An Update on Caries Prevention and Management for Pediatric Patients

Dental caries is a multifactorial disease with an estimated global prevalence of 60% to 90% among schoolchildren.1World Health Organization. Global oral health status report. Towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. (2022.) https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484. This article will address dental caries in the US pediatric population and then focus on caries risk, recommendations, guidelines and best practices published by the American Association of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) and American Dental Association (ADA).

Prevalence of dental caries in pediatric patients

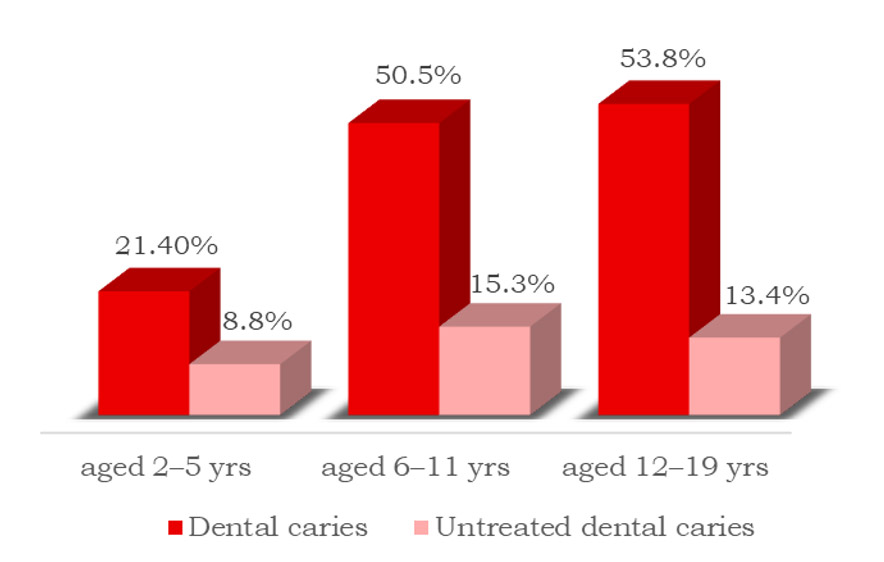

The prevalence of treated and untreated dental caries among individuals aged 2–5 years, 6–11 and 12–19 years in the US is estimated at 21.4%, 50.5% and 53.8%, respectively, with an overall prevalence of 45.8%.2Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence of Total and Untreated Dental Caries Among Youth: United States, 2015–2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db307.htm. For untreated dental caries, the estimated prevalence is 8.8%, 15.3% and 13.4%, respectively. (Figures 1,2) However, dental caries is preventable and can be arrested and reversed with suitable interventions.

Figure 2. Patient with untreated caries lesions in the primary dentition

Source: iStock.com/Anton Shulgin

In the primary dentition, the prevalence of untreated dental caries is estimated at 10% and 16% for children aged 2–5 and 6–8 years, respectively.3Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health. Dental Caries in Primary Teeth. Oral Health Surveillance Report, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/OHSR-2019-dental-caries-primary-teeth.html. (Figure 2) Furthermore, early childhood caries (ECC) is recognized as a significant public health problem, and is defined as ‘the presence of one or more decayed (noncavitated or cavitated lesions), missing (due to caries), or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a child 71 months of age or younger.’4American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Early Childhood Caries (ECC): Classifications, Consequences, and Preventive Strategies. 2016. https://www.aapd.org/media/policies_guidelines/p_eccclassifications.pdf. In a child under three years-of-age, any sign of dental caries on smooth surfaces is categorized as severe early childhood caries (S-ECC). Children ages three through five also experience S-ECC, with the definition changing by age group – in the case of a five-year-old child, the existence of six or more decayed, missing or filled teeth, or on filled smooth surfaces in primary maxillary anterior teeth.

Caries risk

Following exposure to acid of bacterial origin, demineralization of tooth structure with loss of calcium, phosphate and carbonate ions begins when the pH drops below the critical level (for enamel, this is pH <5.5). As such, the presence of cariogenic bacteria and fermentable carbohydrates are prerequisites for dental caries.5Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;25(3):17030. Other factors include destructive factors that increase risk and protective factors that reduce risk. Disease indicators are not risk factors, they are indicative of risk (for example, white spot lesions).6Ricketts D, Chadwick G, Hall A. Management of dental caries. In: Advanced operative dentistry: A practical approach. (2011) Ch 1, p1-15. Rickets D, Bartlett D (eds). Elsevier Ltd.

