mater Eng 2004;14(3):311-21. Further, the smear layer that usually covers the dentin, and that contains debris from abraded dentin, is removed by acids and excessive toothbrushing. In addition, prophylaxis and periodontal debridement remove the smear layer, and can increase DH following treatment. Transient DH may also occur during tooth whitening. (Table 1)

Brannstrӧm’s hydrodynamic theory is widely-recognized as the mechanism responsible for DH.13Brännström M. Dentin sensitivity and aspiration of odontoblasts. J Am Dent Assoc 1963; 66:366-70.,14Cummins D. Dentin hypersensitivity: From diagnosis to a breakthrough therapy for everyday sensitivity relief. J Clin Dent 2009;19(1; Spec Iss):1-9. This theory proposes that a stimulus triggers an increase in fluid flow or a change in the direction of fluid within open dentinal tubules, causing an electrical discharge as well as a change in pressure that stimulates myelinated A-fibers adjacent to the odontoblasts.2Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:221-6.,8Addy M. Dentine hypersensitivity: New perspectives on an old problem. Int Dent J 2002; 52:375-6.,15Trowbridge HO. Review of dental pain—histology and physiology. J Endod 1986;12(10):445-52. Neural transmission of this signal to the brain is interpreted as pain. The hydrodynamic theory is also supported by an investigation using scanning electron microscopy.16Absi EG, Addy M, Adams D. Dentine hypersensitivity. A study of the patency of dentinal tubules in sensitive and non‐sensitive cervical dentine. J Clin Periodontol 1997;14(5):280-4. Teeth with DH were found to have an approximately eight-fold number of dentinal tubules for a given area, and a two-fold increase in tubule diameter, compared to teeth without DH. Based on this, it is estimated that fluid flow increases by a factor 100.2Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:221-6. Further, increased amounts of methylene blue dye were able to penetrate teeth with DH, and to greater depths, than in teeth without DH.16Absi EG, Addy M, Adams D. Dentine hypersensitivity. A study of the patency of dentinal tubules in sensitive and non‐sensitive cervical dentine. J Clin Periodontol 1997;14(5):280-4.

| Table 1. Etiology of DH |

|---|

| Loss of enamel or/and cementum • Abrasion, attrition or erosion • Combinations of the above • Possibly abfraction? |

| Loss of cementum • Debridement, restorative care |

| Gap between enamel and cementum |

| Removal of smear layer • Prophylaxis, debridement, excessive toothbrushing, erosion |

| Tooth whitening (transient DH) |

Diagnosis by Exclusion

A diagnosis by exclusion is required for DH. Oral conditions including dental caries, fractured restorations, marginal leakage, post-operative sensitivity, cracked tooth syndrome, fractured teeth, palatogingival grooves, reversible/irreversible pulpitis, gingival inflammation, and trauma must be ruled out before a diagnosis of DH is made.2Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:221-6.,8Addy M. Dentine hypersensitivity: New perspectives on an old problem. Int Dent J 2002; 52:375-6. (Table 2)

| Table 2. Differential Diagnosis |

|---|

| • Dental caries • Cracked tooth syndrome • Fractured tooth • Fractured restorations • Marginal leakage • Post-operative sensitivity • Pulpitis • Palatogingival grooves • Gingival inflammation • Trauma |

The results of one study indicated that 99% of clinicians used multiple approaches to exclude other causes of oral pain and to identify DH.3Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Meyerowitz C, Litaker MS, Chonowski S, Heft MW, Gordan VV, Yardic RL, Madden TE, Reyes SC, Gilbert GH, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Management of dentin hypersensitivity by national dental practice-based research network practitioners: results from a questionnaire administered prior to initiation of a clinical study on this topic. BMC Oral Health 2017;17(1):41. The most common choice was a spontaneous patient report followed by clinical examination (48%). In addition, 26%, 12% and 6% of clinicians, respectively, reported applying a blast of air from an air syringe, contacting dentin with a dental explorer, and asking patients about DH and patients then reporting it. A further 4% and 2% of clinicians indicated use of endo-ice spray and application of cold water, respectively.3Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Meyerowitz C, Litaker MS, Chonowski S, Heft MW, Gordan VV, Yardic RL, Madden TE, Reyes SC, Gilbert GH, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Management of dentin hypersensitivity by national dental practice-based research network practitioners: results from a questionnaire administered prior to initiation of a clinical study on this topic. BMC Oral Health 2017;17(1):41. (Figure 3) Predisposing factors such as gingival recession, ingestion of acidic drinks/foods, bulimia, GERD, and bruxism should also be considered during the investigation and diagnostic process.

Figure 3.

