A Mechanism to Explain How Periodontitis Can Affect Pregnancy Outcomes

The realization that the infection and resultant inflammatory response associated with periodontitis can adversely affect a number of systemic diseases and conditions has changed the narrative about the importance of identifying and treating oral diseases. These findings take on particular importance for certain patients at risk for or diagnosed with these medical conditions. While periodontitis has been identified as a potential risk factor for dozens of diseases and disorders, the strongest body of evidence is for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus and adverse pregnancy outcomes. These three conditions were the focus of the World Workshop in Periodontics in 2012, and adverse pregnancy outcomes differs from the other associations in that young women are potentially affected, and pregnancy is not “chronic” considering the 9-month gestation period1Ide M, Papapanou PN. Epidemiology of association between maternal periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes–systematic review. J Clin Periodontol 2013;40 Suppl 14:S181-194.. Further, the relationship of periodontitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes is one of the associations highlighted in a review of “Periodontal Medicine” during the past 100 years2Beck JD, Papapanou PN, Philips KH, Offenbacher S. Periodontal medicine: 100 years of progress. J Dent Res 2019;98:1053-1062..

The association of periodontitis and adverse health outcomes has been focused on hematogenous spread of specific periodontal bacterial pathogens and the contribution of the resultant local (periodontal) inflammatory response to the total systemic inflammatory burden2Beck JD, Papapanou PN, Philips KH, Offenbacher S. Periodontal medicine: 100 years of progress. J Dent Res 2019;98:1053-1062..

Reports that pregnant women with periodontitis were at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO) has generated significant interest. Among the adverse outcomes that have been studied are pre-labor/premature rupture of membranes, pre-term labor and delivery, low birthweight and spontaneous abortion. For purposes of discussion, these conditions will be grouped together and referred to as APO, which continues to be recognized as a global health problem of enormous significance. Though it is not easy to determine the global prevalence of ABO due to different definitions in different parts of the world, it is estimated that 11% of all births fall into this category3Vogel JP, Chawanpaiboon S, Moller AB, Watananirun K, Bonet M, Lumbiganon P. The global epidemiology of preterm birth. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;52:3-12. . The prevalence pf APO in the United States has changed little in the in the past 10-15 years and was 10% in 20184March of Dimes. 2019 March of Dimes Report Card: Preterm birth rates and grades by state. March of Dimes. Retrieved from https://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/MOD2019_REPORT_CARD_and_POLICY_ACTIONS_BOOKLETv72.pdf on February 20, 2020.. Many risk factors for APO have been identified, including both older and younger maternal age, diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, hypertension and cardiovascular disease, smoking and alcohol consumption, recreational drug use and low socioeconomic status5Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. The National Academies Collection: reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Behrman RE, Butler AS, eds. Preterm birth: causes, consequences and prevention. Washington (DC): National Academies Press, National Academy of Sciences; 2007.. Nevertheless, more than half of all cases of APO do not have an identifiable risk factor3Vogel JP, Chawanpaiboon S, Moller AB, Watananirun K, Bonet M, Lumbiganon P. The global epidemiology of preterm birth. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;52:3-12.. In addition to immediate post-partum complications such as immature lung development and the increased risk of infection, the consequences of APO can affected the health of the individual for life, and include neurodevelopmental deficits (cerebral palsy, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, visual impairment, anxiety and depression), as well as increased risk for chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and hypertension6Luu TM, Rehman Mian MO, Nuyt AM. Long-term impact of preterm birth: neurodevelopmental and physical health outcomes. Clin Perinatol 2017;44:305-314..

Historically, great interest in this association was generated by publication in 1996 of a study by Offenbacher and colleagues7Offenbacher S, Katz V, Fertik G, et al. Periodontal infection as a possible risk factor for preterm low birth weight. J Periodontol 1996;67 Suppl 10S:1103-1113.. They compared women who experienced an adverse outcome with a matched group of women who did not experience such an outcome. After controlling for known risk factors for APO (i.e. tobacco use, consumption of alcohol), periodontitis was a significant risk factor for these outcomes, with an odds ratio of 7.9. This report was followed by many other publications assessing this association. Subsequently, a summation of the available data was presented in systematic reviews, and ultimately by a publication that summarized these systemic reviews8Daalderop LA, Wieland BV, Tomsin K, et al. Periodontal disease and pregnancy outcomes: overview of systematic reviews. JDR Clin Trans Res 2018;3:10-27.. A total of 23 systematic reviews were included, which were published between 2002 and 2016, and these included from 3 to 45 original studies. The conclusions in the systemic review of the systemic reviews were:

- There were no reports linking periodontal disease or periodontal treatment with death of the mother, or perinatal mortality.