Caries risk assessment (CRA)

The AAPD recommends in its updated CRA best practices for children and adolescents (2022) that CRA begin at the age one visit.7American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Caries-risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Latest revision, 2019. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf. Risk assessment forms available from the AAPD address ages 0–5 years and age 6 years and above, while the ADA forms address ages 0–6 years and over age 6.7American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Caries-risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Latest revision, 2019. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf.,8American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age 0-6). https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/oral-health-topics/ada_caries_risk_assessment.pdf?rev=35c455eadb104d02aee629ed58513d0b&hash=B0DCCECEDB4349E9D67F75D77CA720AD.,9American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age >6). https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/oral-health-topics/topic_caries_over6.pdf?rev=c5b718b48dd644958d9482c96ab8e874&hash=C4B61882C2A4AB23DEE58D1D5A7417D3. These forms provide a list of protective and destructive risk factors, and risk indicators. The patient’s caries risk level (low, moderate or high) is based on the overall results. Other CRA tools include CAMBRA, Cariogram, OHIS and DEPPA.10Featherstone JDB, Alston P, Chaffee BW, Rechmann P. Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA)*: An Update for Use in Clinical Practice for Patients Aged Through Adult. In: CAMBRA® Caries Management by Risk Assessment A Comprehensive Caries Management Guide for Dental Professionals. (2019) https://www.cdafoundation.org/Portals/0/pdfs/cambra_handbook.pdf.,11Malmö University. Cariogram – Download. https://www.mah.se/fakulteter-och-omraden/Odontologiska-fakulteten/Avdelning-och-kansli/Cariologi/Cariogram/.,12Chapple L, Yonel Z. Oral Health Risk Assessment. Dent Update 2018;45:841-7. Based on a recent publication, while there is insufficient evidence to favor a specific tool, the predictive accuracy of CRA can be >80% for pre-school and school-age children.13Twetman S, Banerjee A. Caries Risk Assessment (2020). In: Chapple I, Papapanou P. (eds) Risk Assessment in Oral Health. Springer, Cham. Formal CRA tools offer standardization, and digital tools offer easy archiving and easier comparison of risk and outcomes over time. CRA should be performed periodically as a patient’s risk level can change.

Knowing a given patient’s caries risk level and the risk factors involved is invaluable for patient education, and helps clinicians plan, recommend and implement appropriate tailored interventions. In addition to varying prevention recommendations, the AAPD recommends recalls and radiographs at different frequencies based on risk level.14U.S. Public Health Service Recommendation for Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Water for the Prevention of Dental Caries. Public Health Rep 2015;130(4):318-31. (Table 1)

| Table 1. Frequency of recalls and radiographs for all pediatric patients | ||

|---|---|---|

| Recalls | Radiographs | |

| Low risk | Every 6 to 12 months | Every 12 to 24 months |

| Moderate risk | Every 6 months | Every 6 to 12 months |

| High risk | Every 3 months | Every 6 months |

Caries prevention in pediatric patients

Recommendations for the prevention and management of dental caries are provided by the AAPD and ADA. General recommendations include dietary counselling (with parents/guardians and/or patients) and drinking optimally fluoridated water (0.7 ppm fluoride) as a proven method of reducing caries.14U.S. Public Health Service Recommendation for Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Water for the Prevention of Dental Caries. Public Health Rep 2015;130(4):318-31.

Preventive measures

Preventive measures for pediatric patients include fluorides and pit-and-fissure sealants. Other agents, including xylitol, that can be used adjunctively in helping to prevent dental caries are outside the scope of this article.

Topical Fluorides

Fluoride toothpaste: Twice-daily brushing with fluoride toothpaste is recommended.15American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride therapy, revised 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_fluoridetherapy.pdf,16American Dental Association. Fluoride: Topical and Systemic Supplements. https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral%20health-topics/fluoride-topical-and-systemic-supplements. Children under age 3 years-of-age should brush with a smear of fluoride toothpaste (amount of a grain of rice), beginning after the first primary tooth erupts, and a pea-sized amount is recommended for children 3 to 6 years-of-age.17Wright JT, Hanson N, Ristic H et al. Fluoride toothpaste efficacy and safety in children younger than 6 years. J Am Dent Assoc 2014;145(2):182-9. Children should be supervised once old enough to brush their own teeth, and spit after brushing to reduce potential ingestion of fluoride and the risk of dental fluorosis (DF).

