A Review of the Hall Technique: A minimally invasive option for treating carious primary molars

Dental caries is prevalent globally in children and adults.1Chen KJ, Gao SS, Duangthip D, Lo ECM, Chu CH. Prevalence of early childhood caries among 5-year-old children: A systematic review. J Investig Clin Dent 2019;10(1):e12376. doi:10.1111/jicd.12376.,2U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: A report of the Surgeon General, Executive summary. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. 2000. In the US, despite being a preventable disease, the prevalence of dental caries was recently found to be 21.4% among children ages 2–5 years and 50.5% among children between 6 and 11 years-of-age.3Fleming E, Afful J. Prevalence of Total and Untreated Dental Caries Among Youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief 2018;307. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db307.pdf. Furthermore, approximately 1 in 6 children suffer from untreated dental caries, with some groups disproportionately affected.3Fleming E, Afful J. Prevalence of Total and Untreated Dental Caries Among Youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief 2018;307. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db307.pdf. The Hall Technique (HT) was developed by Dr. Norna Hall in the 1980s as a minimally invasive method for treating primary molars with advanced stages of caries.4Innes NPT, Stirrups DR, Evans DJP, et al. A novel technique using preformed metal crowns for managing carious primary molars in general practice — A retrospective analysis. Br Dent J 2006; 451-454. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813466. It involves bonding a pre-formed metal crown (stainless steel crown; SSC) over the tooth, using a glass ionomer cement such that a marginal seal is obtained. In this article we will address carious primary molars, treatment options, results and considerations for HT.

Treatment options for carious primary molars

Options for primary molars with caries extending into dentin include the use of topical fluorides, conventional restorative care with complete caries removal (CRC), restorative care with selective caries removal (SE; leaving softened dentin close to the pulp), stepwise removal of caries in separate phases (SW), atraumatic restorative treatment, non-restorative cavity control with the lesion altered to enhance performance of local oral hygiene and prevention, silver diamine fluoride, SSC and HT.5Mijan MC, de Amorim RG, Mulder J, et al. Exfoliation rates of primary molars submitted to three treatment protocols after 3.5 years. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2015;43(3):232-239. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12147.,6Crystal YO, Janal MN, Yim S, Nelson T. Teaching and utilization of silver diamine fluoride and Hall-style crowns in US pediatric dentistry residency programs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(10):755-763. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.06.022.,7Ludwig KH, Fontana M, Vinson LA, et al. The success of stainless steel crowns placed with the Hall technique: a retrospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(12):1248-1253. doi: 10.14219/jada.2014.89.,8Schwendicke F, Walsh T, Lamont T, et al. Interventions for treating cavitated or dentine carious lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;Issue 7:CD013039. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013039.pub2. (Table 1) Specific treatment options for caries lesions depend on whether in the primary or permanent dentition, the tooth and surface, and the extent of the lesion. Patient management also plays a role in determining which treatment is most appropriate for a given patient.

| Table 1. Treatment options for lesions extending into dentin |

|---|

| Conventional restorative care with complete caries removal |

| Restorative care with selective caries removal |

| Restorative care with stepwise caries removal |

| Atraumatic restorative treatment |

| Non-restorative cavity control |

| Stainless steel crown |

| Hall Technique |

Topical Fluorides

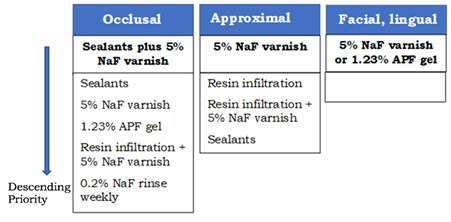

Topical fluorides are recommended for prevention, as well as for non-cavitated (incipient) and cavitated lesions, with the objective of arresting and reversing these.9Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT, et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review [published correction appears in J Am Dent Assoc. 2013 Dec;144(12):1335. Dosage error in article text]. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(11):1279-1291. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0057.,10Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions. A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149(10):837-849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002. For occlusal surfaces in primary molars, the use of sealants plus 5% NaF varnish applied every 3 to 6 months, or sealants alone is prioritized over other options (Figure 1). For approximal surfaces, 5% NaF varnish is prioritized, and for facial or lingual surfaces either 5% NaF varnish or 1.23% APF gel. Regardless of the option selected, lesions should be actively monitored and if necessary further treatment provided. For coronal cavitated lesions, 6-monthly application of 38% silver diamine fluoride (SDF) is prioritized over 5% sodium fluoride applied weekly for 3 weeks. (Figure 1)