- Focusing on the systematic reviews that included the studies with a lower risk of bias, the following associations were observed between periodontitis and specific adverse outcomes:

- Preterm birth: relative risk = 1.6 (based on 17 publications with a total of 6,741 patients).

- Low birthweight: relative risk = 1.7 (based on 10 publications with a total of 5,693 patients).

- Pre-eclampsia: a condition seen in pregnant women, associated with hypertension and elevated levels of protein in the urine. Relative risk = 2.2 (based on 15 studies with a total of 5,111 patients)

- Preterm low birth weight: relative risk = 3.4 (based on 4 studies with a total of 2,263 patients).

- The authors also calculated estimates of the population-attributable fraction (EPAF) of the effect of periodontal disease on these adverse outcomes. Here the EPAF is the percentage of affected individuals whose condition is considered to be a due to the presence of periodontitis.

- Preterm birth: 5-38%

- Low birthweight: 6-41%

- Pre-eclampsia: 10-55%

The authors concluded that “pregnant women with periodontal disease are at increased risk of developing pre-eclampsia and delivering a preterm and/or low birthweight baby”. They urged dentists and obstetricians to be aware of this linkage, and that preventive strategies and appropriate treatments need to be developed.

The next question, which is of equal importance, addresses the effect of treating periodontal disease on the occurrence of these adverse outcomes. A review published in 2016 included 15 randomized controlled trials, with a total of 7,161 patients. Comparisons included more intense versus less intense periodontal treatment and periodontal treatment versus no treatment9Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Middleton P, Esposito M, Glenny AM. Treating periodontal disease for preventing adverse birth outcomes in pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD005297..

In general, the quality of the evidence was low, meaning that the evaluated studies contained flaws. Many of the studies did not consider all variables that have been associated with APO. Their conclusions were that no reduction in adverse outcomes were observed (i.e. preterm birth at <32 weeks, <35 weeks, <37 weeks) with the provision of conservative periodontal therapy, generally in the second trimester. They did conclude that there was evidence that periodontal therapy could decrease the occurrence of low birthweight babies. These authors argued for better studies that included both periodontal outcomes and obstetrical outcomes.

A systematic review of systematic reviews that examined the effect of periodontal treatment on adverse pregnancy outcomes was published in 2018. There were 18 systematic reviews of which 13 included a meta-analysis10Rangel-Rincon LJ, Vivares-Builes AM, Botero JE, Agudelo-Suarez AA. An umbrella review exploring the effect of periodontal treatment in pregnant women on the frequency of adverse obstetric outcomes. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2018;18:218-239.. While descriptive reviews suggested that periodontal therapy was associated with improved pregnancy outcomes, when considering those reviews with a meta-analysis (to gauge the magnitude of the effect), differences due to the periodontal treatment were not significant.

Taken together, the available evidence indicates a fascinating dichotomy. There is an association between the presence of periodontal disease/periodontitis and APO. However, treatment studies (with treatment generally provided in the second trimester) did not have a marked effected on these obstetrical outcomes. However, a recent report in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology may provide an explanation for this dichotomy11Fischer LA, Demerath E, Bittner-Eddy P, Costalonga M. Placental colonization with periodontal pathogens: the potential missing link. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:383-392 e383..

This review by Fischer and colleagues11Fischer LA, Demerath E, Bittner-Eddy P, Costalonga M. Placental colonization with periodontal pathogens: the potential missing link. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:383-392 e383. proposes a mechanistic explanation. They first emphasize that APO continues to be a global problem with life-long consequences for affected babies, as well as their family and society in general. These authors argue that the relationship between periodontitis and APO should not be dismissed because of the available clinical treatment data.

These authors emphasize the potential importance of periodontal bacteria that may be essential to the periodontitis-APO relationship, specifically Fusobacterium nucleatum and Porphyromonas gingivalis. F. nucleatum has been the microbiological focus of this relationship12Vander Haar EL, So J, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Han YW. Fusobacterium nucleatum and adverse pregnancy outcomes: epidemiological and mechanistic evidence. Anaerobe 2018;50:55-59.. They also include P. gingivalis since it possesses a range of virulence factors that may contribute to poor health outcomes.