In-office topical fluoride: Only 5% sodium fluoride varnish (NaFV) is recommended for children under age 6.15American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride therapy, revised 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_fluoridetherapy.pdf,18Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo T et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: Executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4581720/. The ADA recommends application at least every 3 to 6 months, based on risk level. The AAPD also recommends at least twice per year, and an example of a care pathway for under age 3 suggests every 3 months for moderate and high-risk patients.7American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Caries-risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Latest revision, 2019. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf.,15American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride therapy, revised 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_fluoridetherapy.pdf In addition, only unit doses of NaFV are recommended for children under age six.15American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride therapy, revised 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_fluoridetherapy.pdf For patients aged 6 and over, options include NaFV and a 4-minute application of 1.23% APF gel. (Table 2)

| Table 2. Topical fluorides for caries prevention in pediatric patients | |

|---|---|

| Patients at low caries risk | Twice-daily use of fluoride toothpaste may be sufficient |

| Under age 6 at increased risk for caries |

In-office: NaFV at least every 3 to 6 months Home use: Twice-daily use of regular fluoride toothpaste at an age-appropriate dose |

| Age 6 + at increased risk for caries |

In-office: NaFV or 4-minute application of 1.23% APF Gel at least every 3 to 6 months Home use: Twice-daily use of 5,000 ppm fluoride paste/gel (higher risk) Rinsing with 0.02% fluoride ion rinse (daily) or 0.09% fluoride ion rinse (weekly) |

Prescription-level fluoride toothpaste/gel: 1.1% sodium fluoride (5000 ppm fluoride) is recommended and supported by the ADA and AAPD for patients 6 years-of-age and over at higher risk for caries.15American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride therapy, revised 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_fluoridetherapy.pdf,18Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo T et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: Executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4581720/. Prescription-level fluoride toothpastes/gels are generally not recommended for younger children due to the risk of ingestion. However, based on clinical judgment, the clinician may determine that the benefit outweighs the risk for a given patient at high risk.18Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo T et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: Executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4581720/.

Rinses: Lastly, the use of 0.02% fluoride ion mouth rinse (0.05% NaF rinse; daily) to 0.09% fluoride ion mouth rinse (0.2% sodium fluoride rinse; weekly) are options for high-risk patients aged six and over years of age. These should not be used by younger children due to the risk of swallowing. (Table 2)

Mechanisms of Action

Topical fluoride exposure results in the presence of free fluoride ions in plaque, saliva and on oral mucosa.19Cruz RA, Rolla G. A scanning electron microscope investigation of calcium fluoride-like material deposited during topical fluoride exposure on sound human enamel in vitro. Braz J Med Biol Res 1994;27(10):2371-7. At higher concentrations, calcium fluoride-like globules form and function as fluoride reservoirs on teeth – releasing fluoride during an acid attack.20Arends J, Christoffersen J. Nature and role of loosely bound fluoride in dental caries. J Dent Res 1990;69(Spec Iss):601-5.,21Saxegaard E, Lagerlöf F, Rølla G. Dissolution of calcium fluoride in human saliva. Acta Odontol Scand 1988;46(6):355-9.,22Tenuta LM, Cerezetti RV, Del Bel Cury AA et al. Fluoride release from CaF2 and enamel demineralization. J Dent Res 2008;87(11):1032-6. The concentration, duration and frequency of application all contribute to the amount of fluoride present. Topical fluoride mechanisms of action include: 1) Inhibiting demineralization and promoting remineralization. Under favorable conditions, supersaturation of calcium and phosphate in saliva helps to prevent demineralization and favors rapid remineralization with calcium and phosphate. Fluoride adsorbs to the tooth surface, then attracting calcium ions which in turn attract phosphate ions and accelerate remineralization. Fluoride uptake also occurs; 2) Interfering with bacterial metabolic activity and acid production;23Hamilton IR. Biochemical effects of fluoride on oral bacteria. J Dent Res 1990;69(special issue):660-7. and 3) Causing bacterial cell death (if a high concentration of fluoride is applied at the tooth surface).

Systemic Fluoride – Supplements

The effect of systemic fluorides is mainly topical – during chewing/dissolution of the supplement, and after ingestion by its presence in saliva and gingival crevicular fluid. Fluoride incorporated into tooth structure during tooth development plays a minor role in caries prevention. Caution is advised before considering fluoride supplements as excessive fluoride ingestion by younger children can result in DF.15American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride therapy, revised 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_fluoridetherapy.pdf (Figure 3)