HT and initial study results following its use

HT is a minimally invasive method for placement of SSC.4Innes NPT, Stirrups DR, Evans DJP, et al. A novel technique using preformed metal crowns for managing carious primary molars in general practice — A retrospective analysis. Br Dent J 2006; 451-454. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813466. After positioning it over the tooth, finger pressure or the child’s occlusal force is used to seat the SSC. HT is performed without local anesthesia (LA), caries removal, tooth preparation (reduction) or SSC preparation. Teeth with clinical and/or radiographic signs and symptoms of pulpal involvement, insufficient tooth structure for retention, or mobility (non-physiological) are not suitable for HT.11Evans D, Innes N. The Hall Technique. A minimal intervention, child centred approach to managing the carious primary molar. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/91/HallTechGuide_V4.pdf.

An initial retrospective study of HT procedures performed between March 1988 and January 1, 2001, was conducted.4Innes NPT, Stirrups DR, Evans DJP, et al. A novel technique using preformed metal crowns for managing carious primary molars in general practice — A retrospective analysis. Br Dent J 2006; 451-454. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813466. HT was provided to 259 children (mean age 69 months), with in total 978 primary molars treated. Success rates were based on the crown being present, or having been present until the primary tooth exfoliated, on the date at which children were lost to follow-up, or decementation/extraction occurred, or the study’s cut-off point. The survival probability at 3 and 5 years for HT was 73.4% and 67.6%, respectively, and 86% and 80.5%, respectively, for tooth survival. In total, 76% were deemed successful, with 42% of HT crowns present and a further 34% present until exfoliation. Decementation occurred in 13% of crowns and 11% were lost when the tooth was extracted (including for orthodontics). Study weaknesses include that radiographs were not routinely taken, and a retrospective study is weak compared to randomized controlled trials (RCT or other prospective studies).

Outcomes of Subsequent Studies on HT

Since the initial study, RCT, prospective studies, other retrospective studies and a systematic review have been conducted. In a Cochrane review published in July 2021, data from 27 RCT with 3,350 participants was used to compare treatments provided for non-cavitated and cavitated caries lesions extending into dentin.8Schwendicke F, Walsh T, Lamont T, et al. Interventions for treating cavitated or dentine carious lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;Issue 7:CD013039. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013039.pub2. Treatment success was typically evaluated 12 to 24 months post-treatment. For the primary dentition, it was concluded that HT or SE may be superior to CRC. For deep lesions, it was found that HT may have a lower failure rate than CRC, while results were equivocal in comparison to SE. A meta-analysis showed that failure was more likely for CRC compared to HT, SE or SW. However, a high risk of bias was found, and the majority of care was problem-free. It was concluded that future research was needed.8Schwendicke F, Walsh T, Lamont T, et al. Interventions for treating cavitated or dentine carious lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;Issue 7:CD013039. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013039.pub2.