Approaches used by clinicians during the diagnosis of DH

Management and Treatment Approaches for DH

Elimination of predisposing factors together with active treatment should be used as part of the management of DH, to help ensure successful outcomes.2Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:221-6. As appropriate, patients should be given dietary advice, oral hygiene instructions, treated for predisposing factors, and referred for treatment of medical conditions (e.g., bulimia or GERD).

There are two basic approaches to the treatment of DH, which include a wide range of topical, restorative and surgical options. The first approach is the use of desensitizing agents that permeate the dentinal tubules and block transmission of neural signals to the brain, thereby preventing/reducing the pain sensation.17Ajcharanukul O, Kraivaphan P, Wanachantararak S, Vongsavan N, Matthews B. Effects of potassium ions on dentine sensitivity in man. Arch Oral Biol 2007;52:632–9. Typically, a desensitizing toothpaste containing 5% potassium nitrate is used. In some countries, other options include potassium chloride and potassium citrate formulations. In one review, efficacy was demonstrated for potassium nitrate, however it was noted that due to the small number of subjects and variability in assessment methods for DH the evidence was weak.18Poulsen S, Errboe M, Lescay Mevil Y, Glenny AM. Potassium containing toothpastes for dentine hypersensitivity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD001476. In a second review, the evidence supported the efficacy of potassium-containing dentifrice formulations, while in a third review all potassium-containing desensitizing toothpaste formulations were found to be effective in reducing DH triggered by air and tactile stimuli, as well as reducing self-reported DH.14Cummins D. Dentin hypersensitivity: From diagnosis to a breakthrough therapy for everyday sensitivity relief. J Clin Dent 2009;19(1; Spec Iss):1-9.,19Orchardson R, Gillam DG. The efficacy of potassium salts as agents for treating dentin hypersensitivity. J Orofac Pain 2000;14(1):9-19.

The second approach uses agents/techniques that occlude the dentinal tubules and/or form a smear layer or barrier over the exposed dentin. Home care products found to be effective include 0.4% stannous fluoride toothpaste and gel formulations, calcium-containing and silica-containing pastes and gels, arginine/calcium carbonate formulations, stannous fluoride rinses and oxalates.2Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:221-6.,20Thrash WJ, Dodds MW, Jones DL. The effect of stannous fluoride on dentinal hypersensitivity. Int Dent J 1994;44 (Suppl):107-18.,21Schiff T, Saletta L, Baker RA, Winston JL, He T. Desensitizing effect of a stabilized stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2005;26(Suppl):35-40.,22Yang ZY, Wang F, Lu K, Li YH, Zhou Z. Arginine-containing desensitizing toothpaste for the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity: a meta-analysis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2016;8:1-14.,23Lopes AO, Aranha AC. Comparative evaluation of the effects of Nd:YAG laser and a desensitizer agent on the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity: a clinical study. Photomed Laser Surg 2013;31(3):132-8. In-office treatments providing relief from hypersensitivity include fluoride varnishes, 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA), glutaraldehyde/HEMA, oxalates, calcium-containing gels, placement of sealants or restorative materials, laser therapy and, in some cases, free gingival grafts that cover an area of gingival recession associated with exposed dentin and DH.2Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:221-6.,7Bartold PM. Dentinal hypersensitivity: A review. Austr Dent J 2006;51(3):212-8.,24Yilmaz NA, Ertas E, Orucoğlu H. Evaluation of five different desensitizers: A comparative dentin permeability and SEM investigation in vitro. Open Dent J 2017;11:15-33.,25Schmidlin PR, Sahrmann P. Current management of dentin hypersensitivity. Clin Oral Investig 2013;17(Suppl 1):55-9.,26Özcan E, Çakmak M, Ersahan S. Free gingival graft in the treatment of Class II gingival recession defects and its effects on dentin desensitization. Clin Dent Res 2012;36(3):10-5.