DF can develop only when excess fluoride is ingested prior to pre-eruptive enamel maturation.24Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fluoride Recommendations Work Group. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001;50(RR-14):1-42. The risk and severity of DF depend on the total amount of fluoride ingested, the timeline involved and the child’s age. The crowns of first permanent molars are fully formed by around age 3, and the permanent central and lateral incisors by 4 to 5 years-of-age.25American Association of Pediatric Dentists. Dental growth and development. Reference Manual V30/N6/18/19. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/r_dentalgrowth.pdf. By around age 8, all permanent teeth are fully formed, with the exception of third molars. (Table 3)

| Table 3. Age by which the crowns of permanent teeth are fully formed | |

|---|---|

| First permanent molars | By age 3 years |

| Central and lateral incisors | By age 4 to 5 years |

| First premolars | By age 5 to 6 years |

| Canines, second premolars | By age 6 to 7 years |

| Second molars | By age 7 to 8 years |

All sources that contribute to total dietary fluoride intake must first be determined if fluoride supplements are a consideration. Sources include intentionally or naturally fluoridated water, juices, sodas, fish, foods prepared/processed in fluoridated water, concentrated or powdered infant formula reconstituted with fluoridated water, certain medications and repeated unintentional ingestion of home use topical fluorides.26U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Federal Panel on Community Water Fluoridation. U.S. Public Health Service Recommendation for Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Water for the Prevention of Dental Caries. Public Health Reports July–August 2015;130:318-31.,27Levy SM, Broffitt B, Marshall TA et al. Associations between fluorosis of permanent incisors and fluoride intake from infant formula, other dietary sources and dentifrice during early childhood. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141:1190–201.,28Heilman JR, Kiritsy MC, Levy SM, Wefel JS. Assessing fluoride levels of carbonated soft drinks. J Am Dent Assoc 1999;130(11):1593-9.,29Berg J, Gerweck C, Hujoel PP et al. Evidence-based clinical recommendations regarding fluoride intake from reconstituted infant formula and enamel fluorosis. J Am Dent Assoc 2011;142(1):79-87. Should supplements be prescribed, the recommended dosing is shown in Table 4. Fluoride supplements should never be prescribed unless the water supply is fluoride-deficient (<0.6 ppm fluoride).15American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride therapy, revised 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_fluoridetherapy.pdf

Table 4. Dosing for fluoride supplements by age, water supply’s ppm fluoride

| Fluoride concentration | Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up to 6 months | 6 months to 3 yrs. | 3 to 6 yrs. | 6 to 16 yrs. | |

| <0.3 ppm | None | 0.25 mg/day | 0.50 mg/day | 1.0 mg/day |

| 0.3 to 0.6 ppm | None | None | 0.25 mg/day | 0.50 mg/day |

| >0.6 ppm | None | None | None | None |

Pit-and-fissure sealants

Figure 4. Partially erupted first permanent molar and an operculum compromising isolation in a patient at risk for caries.

The AAPD and ADA published updated information on pit-and-fissure sealants in 2016, based on the results of a systematic review by a panel convened by the ADA Council on Scientific Affairs and the AAPD.30American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Oral Health Policies & Recommendations (The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry). Use of Pit-and-Fissure Sealants (2016). https://www.aapd.org/research/oral-health-policies–recommendations/pit_and_fissure_sealants/.,31American Dental Association. Pit-and-Fissure Sealants Clinical Practice Guideline (2016). https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/evidence-based-dental-research/sealants-clinical-practice-guideline. It was concluded that sealants are effective in preventing occlusal caries in the primary and permanent dentition in children and adolescents, and the AAPD recommended that clinicians should focus more on greater use of sealants.30American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Oral Health Policies & Recommendations (The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry). Use of Pit-and-Fissure Sealants (2016). https://www.aapd.org/research/oral-health-policies–recommendations/pit_and_fissure_sealants/. The ADA guidelines recommend sealants for children and adolescents on sound occlusal surfaces in primary and permanent molars.31American Dental Association. Pit-and-Fissure Sealants Clinical Practice Guideline (2016). https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/evidence-based-dental-research/sealants-clinical-practice-guideline. (Figure 3) Of note, 80 to 90% of caries in permanent posterior teeth and 44% in primary teeth occurs in pits and fissures.32Ferreira Zandona AG, Ritter AV, Eidson RS. Dental caries: Etiology, caries risk assessment, and management. Ch2, p43. In: Ritter AV, Boushell LW, Walter R. Sturdevant’s art & science of operative dentistry-e-book. 7th Ed. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2017. Based on the available evidence, as noted in the ADA guidelines, it was not possible to determine the superiority of a sealant material compared to others (options include glass ionomer sealants, resin-modified glass ionomer sealants, resin-based composite sealants and compomers).31American Dental Association. Pit-and-Fissure Sealants Clinical Practice Guideline (2016). https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/evidence-based-dental-research/sealants-clinical-practice-guideline. Furthermore, it was suggested that clinicians consider patient factors and the clinical situation – for example, in situations where isolation is difficult (not possible to obtain a dry field) such as when a tooth is not fully erupted (Figure 4) that a hydrophilic material be used. Examples include GI and RMGI, which are moisture tolerant.