In a split-mouth RCT with 132 children (ages 3 to 10 years), success rates were compared for carious primary molars (n=264) restored using conventional methods or HT.12Innes NPT, Evans DJP, Stirrups DR. Sealing Caries in Primary Molars: Randomized Control Trial, 5-year Results. J Dent Res. 2011;90(12):1405-1410. doi:10.1177/0022034511422064. The follow-up period ranged from 2 to 60 months, with annual radiographic and clinical exams, and 91 patients in each group had a 48-month minimum follow-up. For major failures (unrestorable/irreversible pulpitis/non-vital/abscess), the HT failure rate was 3% at 60 months while for conventional restorations it was 16.5%. Significantly more minor failures were seen for conventional restorations than HT crowns, with minor failures affecting 5% of HT and 42% of conventional restorations (minor failures included secondary caries, damage/loss of the restoration and reversible pulpitis). In a second RCT, care was provided by 13 dental therapists for 295 children ages 3 to 8 years. HT was compared to SE with conventional restorative methods (amalgam, composite, glass ionomer cement, or SSC).13Boyd DH, Thomson WM, Leon de la Barra S, et al. A Primary Care Randomized Controlled Trial of Hall and Conventional Restorative Techniques. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2021;6(2):205-212. doi: 10.1177/2380084420933154. At 2-years, 91% of subjects were available for evaluation. The highest success rates were found for HT and SCC with SE, at 85% and 86%, respectively.

In a randomized prospective study in children ages 5 to 8 years, more than 100 pre-formed crowns were placed in each group using HT or non-HT methods.14Elamin F, Abdelazeem N, Salah I, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing Hall vs conventional technique in placing preformed metal crowns from Sudan. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217740. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217740. A survival rate of more than 90% was found at 2 years for both the HT and non-HT treated teeth, with no statistically significant difference. Minor failures were reported for 2.7% and 5.8% of treatments, respectively, and major failures for 6.4% and 5.8%, respectively. In a non-randomized prospective study, treatment with a tooth-colored restorative material or HT was provided for 180 children ages 5 to 8 years for one carious primary molar.15Boyd DH, Page LF, Thomson WM. The Hall Technique and conventional restorative treatment in New Zealand children’s primary oral health care – clinical outcomes at two years. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2018;28(2):180-188. doi:10.1111/ipd.12324. At follow-up (mean 25 months, range 21-35 months), 147 children were available for evaluation. failure rates were 6% for HT and 32% for conventional direct restorations, and HT was more successful for deep caries lesions.

Several retrospective studies on HT have been conducted. In one study, 246 children (4 to 9 years-of-age) had attended two UK pediatric dentistry specialist hospital settings between 2006 and 2012 and received treatment with either CRC (n=425) or HT (n=408).16BaniHani A, Duggal M, Toumba J, Deery C. Outcomes of the conventional and biological treatment approaches for the management of caries in the primary dentition. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2018;28(1):12-22. doi:10.1111/ipd.12314. 95.3% and 95.8% of teeth remained asymptomatic, respectively. Follow-up had lasted up to 77 months for more than 800 advanced carious lesions. Final outcomes and success rates were similar regardless of treatment option or patient age. In a study with 65 children treated in a postgraduate pediatric dentistry setting (110 HT and 77 conventional SSC), At the 2-year endpoint of the 146 crowns available for evaluation, 97.6% of HT (n=84) and 93.5% of SSC (n=62) were successful.17Binladen H, Al Halabi M, Kowash M, et al. A 24-month retrospective study of preformed metal crowns: the Hall technique versus the conventional preparation method. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2021;22(1):67-75. doi:10.1007/s40368-020-00528-8. Four SSC failed due to abscesses and 2 HT due to perforation or abscess.

In a third retrospective study, HT was performed in children 2 to 10 years-of-age in a pediatric dentistry setting using standard HT or with proximal slicing prior to placement. 92.3% of procedures were clinically successful, 4 of 181 had minor failures and there were 10 major failures (abscess or irreversible pulpitis).18Midani R, Splieth CH, Mustafa Ali M, et al. Success rates of preformed metal crowns placed with the modified and standard hall technique in a paediatric dentistry setting. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019;29(5):550-556. doi:10.1111/ipd.12495. In a fourth retrospective study, success rates of 95% (110 of 117) and 97% (65 of 67) were found for SSC and HT, respectively.7Ludwig KH, Fontana M, Vinson LA, et al. The success of stainless steel crowns placed with the Hall technique: a retrospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(12):1248-1253. doi: 10.14219/jada.2014.89. Primary molars with clinical or radiographic evidence of pulpitis, necrosis or abscess were excluded, and follow-up lasted at least six months or until failure. Lastly, in a retrospective cohort study in 71 children ages 5 to 11 years, a 99% success rate was found for HT-treated teeth (n=113), with a mean follow-up of 17 months.19Sapountzis F, Mahony T, Villarosa AR, et al. A retrospective study of the Hall technique for the treatment of carious primary teeth in Sydney, Australia. First published: 08 April 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/cre2.421. (Table 2)

