Management of post-treatment dental pain

Pain of dental and craniofacial origin, including post-treatment pain, adversely affects quality of life and often requires pharmacological management.1Avellaneda-Gimeno V, Figueiredo R, Valmaseda-Castellón E. Quality of life after upper third molar removal: A prospective longitudinal study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2017;22 (6):e759-66. Among dental professionals, opioid analgesics have typically been prescribed for acute pain following extraction of third molars and endodontic treatment.2Baker JA, Avorn J, Levin R, Bateman BT. Opioid prescribing after surgical extraction of teeth in Medicaid patients, 2000-2010. J Am Med Assoc 2016;315:1653-4.,3McCauley JL, Leite RS, Melvin CL, Fillingim RB, Brady KT. Dental opioid prescribing practices and risk mitigation strategy implementation: Identification of potential targets for provider-level intervention. Subst Abus 2016;37(1):9-14. However, the opioid abuse crisis has led to a re-evaluation of the use of narcotics for pain management. This issue is being addressed from a variety of perspectives, including prescription guidelines and policies. Recent reviews and individual studies have also evaluated the efficacy of non-opioid medications for the management of acute pain, with positive results.

Historical Opioid Prescribing Patterns for Pain Management

Figure 1. Use of analgesics for nontraumatic dental pain between 1997-2000 and 2003-20075Okunseri C, Okunseri E, Xiang Q, Thorpe JM, Szabo A. Prescription of opioid and non-opioid analgesics for dental care in emergency departments: Findings from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Public Health Dent 2014;74(4):283-92.

While primary care physicians have prescribed the majority of opioid prescriptions,4Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic–prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med 2015;49(3):409-13. opioid prescription rates were historically higher in dentistry than in primary care settings.4Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic–prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med 2015;49(3):409-13. One study found that 92% and 55% of dentists endorsed opioid prescriptions for post-treatment pain management after third molar extractions and endodontic treatment.3McCauley JL, Leite RS, Melvin CL, Fillingim RB, Brady KT. Dental opioid prescribing practices and risk mitigation strategy implementation: Identification of potential targets for provider-level intervention. Subst Abus 2016;37(1):9-14. However, opioid prescribing for patients with nontraumatic dental pain who visited emergency and outpatient departments in short-stay, general hospitals between 1997-2000 and 2003-2007 revealed a problem in non-dental settings.5Okunseri C, Okunseri E, Xiang Q, Thorpe JM, Szabo A. Prescription of opioid and non-opioid analgesics for dental care in emergency departments: Findings from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Public Health Dent 2014;74(4):283-92. More patients received oral analgesics over time, and with a 38% and 160% increase in the percentage of patients receiving opioids and combination agents, respectively. (Figure 1) Further, 50% of emergency visits between 2007 and 2010 to emergency and outpatient departments in general and short-stay hospitals for nontraumatic dental pain resulted in an opioid prescription.6Okunseri C, Dionne RA, Gordon SM, Okunseri E, Szabo A. Prescription of opioid analgesics for nontraumatic dental conditions in emergency departments. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;156:261-6.

Policies and Programs to Reduce Opioid Use and Abuse

Federal and state programs and policies introduced since 2010 to reduce opioid use and abuse have included prescribing guidelines for pain management, prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), the FDA opioid action plan and Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy for Extended Release and Long-Acting Opioid Analgesics (a federal program monitoring overuse of opioids, a reduction in opioid prescribing quotas, requirements for CE and state laws requiring insurance coverage for opioids with abuse-deterrent properties).7Pezalla EJ, Rosen D, Erensen JG, Haddox JD, Mayne TJ. Secular trends in opioid prescribing in the USA. J Pain Res 2017;10:383-7.