Management of existing caries lesions in pediatric patients

Caries lesions consist of non-cavitated lesions (including white spot lesions) and cavitated lesions – those that have progressed to advanced lesions with loss of integrity of the tooth.32Ferreira Zandona AG, Ritter AV, Eidson RS. Dental caries: Etiology, caries risk assessment, and management. Ch2, p43. In: Ritter AV, Boushell LW, Walter R. Sturdevant’s art & science of operative dentistry-e-book. 7th Ed. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2017. Many lesions do not progress from non-cavitated to cavitated and may either be arrested or reversed. During recalls, patients should be examined for caries lesions, their stage/progression and activity. Interventions should be provided as needed, and early caries lesions managed conservatively and monitored. Nonrestorative options avoid/minimize loss of tooth structure and can remove a cycle of expanded restorative care from the equation. They are also the least resource intensive, and more comfortable and attractive to patients than invasive options.

Non-cavitated lesions

The AAPD and ADA provide recommendations for the nonrestorative treatment of non-cavitated lesions based on the tooth surface. This includes topical fluorides, sealants, resin infiltration and other interventions.

Prioritized guidelines and systematic reviews

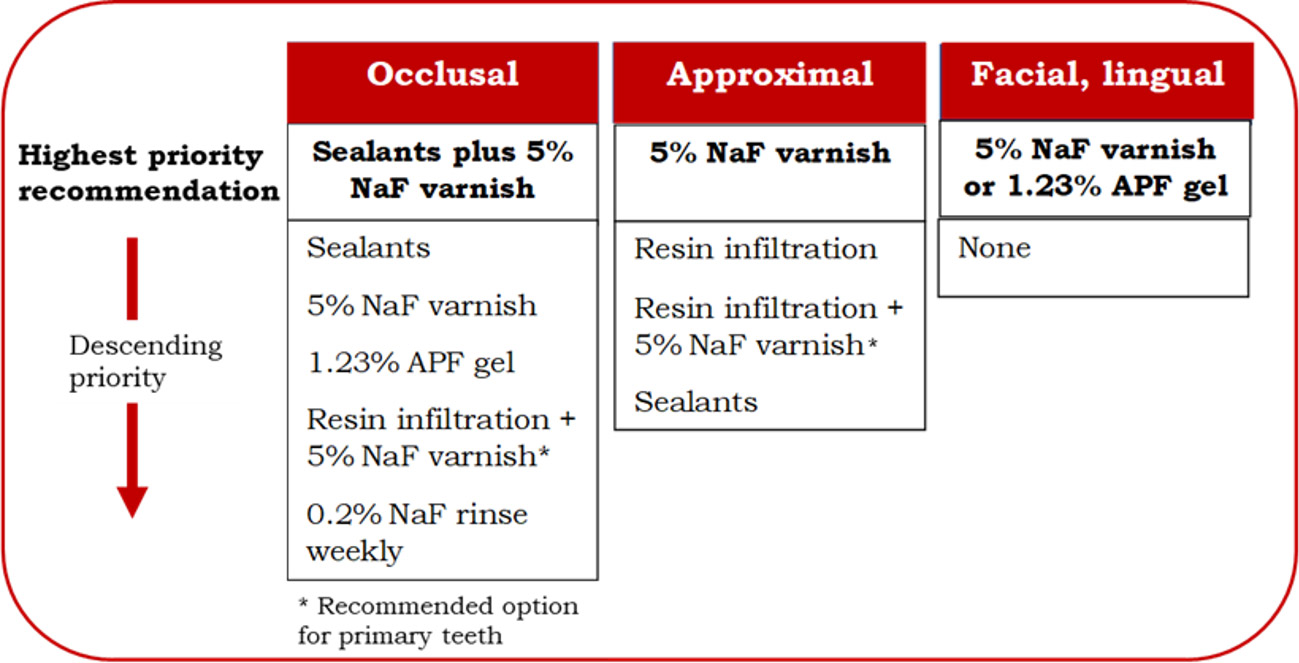

Figure 5. Prioritized interventions for non-cavitated coronal lesions33Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(10):837-49. e19. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002.

In 2018, the ADA published guidelines on the nonrestorative treatment of caries lesions.33Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(10):837-49. e19. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002. These were based on a systematic review of forty-four randomized controlled trials (RCT) already conducted but published in 2019.33Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(10):837-49. e19. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002.,34Urquhart O, Tampi MP, Pilcher L et al. Nonrestorative Treatments for Caries: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J Dent Res 2019;98(1):14-26. doi: 10.1177/0022034518800014. The ADA guidelines prioritized treatments for non-cavitated caries lesions by surface with the following highest priorities:

Occlusal – Application of sealants plus application every 3 to 6 months of NaFV is the highest priority recommendation.