Table 2. Outcomes of studies

| Authors, year | Design | Subjects | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innes et al, 201112Innes NPT, Evans DJP, Stirrups DR. Sealing Caries in Primary Molars: Randomized Control Trial, 5-year Results. J Dent Res. 2011;90(12):1405-1410. doi:10.1177/0022034511422064. | Split-mouth RCT; HT vs CRC | 132 children; 264 teeth; (91 children minimum 48 months follow-up) | At 60 months, HT major and minor failure rates 3% and 5%; for conventional restorations, 16.5% and 42%, respectively. |

| Boyd et al, 202113Boyd DH, Thomson WM, Leon de la Barra S, et al. A Primary Care Randomized Controlled Trial of Hall and Conventional Restorative Techniques. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2021;6(2):205-212. doi: 10.1177/2380084420933154. | RCT; HT vs conventional restorative methods | 295 children; 91% of subjects available for 2-year evaluation | Highest success rates were for HT (85%) and SSC (86%). Lower success rates for direct restorations. |

| Elamin et al, 201914Elamin F, Abdelazeem N, Salah I, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing Hall vs conventional technique in placing preformed metal crowns from Sudan. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217740. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217740. | Randomized prospective; HT vs non-HT (SSC) | 100 pre-formed crowns placed | Survival rate >90% for HT and non-HT (SSC), no statistical difference. Minor failures 2.7% and 5.8% for HT and non-HT, respectively. Major failures for 6.4% and 5.8%, respectively. |

| Boyd et al, 201815Boyd DH, Page LF, Thomson WM. The Hall Technique and conventional restorative treatment in New Zealand children’s primary oral health care – clinical outcomes at two years. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2018;28(2):180-188. doi:10.1111/ipd.12324. | Non-randomized prospective; HT vs conventional tooth-colored restoration | 180 children, one carious primary molar treated by either method; 147 children available at follow-up | At follow-up (mean 25 months), success rates were 94% and 68% for HT and direct restorations, respectively. |

| Boyd et al, 20064Innes NPT, Stirrups DR, Evans DJP, et al. A novel technique using preformed metal crowns for managing carious primary molars in general practice — A retrospective analysis. Br Dent J 2006; 451-454. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813466. | Retrospective study on HT | 259 children (mean age 69 months); 978 teeth treated between March 1988 and Jan 1, 2001. | Survival probability at 3 and 5 years for HT crowns was 73.4% and 67.6%, respectively. In total, 76% were deemed successful. |

| Ludwig et al, 20147Ludwig KH, Fontana M, Vinson LA, et al. The success of stainless steel crowns placed with the Hall technique: a retrospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(12):1248-1253. doi: 10.14219/jada.2014.89. | Retrospective study on SSC and HT | 184 teeth; SSS-treated (n=117) and HT-treated (n=67) | Success rates 95% for SSC and 97% for HT. |

| BaniHani et al, 201816BaniHani A, Duggal M, Toumba J, Deery C. Outcomes of the conventional and biological treatment approaches for the management of caries in the primary dentition. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2018;28(1):12-22. doi:10.1111/ipd.12314. | Retrospective study on HT | 246 children treated with CRC (n=425 teeth) or HT (n=408). | 95.3% (CRC) and 95.8% (HT) remained asymptomatic. Follow-up up to 77 months. |

| Binladen et al, 202117Binladen H, Al Halabi M, Kowash M, et al. A 24-month retrospective study of preformed metal crowns: the Hall technique versus the conventional preparation method. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2021;22(1):67-75. doi:10.1007/s40368-020-00528-8. | Retrospective; HT vs conventional | 65 children; 110 HT and 77 SSC. 146 crowns available at 2-year follow-up. | Success rates were 97.6% for HT (n=84) and 93.5% for SSC (n=62). |