New extended-release opioids have also been approved and are designed to reduce the potential for abuse.7Pezalla EJ, Rosen D, Erensen JG, Haddox JD, Mayne TJ. Secular trends in opioid prescribing in the USA. J Pain Res 2017;10:383-7. In addition, the Surgeon’s General’s report addressed drug stewardship, and identification and referral of affected individuals for care.8Surgeon General’s Report. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Available at: https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/. More recently, in March 2018, the American Dental Association announced a policy that endorses compulsory CE for prescribers of opioids and other controlled substances, and a statutory limit on dosing with a maximum of 7 days for opioid prescriptions.9American Dental Association announces new policy to combat opioid epidemic. Policy supports mandates on opioid prescribing and continuing education. March 26, 2018. Available at: https://www.ada.org/en/press-room/news-releases/2018-archives/march/american-dental-association-announces-new-policy-tocombat-opioid-epidemic. (Table 1)

| Table 1. Policies and Programs to Reduce Opioid Use and Abuse |

|---|

| Prescribing guidelines for pain management |

| Prescription drug monitoring programs |

| FDA initiatives |

| Federal program monitoring overuse of opioids |

| Reductions in opioid prescribing quotas |

| Requirements for continuing education |

| State-mandated insurance coverage for abuse-deterrent opioids |

| Identification and referral of affected individuals for care |

| Limits on dosing and duration of opioid use |

Improvements in Prescribing Patterns

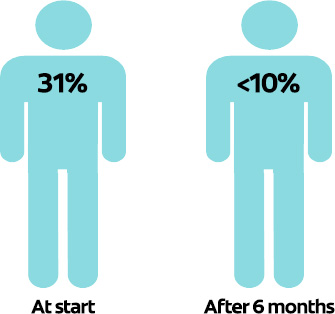

Prescribing patterns have improved since the introduction of these initiatives. From 2010 to 2012, only pain medicine, internal medicine and physical medicine/rehabilitation specialists continued to increase their opioid-prescribing rates. In the same period, prescribing rates declined by 5.7% in dentistry and 8.9% in emergency medicine, the largest declines by specific groups of health care professionals.4Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic–prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med 2015;49(3):409-13. PDMPs help providers identify patients with suspect prescription patterns, thwarting opioid diversion and abuse. In one location, after use of a PDMP become mandatory, the number of opioid prescriptions written by dentists dropped by 78% from 5,096 to 1,120 in a 3-month period, and from 31% to <10% of patients receiving opioids by the second 3-month period (p<0.05).10Rasubala L, Pernapati L, Velasquez X, Burk J, Ren Y-F. Impact of a mandatory prescription drug monitoring program on prescription of opioid analgesics by dentists. PLoS ONE 2015;10(8):e0135957. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Percentage of patients receiving an opioid prescription after implementation of a PDMP10Rasubala L, Pernapati L, Velasquez X, Burk J, Ren Y-F. Impact of a mandatory prescription drug monitoring program on prescription of opioid analgesics by dentists. PLoS ONE 2015;10(8):e0135957.