They first address the key question of why conservative periodontal therapy trials failed to have a significant effect on improving pregnancy outcomes. These trials provided periodontal therapy during the second trimester. The treatment provided was scaling and root planing which disrupts the subgingival biofilm. As the treatment is provided to patients with evidence of periodontitis, tissue inflammation would very likely have been present prior to the second trimester, the sulcular epithelium would be ulcerated and the likelihood exists for hematogenous spread of the subgingival microorganisms to have occurred early in the pregnancy. Further, they note that microbiologically there are similarities between the microflora of the oral cavity and that of the placenta. Infection and subsequent inflammation of the urinary tract and vagina have been associated with APO, and both periodontitis and vaginosis are associated with developed of an anaerobic environment, which will favor colonization by pathogenic microflora. Colonization of the placenta by pathogenic bacteria leads to an inflammatory response, which is likely a key component of the periodontitis-APO relationship.

These authors also discuss how infection of the placenta by periodontal pathogenesis should be evaluated. Use of various laboratory approaches to identify the presence of the suspected pathogen (i.e. polymerase chain reaction) is likely inadequate. What must be determined is whether the organisms are just transient, or whether true infection has been established. Also questioned is how the placental samples are collected, and whether contamination of the samples occurred (for example by maternal blood), or even if sample processing may have contributed to a false positive reading.

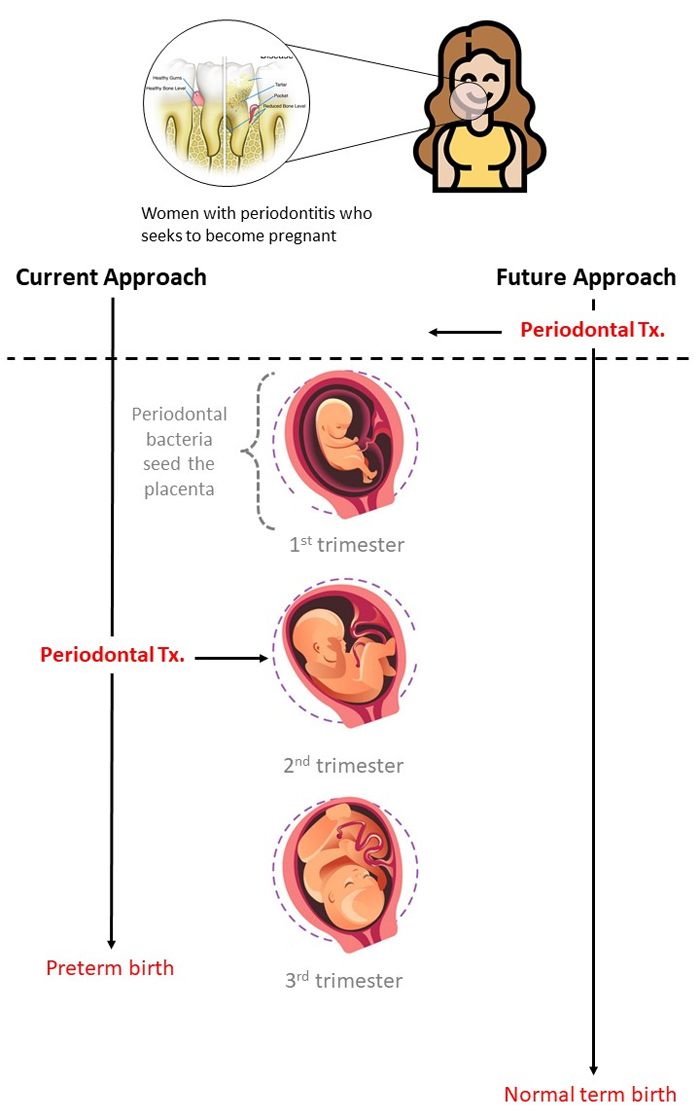

Figure 1.

Current and proposed approaches to reducing the risk of preterm birth associated with periodontitis

This review concludes with some important take-away messages.

- The placental environment and the periodontal environment have aspects in common, suggesting that periodontal microorganisms that enter the circulation and seed the placenta may find a niche that can support infection.

- The timing of the seeding of the placenta when periodontal pathogens are being assessed for their possible contribution to APO can be challenging to determine. Samples from the placenta are generally taken at the time of delivery, and therefore when infection occurred is not known. They suggest that seeding occurs in the first trimester, and therefore if a woman is considering becoming pregnant, and periodontitis is present, periodontal treatment should occur prior to the pregnancy (see Figure 1). An important consideration is the timing of periodontal treatment.

- The presence of periodontal bacteria (i.e. F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis) in the placenta does not in itself constitute evidence of cause and effect regarding APO. Rather, it is the number of bacteria (intensity of the infection) that is believed to be important.