| Midani et al, 201918Midani R, Splieth CH, Mustafa Ali M, et al. Success rates of preformed metal crowns placed with the modified and standard hall technique in a paediatric dentistry setting. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019;29(5):550-556. doi:10.1111/ipd.12495. | Retrospective study; modified and standard HT | 181 procedures in children ages 2 to 10 years. | 92.3% clinically successful; 4 minor failures and10 major. |

| Sapountzis et al, 202119Sapountzis F, Mahony T, Villarosa AR, et al. A retrospective study of the Hall technique for the treatment of carious primary teeth in Sydney, Australia. First published: 08 April 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/cre2.421. | Retrospective study on HT | 71 children ages 5 to 11 years. | 99% success rate (n=113), mean follow-up 17 months. |

Concerns over outcomes

Concerns have been voiced over potential changes in occlusal vertical dimension, since HT leads to an initial increase in this parameter. In one study, a return to the pre-treatment occlusal vertical dimension was observed after 30 days, with the transient increase postulated to be caused by the HT-treated molar and its antagonist being intruded.20van der Zee V, van Amerongen WE. Short communication: Influence of preformed metal crowns (Hall technique) on the occlusal vertical dimension in the primary dentition. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2010;11(5):225-7. doi:10.1007/BF03262751. Additional research was recommended. In another study, the occlusal vertical dimension settled in three weeks and the occlusion within four weeks, with no difference in overbite measurements compared to baseline.21Joseph RM, Rao AP, Srikant N, et al. Evaluation of Changes in the Occlusion and Occlusal Vertical Dimension in Children Following the Placement of Preformed Metal Crowns Using the Hall Technique. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020;44(2):130-134.

doi:10.17796/1053-4625-44.2.12. There were no reports of temporomandibular joint pain following treatment. In a third study with a 1-year follow-up, 4 of 39 children were found to have temporomandibular joint problems, however these were not significantly different to pre-treatment.22Kaya MS, Kınay Taran P, Bakkal M. Temporomandibular dysfunction assessment in children treated with the Hall Technique: A pilot study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020;30(4):429-435. doi:10.1111/ipd.12620. In addition, it has been suggested that HT could result in early exfoliation of primary molars, however this is not supported by studies, and in a recent split-mouth study no evidence was found for early exfoliation.23Araujo MP, Uribe S, Robertson MD, et al. The Hall Technique and exfoliation of primary teeth: a retrospective cohort study. Br Dent J. 2020;228(3):213-217. doi:10.1038/s41415-020-1251-1.

Controversies

The debate over both partial caries removal and HT has been controversial. However, biologically, these treatment modalities are supported. Provided a good marginal seal exists (whether for a restoration or sealant), cariogenic bacteria present are isolated from fermentable carbohydrates and therefore cannot metabolize these to produce acid responsible for demineralization of tooth structure.24Holmgren C, Gaucher C, Decerle N, et al. Minimal intervention dentistry II: part 3. Management of non-cavitated (initial) occlusal caries lesions – non-invasive approaches through remineralisation and therapeutic sealants. Br Dent J. 2014;216:237-243. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.147. Numerous studies support this. Among them, a recently published three-arm RCT on caries management supports partial caries removal.25Maguire A, Clarkson JE, Douglas GVA, et al. Best-practice prevention alone or with conventional or biological caries management for 3- to 7-year-olds: the FiCTION three-arm RCT. Health Technol Assess 2020;24(1). https://doi.org/10.3310/hta24010 Further, in one review of 23 studies, outcomes for primary teeth were evaluated.26Thompson V, Craig RG, Curro FA, et al. Treatment of deep carious lesions by complete excavation or partial removal: A critical review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(6):705-712. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0252 For the 3 RCTs included, including a 10-year study, complete caries removal in deep carious lesions was found to be detrimental, risking pulpal exposure, while partial removal offered superior outcomes.