Approximal – Application of NaFV.

Facial and lingual – application of NaFV or 1.23% APF gel. (Figure 5)

Several systematic reviews have confirmed the efficacy of sealants in arresting pit-and-fissure occlusal non-cavitated caries lesions in the primary and permanent molars in children and adolescents compared with NaFV or nonuse of sealants, and can minimize progression.30American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Oral Health Policies & Recommendations (The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry). Use of Pit-and-Fissure Sealants (2016). https://www.aapd.org/research/oral-health-policies–recommendations/pit_and_fissure_sealants/.,34Urquhart O, Tampi MP, Pilcher L et al. Nonrestorative Treatments for Caries: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J Dent Res 2019;98(1):14-26. doi: 10.1177/0022034518800014.,35Cabalén MB, Molina GF, Bono A, Burrow MF. Nonrestorative Caries Treatment: A Systematic Review Update. Int Dent J 2022;72(6):746-64. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2022.06.022. Sealant application plus NaFV has been found to provide a more than three-fold likelihood of caries arrestment/reversal compared to no treatment.34Urquhart O, Tampi MP, Pilcher L et al. Nonrestorative Treatments for Caries: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J Dent Res 2019;98(1):14-26. doi: 10.1177/0022034518800014. Additionally, in the most recent systematic review (2022), similar efficacy was found for resin-based and glass ionomer sealants.35Cabalén MB, Molina GF, Bono A, Burrow MF. Nonrestorative Caries Treatment: A Systematic Review Update. Int Dent J 2022;72(6):746-64. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2022.06.022.

In 2016, the AAPD included resin infiltration in its ‘Guideline on Restorative Dentistry’.36American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Restorative Dentistry, 2016. https://www.aapd.org/assets/1/7/G_Restorative1.PDF. The evidence was supportive of resin infiltration for small, non-cavitated approximal caries lesions in permanent teeth.36American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Restorative Dentistry, 2016. https://www.aapd.org/assets/1/7/G_Restorative1.PDF. During resin infiltration, the resin enters incipient enamel pores through capillary action and fills them, at the same time creating a barrier.37Faghihian R, Shirani M, Tarrahi MJ, Zakizade M. Efficacy of the Resin Infiltration Technique in Preventing Initial Caries Progression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr Dent 2019;41(2):88-94. ,38American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Minimally Invasive Dentistry, Adopted 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/p_minimallyinvasivedentistry.pdf.,39Paris S, Hopfenmuller W, Meyer-Lueckel H. Resin infiltration of caries lesions: An efficacy randomized trial. J Dent Res 2010;89(8):823-6. Resin infiltration is effective against proximal lesions in dentin in both the primary and permanent detention, based on 10 randomized controlled trials (RCT) in the 2022 systematic review, with caries arrestment rates ranging from 37.5% to 64.1% at 12 months and 48% at 30 months.35Cabalén MB, Molina GF, Bono A, Burrow MF. Nonrestorative Caries Treatment: A Systematic Review Update. Int Dent J 2022;72(6):746-64. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2022.06.022. The ADA guidelines include resin infiltration for approximal lesions, and resin infiltration plus NaFV every six months as an option for the primary dentition.33Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(10):837-49. e19. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002. Ranking of prioritization is based on data on efficacy, resource efficiency, patient values and preferences, and feasibility.

Managing cavitated lesions in pediatric patients

For the nonrestorative management of cavitated coronal lesions in primary and permanent teeth, 6-monthly application of SDF is prioritized over NaFV weekly application for 3 weeks.33Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(10):837-49. e19. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002. This is in concurrence with the AAPD Position Statement on its use for caries arrestment and the AAPD chairside guide on SDF in the management of caries lesions.40American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the use of silver diamine fluoride for pediatric dental patients. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2022:72-5. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_SilverDiamine.pdf.,41American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Chairside Guide: Silver Diamine Fluoride in the Management of Dental Caries Lesions. Pediatr Dent 2018;40(6):492-3. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/R_ChairsideGuide.pdf.