Management of Post-treatment Dental Pain using Non-opioid Oral Medications

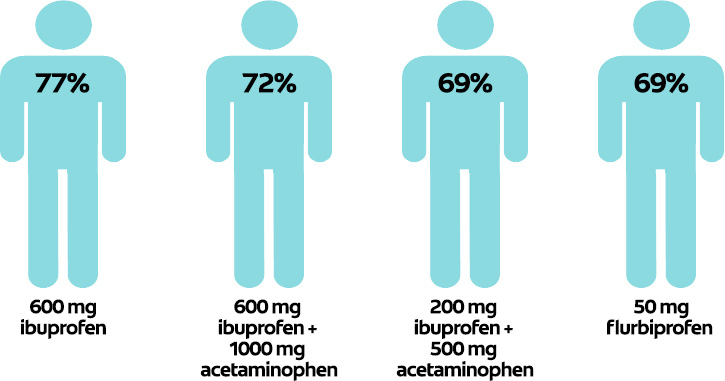

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are now considered first-line pain medications for the management of post-treatment dental pain and, barring contraindications, evidence supports ibuprofen as the preferred medication.11American Dental Association. Statement on the use of opioids in the treatment of dental pain. Available at: https://www.ada.org/en/about-the-ada/ada-positionspolicies-and-statements/policies-and-recommendations-onsubstance-use-disorders.,12Aminoshariae A, Kulild JC, Donaldson M, Hersh EV. Evidence based recommendations for analgesic efficacy to treat pain of endodontic origin. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Dent Assoc 2016;147(10):826-39.,13Huber MA, Terezhalmy GT. The use of COX-2 inhibitors for acute dental pain: A second look. J Am Dent Assoc 2006;137(4):480-7. In a recent systematic review of 27 randomized controlled trials, it was concluded that NSAIDs effectively manage pain related to endodontic treatment.12Aminoshariae A, Kulild JC, Donaldson M, Hersh EV. Evidence based recommendations for analgesic efficacy to treat pain of endodontic origin. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Dent Assoc 2016;147(10):826-39. In another review, 600 mg ibuprofen was found to result in at least 50% maximum pain relief in 77% of patients with moderate to severe post-treatment pain. This dosage was more effective than acetaminophen (paracetamol), and had similar adverse effects to placebo.14Moore P, Ziegler K, Lipman R, Aminoshariae A, Carrasco-Labra A, Mariotti A. Benefits and harms associated with analgesic medications used in the management of acute dental pain. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(4):256-65. Combinations of 400 mg ibuprofen plus 1,000 mg acetaminophen, 200 mg ibuprofen plus 500 mg acetaminophen, and 50 mg flurbiprofen were found to result in at least 50% maximum pain relief in 72%, 69% and 69% of patients, respectively. (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Percentage of individuals experiencing ≥50% maximum pain relief, by medication14Moore P, Ziegler K, Lipman R, Aminoshariae A, Carrasco-Labra A, Mariotti A. Benefits and harms associated with analgesic medications used in the management of acute dental pain. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(4):256-65.

In contrast, 600 mg ibuprofen and 600 mg plus 1000 mg acetaminophen were found to provide similar pain relief in a review of 15 studies.15Smith EA, Marshall JG, Selph SS, Barker DR, Sedgley CM. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for managing postoperative endodontic pain in patients who present with preoperative pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod 2017;43(1):7-15. Three other reviews found combinations of ibuprofen and acetaminophen to be more effective in managing acute pain than monotherapy.16Derry C, Derry S, Moore R. Single dose oral ibuprofen plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(6).,17Alexander L, Hall E, Eriksson L, Rohlin M. The combination of non-selective NSAID 400 mg and paracetamol 1000 mg is more effective than each drug alone for treatment of acute pain: a systematic review. Swed Dent J 2014;38(1):1-14.,18Bailey E, Worthington H, Coulthard P. Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth, a Cochrane systematic review. Br Dent J 2014;216(8):451-5. Compared to opioids, 200 mg ibuprofen plus 315 mg acetaminophen was found in another review to be effective for pain management following third molar extractions.19Moore PA, Hersh EV. Combining ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute pain management after third-molar extractions. Translating clinical research to dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(8):898-908. In addition, 100 mg caffeine added to 400 mg ibuprofen was found in a recent study to increase the efficacy of pain relief following extraction of third molars.20Weiser T, Richter E, Hegewisch A, Muse DD, Lange R. Efficacy and safety of a fixed-dose combination of ibuprofen and caffeine in the management of moderate to severe dental pain after third molar extraction. Eur J Pain 2017. doi:10.1002/ejp.1068 Conversely, the addition of codeine did not increase the efficacy of ibuprofen in a recent trial.21Best AD, De Silva RK, Thomson WM, Tong DC, Cameron CM, De Silva HL. Efficacy of codeine when added to paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ibuprofen for relief of postoperative pain after surgical removal of impacted third molars: a double-blinded randomized control trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017;75(10):2063-9.