Other considerations

Non-invasive and minimally invasive treatments reduce the need for GA and sedation (and the risk of adverse events), as well as LA, can reduce anxiety, and may be useful in treating patients with learning disabilities.14Elamin F, Abdelazeem N, Salah I, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing Hall vs conventional technique in placing preformed metal crowns from Sudan. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217740. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217740.,27Arrow P, Forrest H. Atraumatic restorative treatments reduce the need for dental general anaesthesia: a non-inferiority randomized, controlled trial. Aust Dent J. 2020;65(2):158-167. doi:10.1111/adj.12749. ,28Lee H, Milgrom P, Huebner CE, et al. Ethics Rounds: Death After Pediatric Dental Anesthesia: An Avoidable Tragedy? Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20172370. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2370. ,29Robertson MD, Harris JC, Radford JR, Innes NPT. Clinical and patient-reported outcomes in children with learning disabilities treated using the Hall Technique: a cohort study. Br Dent J. 2020;228(2):93-97. doi:10.1038/s41415-019-1166-x. Procedure time is also reduced with HT compared to conventional treatment, and in several settings has been found to be more cost-effective than standard treatment (with/without GA), based on direct and cumulative costs.14Elamin F, Abdelazeem N, Salah I, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing Hall vs conventional technique in placing preformed metal crowns from Sudan. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217740. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217740.,30Schwendicke F, Krois J, Robertson M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the Hall Technique in a Randomized Trial. J Dent Res. 2019;98(1):61-67. doi:10.1177/0022034518799742. ,31Tonmukayakul U, Forrest H, Arrow P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of atraumatic restorative treatment to manage early childhood caries: microsimulation modelling. Aust Dent J. 2021;May 24. doi:10.1111/adj.12857.,32Ebrahimi M, Shirazi AS, Afshari E. Success and Behavior During Atraumatic Restorative Treatment, the Hall Technique, and the Stainless Steel Crown Technique for Primary Molar Teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2020;42(3):187-192. In one RCT with 169 children, parents rated their child’s comfort level similarly for CRC, non-restorative care and HT.33Santamaria RM, Innes NP, Machiulskiene V, et al. Acceptability of different caries management methods for primary molars in a RCT. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2015;25(1):9-17. doi:10.1111/ipd.12097. Pain was self-rated as low or very low by 72%, 81% and 88% of children receiving, respectively, CR, HT, and NRT. Good patient and parental acceptance of HT has been found across several studies.25Maguire A, Clarkson JE, Douglas GVA, et al. Best-practice prevention alone or with conventional or biological caries management for 3- to 7-year-olds: the FiCTION three-arm RCT. Health Technol Assess 2020;24(1). https://doi.org/10.3310/hta24010,34Bell S, Morgan A, Marshman Z, Rodd H. Child and parental acceptance of preformed metal crowns. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2010;11:218-224.,35Innes NPT, Evans DJP, Stirrups DR. Sealing Caries in Primary Molars: Randomized Control Trial, 5-year Results. J Dent Res. 2011;90(12):1405-10. doi:10.1177/0022034511422064.,36Jackson G. Placement of preformed metal crowns on carious primary molars by dental hygiene/therapy vocational trainees in Scotland: A service evaluation assessing patient and parent satisfaction. Prim Dent J. 2015;4(4):46-51. doi:10.1308/205016815816682218. ,37Altoukhi DH, El-Housseiny AA. Hall Technique for Carious Primary Molars: A Review of the Literature. Dent J (Basel). 2020;8(1):11. doi: 10.3390/dj8010011. HT is also one of the methods to minimize aerosol generation during treatment, one approach to reducing risk during COVID-19.38Eden E, Frencken J, Gao S, et al. Managing dental caries against the backdrop of COVID-19: approaches to reduce aerosol generation. Br Dent J. 2020;229:411-416. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2153-y

Teaching in Pediatric Dentistry Programs

In a recent survey of US pediatric residency program directors, teaching and utilization of HT and silver diamine fluoride were assessed for 2015 and 2021.6Crystal YO, Janal MN, Yim S, Nelson T. Teaching and utilization of silver diamine fluoride and Hall-style crowns in US pediatric dentistry residency programs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(10):755-763. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.06.022. All respondents (89% response rate) indicated that they now used SDF for caries arrestment. HT didactic training is provided in 90% of programs with directors responding and to varying degrees in the clinic by 69.5%. Barriers to conventional treatment that increased use of HT and SDF included lengthy wait lists for operating rooms and sedation.