- In the future, studies of this association need to be focused on careful collection of placental samples. These studies should also determine the intensity of the infection that would be associated with an adverse outcome. As noted, identification of periodontal bacteria is not in itself adequate evidence of cause and effect. A more detailed analysis is needed, which may mean identification of specific bacterial strains or other molecular characteristics associated with virulence. To further support a pathogenic association, samples from both the oral cavity and placenta should be collected to check for homology.

For dental clinicians, the following conclusions can be drawn, and applied to specific clinical situations:

- Woman who ask about the periodontitis-APO relationship, or are of child-bearing age can be told of an association between the presence of periodontitis and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

- Patients can be told that the published treatment studies, where periodontal therapy is provided to pregnant patients with periodontitis during the second trimester, have generally not reduced the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes. This treatment has generally improved the status of the periodontium, without adverse effects on the mother or fetus. Woman should be urged to maintain a healthy mouth during pregnancy, since pregnancy is often associated with increased inflammatory response in the periodontium13Gonzalez-Jaranay M, Tellez L, Roa-Lopez A, Gomez-Moreno G, Moreu G. Periodontal status during pregnancy and postpartum. PLoS One 2017;12:e0178234..

- Based on the review of Fischer and colleagues11Fischer LA, Demerath E, Bittner-Eddy P, Costalonga M. Placental colonization with periodontal pathogens: the potential missing link. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:383-392 e383., if possible, women of child-bearing age who are considering becoming pregnant and have evidence of periodontitis should be urged to have periodontal treatment before becoming pregnant. This represents something of a challenge, as there is evidence that pregnant women are not adequately familiar with the importance of oral health during pregnancy14Gaszynska E, Klepacz-Szewczyk J, Trafalska E, Garus-Pakowska A, Szatko F. Dental awareness and oral health of pregnant women in Poland. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2015;28:603-611.,15Togoo RA, Al-Almai B, Al-Hamdi F, Huaylah SH, Althobati M, Alqarni S. Knowledge of pregnant women about pregnancy gingivitis and children oral health. Eur J Dent 2019;13:261-270..

- There is a need for oral health care providers to communicate the periodontitis-APO relationship to other health professionals that care of women who are pregnant (obstetricians and midwives;16Boutigny H, de Moegen ML, Egea L, et al. Oral infections and pregnancy: knowledge of gynecologists/obstetricians, midwives and dentists. Oral Health Prev Dent 2016;14:41-47.).

References

- 1.Dominy SS, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv. 2019;5(1):eaau3333 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30746447.

- 2.Sadrameli M, et al. Linking mechanisms of periodontitis to Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020;33(2):230-8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32097126.

- 3.Borsa L, et al. Analysis the link between periodontal diseases and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34501899.

- 4.Costa MJF, et al. Relationship of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of pre-clinical studies. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(3):797-806 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33469718.

- 5.Munoz Fernandez SS, Lima Ribeiro SM. Nutrition and Alzheimer disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(4):677-97 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30336995.

- 6.Aquilani R, et al. Is the Brain Undernourished in Alzheimer’s Disease? Nutrients. 2022;14(9) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35565839.

- 7.Fukushima-Nakayama Y, et al. Reduced mastication impairs memory function. J Dent Res. 2017;96(9):1058-66 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28621563.

- 8.Kim HB, et al. Abeta accumulation in vmo contributes to masticatory dysfunction in 5XFAD Mice. J Dent Res. 2021;100(9):960-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33719684.

- 9.Miura H, et al. Relationship between cognitive function and mastication in elderly females. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30(8):808-11 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12880404.

- 10.Lexomboon D, et al. Chewing ability and tooth loss: association with cognitive impairment in an elderly population study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1951-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23035667.

- 11.Elsig F, et al. Tooth loss, chewing efficiency and cognitive impairment in geriatric patients. Gerodontology. 2015;32(2):149-56 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24128078.

- 12.Kim EK, et al. Relationship between chewing ability and cognitive impairment in the rural elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;70:209-13 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28214402.

- 13.Kim MS, et al. The association between mastication and mild cognitive impairment in Korean adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(23):e20653 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32502052.

- 14.Cardoso MG, et al. Relationship between functional masticatory units and cognitive impairment in elderly persons. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(5):417-23 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30614023.

- 15.Popovac A, et al. Oral health status and nutritional habits as predictors for developing alzheimer’s disease. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(5):448-54 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34348313.

- 16.Park T, et al. More teeth and posterior balanced occlusion are a key determinant for cognitive function in the elderly. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33669490.