Based on conclusions in a summary review of 5 systematic reviews, the evidence supports the use of NSAIDs, and NSAIDS plus acetaminophen, for optimal pain management, with the best risk-benefit profile.14Moore P, Ziegler K, Lipman R, Aminoshariae A, Carrasco-Labra A, Mariotti A. Benefits and harms associated with analgesic medications used in the management of acute dental pain. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(4):256-65. It should be noted that opioid medication is required when other medications fail to provide adequate pain management, as occurs in patients with oral mucositis.22Mirabile A, Airoldib M, Ripamontic C, Bolnerd A, Murphy B, Russif E, Numicog G, Licitrah L, Bossiha Head P. Pain management in head and neck cancer patients undergoing chemo-radiotherapy: Clinical practical recommendations. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016;99:100-6. Pain associated with oral mucositis is also relieved with use of other agents, including adjunctive gabapentin. Certain topical agents are also effective.22Mirabile A, Airoldib M, Ripamontic C, Bolnerd A, Murphy B, Russif E, Numicog G, Licitrah L, Bossiha Head P. Pain management in head and neck cancer patients undergoing chemo-radiotherapy: Clinical practical recommendations. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016;99:100-6.

Analgesics and pain assessment

Extraction of third molars is a main reason for use of analgesics, and it is generally accepted that self-reported pain is greatest on the day of extraction and decreases significantly on the following days.1Avellaneda-Gimeno V, Figueiredo R, Valmaseda-Castellón E. Quality of life after upper third molar removal: A prospective longitudinal study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2017;22 (6):e759-66. In one trial, dental patients used, on average, only 15 of 28 opioid pills prescribed.23Maughan BC, Hersh EV, Shofer FS, Wanner KJ, Archer E, Carrasco LR, Rhodes KV. Unused opioid analgesics and drug disposal following outpatient dental surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;168:328-34. In other studies, significantly fewer ibuprofen pills than recommended were consumed post-treatment by adults who had undergone third molar extractions and by children receiving extractions, and were again mainly used in the first 2 days post-treatment.1Avellaneda-Gimeno V, Figueiredo R, Valmaseda-Castellón E. Quality of life after upper third molar removal: A prospective longitudinal study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2017;22 (6):e759-66.,24Jensen B. Post-operative pain and pain management in children after dental extractions under general anaesthesia. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2012;13(3):119-25. Therefore, it is wise to limit the number of opioid pills per prescription and, when these are indicated, reducing the number of pills potentially remaining to avoid the risk of diversion, and to dispose of leftover pills appropriately.7Pezalla EJ, Rosen D, Erensen JG, Haddox JD, Mayne TJ. Secular trends in opioid prescribing in the USA. J Pain Res 2017;10:383-7.,25Shei A, Rice JB, Kirson NY, Bodnar K, Birnbaum HG, Holly P, Ben-Joseph R. Sources of prescription opioids among diagnosed opioid abusers. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31(4):779-84. Further, for all analgesics the lowest effective dose should be prescribed, and the agent used for the shortest period of time necessary. Reliable pain assessment is also needed for pain management and remains a challenge, in particular when treating young children.26Jayagopal A, Jaju RA, Tate A. The practice and perception of pain assessment in US pediatric dentistry residency programs. Pediatr Dent 2010;32(7):546-50. In addition, in one survey it was found that pain assessment does not occur at each appointment in all pediatric dentistry programs.26Jayagopal A, Jaju RA, Tate A. The practice and perception of pain assessment in US pediatric dentistry residency programs. Pediatr Dent 2010;32(7):546-50. Clinicians with fewer years of clinical experience have reported feeling unprepared to identify pain in pre-schoolers.27Daher A, Costa M, Costa LR. Factors associated with paediatric dentists' perception of dental pain in pre-schoolers: a mixed-methods study. Int J Paediatr Dent 2015;25(1):51-60.

Pre-procedural analgesics

Evidence is limited for the use of pre-procedural non-opioid analgesics as part of post-treatment pain management. In one systematic review, NSAIDs were found to be ineffective in reducing post-treatment pain associated with third molar extractions, other oral surgery, and periodontal and endodontic procedures.28Møiniche S, Kehlet H, Dahl JB. A qualitative and quantitative systematic review of preemptive analgesia for postoperative pain relief: the role of timing of analgesia. Anesthesiol 2002;96(3):725-41. In one study, 600 mg gabapentin or 8 mg lornoxicam taken prior to endodontic treatment effectively controlled post-treatment pain, and gabapentin was more effective than lornoxicam for up to 24 hours.29Işik B, Yaman S, Aktuna S, Turan A. Analgesic efficacy of prophylactic gabapentin and lornoxicam in preventing postendodontic pain. Pain Med 2014;15(12):2150-5. Premedication with 20 mg ketorolac or 30 mg prednisolone has also been found to be effective.30Praveen R, Thakur S, Kirthiga M. Comparative evaluation of premedication with ketorolac and prednisolone on postendodontic pain: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Endod 2017; 43(5):667-73.