Conclusions

Treatment considerations for carious primary molars include the extent of the caries lesion, presence/absence of pulpal involvement, ease of treatment, patient cooperation, parental and patient acceptance, invasiveness, the need for GA/LA. HT is a minimally invasive method that has been controversial, and further research has been recommended. In the meantime, several studies in different settings and geographies have demonstrated good success rates with HT while providing minimally invasive care. HT success rates at least equal to or better than other restorative options have been found in studies comparing outcomes. Additionally, HT is now being taught in dental education settings. In conclusion, with appropriate case selection, HT provides an added minimally invasive treatment option for carious primary molars.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: A report of the Surgeon General, Executive summary. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. 2000.

- 2.Chen KJ, Gao SS, Duangthip D, Lo ECM, Chu CH. Prevalence of early childhood caries among 5-year-old children: A systematic review. J Investig Clin Dent 2019;10(1):e12376. doi:10.1111/jicd.12376

- 3.Fleming E, Afful J. Prevalence of Total and Untreated Dental Caries Among Youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief 2018;307. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db307.pdf.

- 4.Dye B, Thornton-Evans G, Li X, Iafolla T. Dental caries and tooth loss in adults in the United States, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;197.

- 5.Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD, Ekstrand K, Weintraub JA, Ramos-Gomez F, et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;25(3):17030.

- 6.World Health Organization. Risk factors. Available at: https://www.who.int/topics/risk_factors/en/

- 7.Tagliaferro E, Pardi E, Ambrosano V, Meneghim G, Pereira, MAC. An overview of caries risk assessment in 0-18 year-olds over the last ten years (1997-2007). Braz J Oral Sci 2008;7(27):7.

- 8.Bibby BG, Krobicka A. An in vitro method for making repeated pH measurements on human dental plaque. J Dent Res 1984;63:906-9.

- 9.American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age 0-6). Available at: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/FIles/topics_caries_under6.pdf.

- 10.American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age >6). Available at: http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/Files/topic_caries_over6.ashx.

- 11.AAPD. Caries-risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Latest revision, 2019. Available at: https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf

- 12.AAPD. Best Practices. Perinatal and Infant Oral Health Care. 2016.. Available at: https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_perinataloralhealthcare.pdf.

- 13.Dasanayake AP, Warnakulasuriya S, Harris CK, Cooper DJ, Peters TJ, Gelbier S. Tooth decay in alcohol abusers compared to alcohol and drug abusers. Int J Dent 2010;2010:786503.

- 14.Boersma JG, van der Veen MH, Lagerweij MD, Bokhout B, Prahl-Andersen B. Caries prevalence measured with QLF after treatment with fixed orthodontic appliances: influencing factors. Caries Res 2005;39(1):41-7.

- 15.Opal S, Garg S, Jain J, Walia I. Genetic factors affecting dental caries risk. Aust Dent J 2015;60:2-11.

- 16.Gomez A, Espinoza JL, Harkins DM, Leong P, Saffery R, Bockmann M et al. Host genetic control of the oral microbiome in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2017;22:269-78 e263.

- 17.Featherstone JDB, Alston P, Chaffee BW, Rechmann P. Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA)*: An Update for Use in Clinical Practice for Patients Aged Through Adult. In: CAMBRA® Caries Management by Risk Assessment A Comprehensive Caries Management Guide for Dental Professionals. (2019) Available at: https://www.cdafoundation.org/Portals/0/pdfs/cambra_handbook.pdf.