Caries removal is not required prior to application of SDF, which is relatively easy and painless.42Torres PJ, Phan HT, Bojorquez AK et al. Minimally Invasive Techniques Used for Caries Management in Dentistry. A Review. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2021;45(4):224-32. doi: 10.17796/1053-4625-45.4.2. Patients/parents must be informed of staining associated with SDF and provide written informed consent prior to treatment.41American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Chairside Guide: Silver Diamine Fluoride in the Management of Dental Caries Lesions. Pediatr Dent 2018;40(6):492-3. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/R_ChairsideGuide.pdf. The acceptability of stain is higher for posterior than anterior teeth and for parents when a child’s cooperation is lacking during treatment, information was provided ahead of time and the alternative was general anesthesia.43Crystal YO, Janal MN, Hamilton DS, Niederman R. Parental perceptions and acceptance of silver diamine fluoride staining. J Am Dent Assoc 2017;148(7):510-8.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2017.03.013.,44Sabbagh H, Othman M, Khogeer L et al. Parental acceptance of silver Diamine fluoride application on primary dentition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2020;20(1):227. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01195-3. A two-step product with application of SDF followed by potassium iodide is also available – while prioritized over SDF alone for root caries due to the minimized risk of staining, this was not the case for coronal caries.33Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(10):837-49. e19. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002.

In a recent systematic review (2022) of 35 RCT, SDF demonstrated greater efficacy than NaFV in arresting dentinal caries.35Cabalén MB, Molina GF, Bono A, Burrow MF. Nonrestorative Caries Treatment: A Systematic Review Update. Int Dent J 2022;72(6):746-64. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2022.06.022. In an umbrella review published in 2019, caries arrestment ranged from 65% to over 90% with use of SDF and was superior to NaFV, atraumatic restorative therapy, and placebo in arresting caries lesions in the primary dentition.45Seifo N, Cassie H, Radford JR, Innes NPT. Silver diamine fluoride for managing carious lesions: an umbrella review. BMC Oral Health 2019;19(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0830-5. SDF is not indicated for teeth with cavitated caries lesions that are encroaching on the pulp, when pain is present or when there is pulpal inflammation.40American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the use of silver diamine fluoride for pediatric dental patients. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2022:72-5. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_SilverDiamine.pdf.,41American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Chairside Guide: Silver Diamine Fluoride in the Management of Dental Caries Lesions. Pediatr Dent 2018;40(6):492-3. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/R_ChairsideGuide.pdf.

Conclusions

Caries prevention and management must consider individual patient factors, risk, benefit, preferences and values. A periodic CRA is recommended, starting at the age one visit. CRA forms part of the clinical decision-making and collaborative process in agreeing on preventive care and interventions. In addition, several CRA tools now offer proposed individualized recommendations for patient care based on the patient’s level.10Featherstone JDB, Alston P, Chaffee BW, Rechmann P. Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA)*: An Update for Use in Clinical Practice for Patients Aged Through Adult. In: CAMBRA® Caries Management by Risk Assessment A Comprehensive Caries Management Guide for Dental Professionals. (2019) https://www.cdafoundation.org/Portals/0/pdfs/cambra_handbook.pdf.,11Malmö University. Cariogram – Download. https://www.mah.se/fakulteter-och-omraden/Odontologiska-fakulteten/Avdelning-och-kansli/Cariologi/Cariogram/.,12Chapple L, Yonel Z. Oral Health Risk Assessment. Dent Update 2018;45:841-7. Evidence-based recommendations and guidelines for caries prevention and management from the AAPD and ADA detail options to prevent caries lesions and provide non-invasive/minimally invasive interventions to arrest and reverse existing lesions in the pediatric patient population.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global oral health status report. Towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. (2022.) https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence of Total and Untreated Dental Caries Among Youth: United States, 2015–2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db307.htm.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health. Dental Caries in Primary Teeth. Oral Health Surveillance Report, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/OHSR-2019-dental-caries-primary-teeth.html.

- 4.American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Early Childhood Caries (ECC): Classifications, Consequences, and Preventive Strategies. 2016. https://www.aapd.org/media/policies_guidelines/p_eccclassifications.pdf.

- 5.Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;25(3):17030.

- 6.Ricketts D, Chadwick G, Hall A. Management of dental caries. In: Advanced operative dentistry: A practical approach. (2011) Ch 1, p1-15. Rickets D, Bartlett D (eds). Elsevier Ltd.

- 7.American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Caries-risk Assessment and Management for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Latest revision, 2019. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/BP_CariesRiskAssessment.pdf.

- 8.American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age 0-6). https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/oral-health-topics/ada_caries_risk_assessment.pdf?rev=35c455eadb104d02aee629ed58513d0b&hash=B0DCCECEDB4349E9D67F75D77CA720AD.

- 9.American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age >6). https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/oral-health-topics/topic_caries_over6.pdf?rev=c5b718b48dd644958d9482c96ab8e874&hash=C4B61882C2A4AB23DEE58D1D5A7417D3.

- 10.Featherstone JDB, Alston P, Chaffee BW, Rechmann P. Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA)*: An Update for Use in Clinical Practice for Patients Aged Through Adult. In: CAMBRA® Caries Management by Risk Assessment A Comprehensive Caries Management Guide for Dental Professionals. (2019) https://www.cdafoundation.org/Portals/0/pdfs/cambra_handbook.pdf.