- 17.Lin CS, et al. Association between tooth loss and gray matter volume in cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14(2):396-407 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32170642.

- 18.Kumar S, et al. Oral health status and treatment need in geriatric patients with different degrees of cognitive impairment and dementia: a cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(6):2171-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34322409.

- 19.Delwel S, et al. Chewing efficiency, global cognitive functioning, and dentition: A cross-sectional observational study in older people with mild cognitive impairment or mild to moderate dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:225 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33033478.

- 20.Da Silva JD, et al. Association between cognitive health and masticatory conditions: a descriptive study of the national database of the universal healthcare system in Japan. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13(6):7943-52 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33739304.

- 21.Galindo-Moreno P, et al. The impact of tooth loss on cognitive function. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26(4):3493-500 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34881401.

- 22.Stewart R, et al. Adverse oral health and cognitive decline: The health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):177-84 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23405916.

- 23.Dintica CS, et al. The relation of poor mastication with cognition and dementia risk: A population-based longitudinal study. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(9):8536-48 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32353829.

- 24.Kim MS, Han DH. Does reduced chewing ability efficiency influence cognitive function? Results of a 10-year national cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(25):e29270 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35758356.

- 25.Ko KA, et al. The Impact of Masticatory Function on Cognitive Impairment in Older Patients: A Population-Based Matched Case-Control Study. Yonsei Med J. 2022;63(8):783-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35914761.

- 26.Garre-Olmo J. [Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias]. Rev Neurol. 2018;66(11):377-86 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29790571.

- 27.Stephan BCM, et al. Secular Trends in Dementia Prevalence and Incidence Worldwide: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(2):653-80 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30347617.

- 28.Lopez OL, Kuller LH. Epidemiology of aging and associated cognitive disorders: Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;167:139-48 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31753130.

- 29.Ono Y, et al. Occlusion and brain function: mastication as a prevention of cognitive dysfunction. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(8):624-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20236235.

- 30.Kubo KY, et al. Masticatory function and cognitive function. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2010;87(3):135-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21174943.

- 31.Chen H, et al. Chewing Maintains Hippocampus-Dependent Cognitive Function. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12(6):502-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26078711.

- 32.Azuma K, et al. Association between Mastication, the Hippocampus, and the HPA Axis: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(8) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28771175.

- 33.Chuhuaicura P, et al. Mastication as a protective factor of the cognitive decline in adults: A qualitative systematic review. Int Dent J. 2019;69(5):334-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31140598.

- 34.Lopez-Chaichio L, et al. Oral health and healthy chewing for healthy cognitive ageing: A comprehensive narrative review. Gerodontology. 2021;38(2):126-35 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33179281.

- 35.Tada A, Miura H. Association between mastication and cognitive status: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;70:44-53 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28042986.

- 36.Ahmed SE, et al. Influence of Dental Prostheses on Cognitive Functioning in Elderly Population: A Systematic Review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2021;13(Suppl 1):S788-S94 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34447202.

- 37.Tonsekar PP, et al. Periodontal disease, tooth loss and dementia: Is there a link? A systematic review. Gerodontology. 2017;34(2):151-63 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28168759.

- 38.Nangle MR, Manchery N. Can chronic oral inflammation and masticatory dysfunction contribute to cognitive impairment? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2020;33(2):156-62 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31895157.

- 39.Nakamura T, et al. Oral dysfunctions and cognitive impairment/dementia. J Neurosci Res. 2021;99(2):518-28 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33164225.

- 40.Weijenberg RAF, et al. Mind your teeth-The relationship between mastication and cognition. Gerodontology. 2019;36(1):2-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30480331.

- 41.Asher S, et al. Periodontal health, cognitive decline, and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(9):2695-709 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36073186.

- 42.Lin CS. Revisiting the link between cognitive decline and masticatory dysfunction. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29304748.

- 43.Wu YT, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time – current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(6):327-39 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28497805.

- 44.National Psoriasis Foundation. Soriatane (Acitretin). https://www.psoriasis.org/soriatane-acitretin/.

- 45.National Psoriasis Foundation. Current Biologics on the Market. https://www.psoriasis.org/current-biologics-on-the-market/.

- 46.Dalmády S, Kemény L, Antal M, Gyulai R. Periodontitis: a newly identified comorbidity in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2020;16(1):101-8. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1700113.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Ira-Lamster-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2020/03/A-Mechanism-to-Explain-How-Periodontitis-Can-Affect-Pregnancy-Outcomes-2.jpg)