- 18.Cagetti MG, Bontà G, Cocco F, Lingstrom P, Strohmenger L, Campus G. Are standardized caries risk assessment models effective in assessing actual caries status and future caries increment? A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2018;18(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0585-4.

- 19.Malmö University. Cariogram – Download. Available at: https://www.mah.se/fakulteter-och-omraden/Odontologiska-fakulteten/Avdelning-och-kansli/Cariologi/Cariogram/.

- 20.Petsi G , Gizani S, Twetman S, Kavvadia K. Cariogram caries risk profiles in adolescent orthodontic patients with and without some salivary variables. Angle Orthod 2014;84(5):891-5. doi:10.2319/080113-573.1.

- 21.Martin J, Mills S, Foley ME. Innovative models of dental care delivery and coverage. Patient-centric dental benefits based on digital oral health risk assessment. Dent Clin N Am 2018;62:319-25.

- 22.Chapple L, Yonel Z. Oral Health Risk Assessment. Dent Update 2018;45:841-7.

- 23.American Dental Association. Electronic oral health risk assessment tools. SCDI White Paper No. 1074, 2013. Available at: http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/Files/ADAWhitePaperNo1074.pdf?la=en.

- 24.Twetman S, Banerjee A. (2020) Caries Risk Assessment. In: Chapple I, Papapanou P. (eds) Risk Assessment in Oral Health. Springer, Cham.

- 25.Rechmann P, Chaffee BW, Rechmann BMT, Featherstone JDB. Caries Management by Risk Assessment: Results From a Practice-Based Research Network Study. J Calif Dent Assoc 2019;47(1):15-24.

- 26.Mertz E, Wides C, White J. Clinician attitudes, skills, motivations and experience following the implementation of clinical decision support tools in a large dental practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2017;17(1):1-12.

- 27.Dou L, Luo J, Fu X, Tang Y, Gao J, Yang D. The validity of caries risk assessment in young adults with past caries experience using a screening Cariogram model without saliva tests. Int Dent J 2018;68(4):221-6. doi: 10.1111/idj.12378

- 28.Thyvalikakath T, Song M, Schleyer T. Perceptions and attitudes toward performing risk assessment for periodontal disease: a focus group exploration. BMC Oral Health 2018;18(1):90.

- 29.Riley JL 3rd, Gordan VV, Ajmo CT, Bockman H, Jackson MB, Gilbert GH. Dentists’ use of caries risk assessment and individualized caries prevention for their adult patients: findings from The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2011;39(6):564-73.

- 30.Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo T, Frantsve-Hawley J, Meyer DM, Beltrán-Aguilar ED et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91. doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0057

- 31.American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Fluoride toothpaste use for young children. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;145(2):190-1. doi.org/10.14219/jada.2013.47

- 32.Wright JT, Crall JJ, Fontana M, Gillette EJ, Nový BB, Dhar V et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the use of pit-and-fissure sealants. A report of the American Dental Association and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 2016;147(8):672-82.E12. doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2016.06.001

- 33.Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB, Fontana M, Guzmán-Armstrong S, Nascimento MM et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions. A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(10):P837-49.E10. doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002

- 34.Baskaradoss JK. Relationship between oral health literacy and oral health status. BMC Oral Health 2018;18:172. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0640-1.

- 35.Collins FM. Oral health literacy. Available at: https://www.colgateoralhealthnetwork.com/article/oral-health-literacy/

- 36.Alian AY, McNally ME, Fure S, Birkhed D. Assessment of Caries Risk in Elderly Patients Using the Cariogram Model. J Can Dent Assoc 2006;72(5):459–63.

- 37.Edwards AGK, Hood, K, Matthews EJ et al. The effectiveness of one to one risk communication interventions in health care: a systematic review. Med Decis Making 2000;20:290-7.

- 38.Eden E, Frencken J, Gao S, et al. Managing dental caries against the backdrop of COVID-19: approaches to reduce aerosol generation. Br Dent J. 2020;229:411-416. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2153-y

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Fiona-Collins-thumbnail-1-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2021/12/hall-technique-article-2.jpg)