The efficacy of premedication in children and adolescents is equivocal. In a review of 5 studies, it was unclear whether pre-treatment acetaminophen relieved post-treatment pain.31McCann C. Preoperative analgesia for children and adolescents to reduce pain associated with dental treatment. Evid Based Dent 2017;18(1):17-8. In a Cochrane review, any potential benefit of pre-procedural analgesics was unclear, although it was surmised that they might be beneficial prior to placement of orthodontic separators.32Ashley PF, Parekh S, Moles DR, Anand P, MacDonald LC. Preoperative analgesics for additional pain relief in children and adolescents having dental treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(8):CD008392. However, in one study, preprocedural ibuprofen was more effective than placebo in controlling post-treatment pain for the first 24 hours after pulpotomies and provision of stainless steel crowns.33Shafie L, Esmaili S, Parirokh M, Pardakhti A, Nakhaee N, Abbott PV, Bargh H. Efficacy of pre-medication with ibuprofen on post-operative pain after pulpotomy in primary molars. Iran Endod J 2018;13(2):216-20. In a randomized double blind trial involving children 6 to 12 years-of-age undergoing primary molar extraction, preoperative ibuprofen provided greater pain relief than acetaminophen at 15 minutes and 4 hours post-treatment.34Baygin O, Tuzuner T, Isik B, Kusgoz A, Tanriver M. Comparison of pre-emptive ibuprofen, paracetamol, and placebo administration in reducing post-operative pain in primary tooth extraction. Int J Paediatr Dent 2011;21(4):306-13.

New Legislation

On October 24th, 2018, H.R. 6, the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act, also referred to as the ‘opioid bill,’ was signed into law.35American Dental Association. ADA News. President signs opioids bill, making it law. Available at: https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2018-archive/october/president-signs-opioids-bill. This bill contains a multi-faceted approach to tackling the opioid crisis, many aspects of which are directly relevant to dentistry. Some of these include additional funding for CE on best practices in pain management, improvements to PDMPs, medication disposal initiatives including additional drug collection centers, development of evidence-based guidelines on opioid prescribing by indication, interprofessional collaboration (e.g., assistance with best practices in dental pain for emergency departments), and research into new pain management therapies. In the future, healthcare professionals will also be required to submit training certification on controlled substances. (Table 2)

| Table 2. Approaches included in the HR 6 legislation35American Dental Association. ADA News. President signs opioids bill, making it law. Available at: https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2018-archive/october/president-signs-opioids-bill. |

|---|

| Additional funding for CE on best practices in pain management |

| Improvements to PDMPs |

| Medication disposal initiatives, with added drug collection centers |

| Development of evidence-based guidelines on opioid prescribing by indication |

| Interprofessional collaboration |

| Research into new pain management therapies |

| Future requirement for healthcare professional certified training on controlled substances |

Conclusions

Recent initiatives, including the 2018 ADA policy and the recently-enacted legislation, should facilitate safe opioid prescribing and reductions in opioid use. The initial results are promising. Progress has been made in dentistry in reducing opioid prescriptions. In addition, PDMPs help to prevent drug diversion, as will drug disposal programs. In one report, a more than 20% increase in the percentage of patients disposing or intending to do so of leftover medication was achieved after patients received education on an accessible pharmacy-based drug disposal program.23Maughan BC, Hersh EV, Shofer FS, Wanner KJ, Archer E, Carrasco LR, Rhodes KV. Unused opioid analgesics and drug disposal following outpatient dental surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;168:328-34. Patient education on the risks associated with opioids and the efficacy of non-opioid analgesics is also needed.