Clinicians’ Choices in the Treatment of DH

Given the range of options available for the treatment of DH, it is illustrative to review how dental professionals treat patients with DH. A report of findings from the National (United States) Dental Practice-Based Research Network examined how dentists manage DH. Eighty-six percent of respondents (n=188) reported routinely using multiple approaches.3Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Meyerowitz C, Litaker MS, Chonowski S, Heft MW, Gordan VV, Yardic RL, Madden TE, Reyes SC, Gilbert GH, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Management of dentin hypersensitivity by national dental practice-based research network practitioners: results from a questionnaire administered prior to initiation of a clinical study on this topic. BMC Oral Health 2017;17(1):41. The most frequently reported products were fluoride formulations and desensitizing toothpastes containing potassium nitrate, used by 97% and 94% of clinicians, respectively. Further, 64%, 52%, 42%, 16% and 3% reported using restorative materials, bonding agents, glutaraldehyde/HEMA products, sealants and lasers, respectively. Oxalates were used by 11% of clinicians. (Figure 4) The first choices for treatment were reported to be potassium nitrate toothpaste and fluoride formulations for 48% and 38% of clinicians, respectively.3Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Meyerowitz C, Litaker MS, Chonowski S, Heft MW, Gordan VV, Yardic RL, Madden TE, Reyes SC, Gilbert GH, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Management of dentin hypersensitivity by national dental practice-based research network practitioners: results from a questionnaire administered prior to initiation of a clinical study on this topic. BMC Oral Health 2017;17(1):41.

A second report used a questionnaire and a stylized case to examine treatment approaches for DH.27Clark D, Levin L. Tooth hypersensitivity treatment trends among dental professionals. Quintessence Int 2018;49(2):147-51. The preferred approaches reported by clinicians were the application of topical agents (41%) and use of desensitizing toothpastes (39%). As second-line treatments, respondents listed tooth restoration (29%) and gingival grafting (8%) as approaches. The authors concluded that practitioners utilized aggressive treatments, i.e., tooth restoration and gingival grafting, too early in the treatment of DH, and emphasized the need to approach treatment of DH in a conservative manner. In a review on the management of DH by the same authors, it was concluded that invasive treatment should only be considered after the range of nonsurgical approaches has been tried.28Clark D, Levin L. Non-surgical management of tooth hypersensitivity. Int Dent J 2016;66(5):249-56. In cases where significant amounts of tooth structure have been lost, restorative care may be the preferred approach due to the need to restore tooth structure for function and esthetics in addition to treating DH.

Figure 4.

Frequently reported products used to treat DH

Conclusions

DH is a frequent concern for patients and needs to be identified and diagnosed by a process of exclusion. As part of the management of DH, where possible, predisposing factors should be addressed. Treatment approaches include over-the-counter desensitizing toothpastes, other home use products and in-office treatments. It is recommended that brushing twice-daily with a desensitizing toothpaste should be the first choice for treatment.2Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:221-6. Desensitizing toothpastes are readily available, inexpensive, noninvasive, and typically contain fluoride for an anti-caries benefit. Invasive treatments should be reserved for cases that remain unresolved following noninvasive approaches.28Clark D, Levin L. Non-surgical management of tooth hypersensitivity. Int Dent J 2016;66(5):249-56.In addition, the development of new and non-invasive approaches to treat DH is warranted because as populations retain more teeth throughout adulthood, the problem of DH is expected to increase.29Olley RC, Sehmi H. The rise of dentine hypersensitivity and tooth wear in an ageing population. Br Dent J 2017;223(4):293-7.

References

- 1.Porter SR, Scully C. Oral malodour (halitosis). Br Med J 2006;333:632-5.

- 2.Settineri S, Mento C, Gugliotta SC, Saitta A, Terranova A, Trimarchi G, Mallamace D. Self-reported halitosis and emotional state: impact on oral conditions and treatments. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:34.

- 3.De Boever EH, De Uzeda M, Loesche WJ. Relationship between volatile sulfur compounds, BANA-hydrolyzing bacteria and gingival health in patients with and without complaints of oral malodor. J Clin Dent 1994;4(4):114-9.

- 4.Kleinberg I, Wolff MS, Codipilly DM. ADA Role of saliva in oral dryness, oral feel and oral malodour. Int Dent J 2002;52 (Suppl 3):236‑40.

- 5.American Dental Association. Bad breath. Causes and tips for controlling it. J Am Dent Assoc 2012;143(9):1053.

- 6.Quirynen M, Dadamio J, Van den Velde S, De Smit M, Dekeyser C, Van Tornout M and Vanderkerckhove B. Characteristics of 2000 patients who visited a halitosis clinic. J Clin Periodontol 2009;36:970–5.

- 7.De Geest S, Laleman I, Teughels W, Dekeyser C, Quirynen M. Periodontal diseases as a source of halitosis: a review of the evidence and treatment approaches for dentists and dental hygienists. Periodontol 2016;71:213-27.

- 8.Scully C, Felix DH. Oral medicine – update for the dental practitioner: Oral malodour. Br Dent J 2005;199:498‑500.

- 9.Youngnak-Piboonratanakit P, Vachirarojpisan T. Prevalence of self-perceived oral malodor in a group of Thai dental patients. J Dent (Tehran) 2010;7(4):196–204.