NSAIDs are now considered first-line pain medications. The results for NSAID combination therapy, typically with acetaminophen, are also promising. However, combinations of NSAIDS and acetaminophen are not available in the US at this time. Medication selection for an individual patient must always consider its absolute and relative contraindications, potential side effects, adverse events and drug interactions. Patients must also receive information about these topics. Additional research has been recommended on combination therapies and pre-procedural analgesics, as well as on monotherapy with NSAIDS to determine the optimal dose, frequency and specific NSAID that optimizes pain management while minimizing the risk of adverse events.15Smith EA, Marshall JG, Selph SS, Barker DR, Sedgley CM. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for managing postoperative endodontic pain in patients who present with preoperative pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod 2017;43(1):7-15.,32Ashley PF, Parekh S, Moles DR, Anand P, MacDonald LC. Preoperative analgesics for additional pain relief in children and adolescents having dental treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(8):CD008392. In the meantime, increased continuing education and training on best practices in pain management and pain assessment, prescribing of non-opioid analgesics, and widespread implementation of legislation, policies and programs in the dental setting, will help to combat the opioid crisis.

References

- 1.Avellaneda-Gimeno V, Figueiredo R, Valmaseda-Castellón E. Quality of life after upper third molar removal: A prospective longitudinal study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2017;22 (6):e759-66.

- 2.Baker JA, Avorn J, Levin R, Bateman BT. Opioid prescribing after surgical extraction of teeth in Medicaid patients, 2000-2010. J Am Med Assoc 2016;315:1653-4.

- 3.McCauley JL, Leite RS, Melvin CL, Fillingim RB, Brady KT. Dental opioid prescribing practices and risk mitigation strategy implementation: Identification of potential targets for provider-level intervention. Subst Abus 2016;37(1):9-14.

- 4.Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic–prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med 2015;49(3):409-13.

- 5.Okunseri C, Okunseri E, Xiang Q, Thorpe JM, Szabo A. Prescription of opioid and non-opioid analgesics for dental care in emergency departments: Findings from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Public Health Dent 2014;74(4):283-92.

- 6.Okunseri C, Dionne RA, Gordon SM, Okunseri E, Szabo A. Prescription of opioid analgesics for nontraumatic dental conditions in emergency departments. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;156:261-6.

- 7.Pezalla EJ, Rosen D, Erensen JG, Haddox JD, Mayne TJ. Secular trends in opioid prescribing in the USA. J Pain Res 2017;10:383-7.

- 8.Surgeon General’s Report. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Available at: https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/.

- 9.American Dental Association announces new policy to combat opioid epidemic. Policy supports mandates on opioid prescribing and continuing education. March 26, 2018. Available at: https://www.ada.org/en/press-room/news-releases/2018-archives/march/american-dental-association-announces-new-policy-tocombat-opioid-epidemic.

- 10.Rasubala L, Pernapati L, Velasquez X, Burk J, Ren Y-F. Impact of a mandatory prescription drug monitoring program on prescription of opioid analgesics by dentists. PLoS ONE 2015;10(8):e0135957.

- 11.American Dental Association. Statement on the use of opioids in the treatment of dental pain. Available at: https://www.ada.org/en/about-the-ada/ada-positionspolicies-and-statements/policies-and-recommendations-onsubstance-use-disorders.

- 12.Aminoshariae A, Kulild JC, Donaldson M, Hersh EV. Evidence based recommendations for analgesic efficacy to treat pain of endodontic origin. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Dent Assoc 2016;147(10):826-39.

- 13.Huber MA, Terezhalmy GT. The use of COX-2 inhibitors for acute dental pain: A second look. J Am Dent Assoc 2006;137(4):480-7.

- 14.Moore P, Ziegler K, Lipman R, Aminoshariae A, Carrasco-Labra A, Mariotti A. Benefits and harms associated with analgesic medications used in the management of acute dental pain. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(4):256-65.

- 15.Smith EA, Marshall JG, Selph SS, Barker DR, Sedgley CM. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for managing postoperative endodontic pain in patients who present with preoperative pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod 2017;43(1):7-15.

- 16.Derry C, Derry S, Moore R. Single dose oral ibuprofen plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(6).

- 17.Alexander L, Hall E, Eriksson L, Rohlin M. The combination of non-selective NSAID 400 mg and paracetamol 1000 mg is more effective than each drug alone for treatment of acute pain: a systematic review. Swed Dent J 2014;38(1):1-14.

- 18.Bailey E, Worthington H, Coulthard P. Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth, a Cochrane systematic review. Br Dent J 2014;216(8):451-5.

- 19.Moore PA, Hersh EV. Combining ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute pain management after third-molar extractions. Translating clinical research to dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(8):898-908.

- 20.Weiser T, Richter E, Hegewisch A, Muse DD, Lange R. Efficacy and safety of a fixed-dose combination of ibuprofen and caffeine in the management of moderate to severe dental pain after third molar extraction. Eur J Pain 2017. doi:10.1002/ejp.1068

- 21.Best AD, De Silva RK, Thomson WM, Tong DC, Cameron CM, De Silva HL. Efficacy of codeine when added to paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ibuprofen for relief of postoperative pain after surgical removal of impacted third molars: a double-blinded randomized control trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017;75(10):2063-9.

- 22.Mirabile A, Airoldib M, Ripamontic C, Bolnerd A, Murphy B, Russif E, Numicog G, Licitrah L, Bossiha Head P. Pain management in head and neck cancer patients undergoing chemo-radiotherapy: Clinical practical recommendations. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016;99:100-6.

- 23.Maughan BC, Hersh EV, Shofer FS, Wanner KJ, Archer E, Carrasco LR, Rhodes KV. Unused opioid analgesics and drug disposal following outpatient dental surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;168:328-34.

- 24.Jensen B. Post-operative pain and pain management in children after dental extractions under general anaesthesia. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2012;13(3):119-25.

- 25.Shei A, Rice JB, Kirson NY, Bodnar K, Birnbaum HG, Holly P, Ben-Joseph R. Sources of prescription opioids among diagnosed opioid abusers. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31(4):779-84.

- 26.Jayagopal A, Jaju RA, Tate A. The practice and perception of pain assessment in US pediatric dentistry residency programs. Pediatr Dent 2010;32(7):546-50.

- 27.Daher A, Costa M, Costa LR. Factors associated with paediatric dentists' perception of dental pain in pre-schoolers: a mixed-methods study. Int J Paediatr Dent 2015;25(1):51-60.

- 28.Møiniche S, Kehlet H, Dahl JB. A qualitative and quantitative systematic review of preemptive analgesia for postoperative pain relief: the role of timing of analgesia. Anesthesiol 2002;96(3):725-41.

- 29.Işik B, Yaman S, Aktuna S, Turan A. Analgesic efficacy of prophylactic gabapentin and lornoxicam in preventing postendodontic pain. Pain Med 2014;15(12):2150-5.

- 30.Praveen R, Thakur S, Kirthiga M. Comparative evaluation of premedication with ketorolac and prednisolone on postendodontic pain: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Endod 2017; 43(5):667-73.

- 31.McCann C. Preoperative analgesia for children and adolescents to reduce pain associated with dental treatment. Evid Based Dent 2017;18(1):17-8.

- 32.Ashley PF, Parekh S, Moles DR, Anand P, MacDonald LC. Preoperative analgesics for additional pain relief in children and adolescents having dental treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(8):CD008392.

- 33.Shafie L, Esmaili S, Parirokh M, Pardakhti A, Nakhaee N, Abbott PV, Bargh H. Efficacy of pre-medication with ibuprofen on post-operative pain after pulpotomy in primary molars. Iran Endod J 2018;13(2):216-20.

- 34.Baygin O, Tuzuner T, Isik B, Kusgoz A, Tanriver M. Comparison of pre-emptive ibuprofen, paracetamol, and placebo administration in reducing post-operative pain in primary tooth extraction. Int J Paediatr Dent 2011;21(4):306-13.

- 35.American Dental Association. ADA News. President signs opioids bill, making it law. Available at: https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2018-archive/october/president-signs-opioids-bill.