- 10.Hughes FJ, McNab R. Oral malodour–a review. Arch Oral Biol 2008;53 (Suppl 1):S1-7.

- 11.Sikorska-Zuk M, Bochnia M. Halitosis in children with adenoid hypertrophy. J Breath Res 2018;12(2):026011.

- 12.Struch F, Schwahn C, Wallaschofski H, Grabe HJ, Volzke H, Lerch MM, Meisel P, Kocher T. Self-reported halitosis and gastro-esophageal reflux disease in the general population. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23(3):260-6.

- 13.Yaegaki K, Coil JM. Examination, classification, and treatment of halitosis; clinical perspectives. J Can Dent Assoc 2000;66(5):257-61.

- 14.Seemann R, Conceicao MD, Filippi A, Greenman J, Lenton P, Nachnani S, Quirynen M, Roldan S, Schulze H, Sterer N, Tangerman A, Winkel EG, Yaegaki K, Rosenberg M. Halitosis management by the general dental practitioner—results of an international consensus workshop. J Breath Res 2014;8:017101.

- 15.Soder B, Johansson B, Soder PO. The relation between foetor ex ore, oral hygiene and periodontal disease. Swed Dent J 2000;24:73-82.

- 16.Hammad MM, Darwazeh AM, Al-Waeli H, Tarakji B, Alhadithy TT. Prevalence and awareness of halitosis in a sample of Jordanian population. J Int Soc Prev Commun Dent 2014;4:S178-86.

- 17.Rösing CK, Loesche W. Halitosis: an overview of epidemiology, etiology and clinical management. Braz Oral Res 2011;25(5):466-71.

- 18.Bornstein MM, Kislig K, Hoti BB, Seemann R, Lussi A. Prevalence of halitosis in the population of the city of Bern, Switzerland: A study comparing clinical and self-reported data. Eur J Oral Sci 2009;117:261-7.

- 19.Silva MF, Leite FRM, Ferreira LB, Pola NM, Scannapieco FA, Demarco FF, Nascimento GG. Estimated prevalence of halitosis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2018;22(1):47-55.

- 20.Romano F, Pigella E, Guzzi N, Aimetti M. Patients’ self-assessment of oral malodour and its relationship with organoleptic scores and oral conditions. Int J Dent Hyg 2010;8(1):41-6.

- 21.Al-Ansari JM, Boodai H, Al-Sumait N, Al-Khabbaz AK, Al-Shammari KF, Salako N. Factors associated with self-reported halitosis in Kuwaiti patients. J Dent 2006;34(7):444-9.

- 22.Nadanovsky P, Carvalho LB, Ponce de Leon A. Oral malodour and its association with age and sex in a general population in Brazil. Oral Dis 2007;13(1):105-9.

- 23.Almas K, Al-Hawish A, Al-Khamis W. Oral hygiene practices, smoking habit, and self-perceived oral malodor among dental students. J Contemp Dent Pract 2003;4(4):77-90.

- 24.Nalcaci R, Baran I. Factors associated with self-reported halitosis (SRH) and perceived taste disturbance (PTD) in elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2008;46(3):307-16.

- 25.de Jongh A, van Wijk AK, Horstman M, de Baat C. Self-perceived halitosis influences social interactions. BMC Oral Health 2016;16:31.

- 26.Bin Mubayrik A, Al Hamdan R, Al Hadlaq EM, AlBagieh H, AlAhmed D, Jaddoh H, Demyati M, Shryei RA. Self-perception, knowledge, and awareness of halitosis among female university students. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2017;9:45-52.

- 27.Zaitsu T, Ueno M, Shinada K, Wright FA, Kawaguchi Y. Social anxiety disorder in genuine halitosis patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:94.

- 28.Lu HX, Chen XL, Wong M, Zhu C, Ye W. Oral health impact of halitosis in Chinese adults. Int J Dent Hyg 2016.

- 29.Troger B, Laranjeira de Almeida Jr H, Duquia RP. Emotional impact of halitosis. Trends Psych Psychother 2014;36(4):Porto Alegre.

- 30.Suzuki N, Yoneda M, Naito T, Iwamoto T, Hirofuji T. Relationship between halitosis and psychologic status. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008;106(4):542-7.

- 31.Vali A, Roohafza H, Keshteli AH, Afghari P, Javad Shirani M, Afshar H, Savabi O, Adibi P. Relationship between subjective halitosis and psychological factors. Int Dent J 2015;65(3):120-6.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Fiona-Collins-thumbnail-1-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Ira-Lamster-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2018/10/Preventive-Dentistry-How-do-Dentists-Manage-Dentinal-Hypersensitivity-2.jpg)