- 11.Malmö University. Cariogram – Download. https://www.mah.se/fakulteter-och-omraden/Odontologiska-fakulteten/Avdelning-och-kansli/Cariologi/Cariogram/.

- 12.Chapple L, Yonel Z. Oral Health Risk Assessment. Dent Update 2018;45:841-7.

- 13.Twetman S, Banerjee A. Caries Risk Assessment (2020). In: Chapple I, Papapanou P. (eds) Risk Assessment in Oral Health. Springer, Cham.

- 14.U.S. Public Health Service Recommendation for Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Water for the Prevention of Dental Caries. Public Health Rep 2015;130(4):318-31.

- 15.American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride therapy, revised 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/bp_fluoridetherapy.pdf

- 16.American Dental Association. Fluoride: Topical and Systemic Supplements. https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral%20health-topics/fluoride-topical-and-systemic-supplements.

- 17.Wright JT, Hanson N, Ristic H et al. Fluoride toothpaste efficacy and safety in children younger than 6 years. J Am Dent Assoc 2014;145(2):182-9.

- 18.Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo T et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: Executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4581720/.

- 19.Cruz RA, Rolla G. A scanning electron microscope investigation of calcium fluoride-like material deposited during topical fluoride exposure on sound human enamel in vitro. Braz J Med Biol Res 1994;27(10):2371-7.

- 20.Arends J, Christoffersen J. Nature and role of loosely bound fluoride in dental caries. J Dent Res 1990;69(Spec Iss):601-5.

- 21.Saxegaard E, Lagerlöf F, Rølla G. Dissolution of calcium fluoride in human saliva. Acta Odontol Scand 1988;46(6):355-9.

- 22.Tenuta LM, Cerezetti RV, Del Bel Cury AA et al. Fluoride release from CaF2 and enamel demineralization. J Dent Res 2008;87(11):1032-6.

- 23.Hamilton IR. Biochemical effects of fluoride on oral bacteria. J Dent Res 1990;69(special issue):660-7.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fluoride Recommendations Work Group. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001;50(RR-14):1-42.

- 25.American Association of Pediatric Dentists. Dental growth and development. Reference Manual V30/N6/18/19. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/r_dentalgrowth.pdf.

- 26.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Federal Panel on Community Water Fluoridation. U.S. Public Health Service Recommendation for Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Water for the Prevention of Dental Caries. Public Health Reports July–August 2015;130:318-31.

- 27.Levy SM, Broffitt B, Marshall TA et al. Associations between fluorosis of permanent incisors and fluoride intake from infant formula, other dietary sources and dentifrice during early childhood. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141:1190–201.

- 28.Heilman JR, Kiritsy MC, Levy SM, Wefel JS. Assessing fluoride levels of carbonated soft drinks. J Am Dent Assoc 1999;130(11):1593-9.

- 29.Berg J, Gerweck C, Hujoel PP et al. Evidence-based clinical recommendations regarding fluoride intake from reconstituted infant formula and enamel fluorosis. J Am Dent Assoc 2011;142(1):79-87.

- 30.American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Oral Health Policies & Recommendations (The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry). Use of Pit-and-Fissure Sealants (2016). https://www.aapd.org/research/oral-health-policies–recommendations/pit_and_fissure_sealants/.

- 31.American Dental Association. Pit-and-Fissure Sealants Clinical Practice Guideline (2016). https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/evidence-based-dental-research/sealants-clinical-practice-guideline.

- 32.Ferreira Zandona AG, Ritter AV, Eidson RS. Dental caries: Etiology, caries risk assessment, and management. Ch2, p43. In: Ritter AV, Boushell LW, Walter R. Sturdevant’s art & science of operative dentistry-e-book. 7th Ed. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2017.

- 33.Slayton RL, Urquhart O, Araujo MWB et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on nonrestorative treatments for carious lesions: A report from the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc 2018;149(10):837-49. e19. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.07.002.

- 34.Urquhart O, Tampi MP, Pilcher L et al. Nonrestorative Treatments for Caries: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J Dent Res 2019;98(1):14-26. doi: 10.1177/0022034518800014.

- 35.Cabalén MB, Molina GF, Bono A, Burrow MF. Nonrestorative Caries Treatment: A Systematic Review Update. Int Dent J 2022;72(6):746-64. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2022.06.022.

- 36.American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Restorative Dentistry, 2016. https://www.aapd.org/assets/1/7/G_Restorative1.PDF.

- 37.Faghihian R, Shirani M, Tarrahi MJ, Zakizade M. Efficacy of the Resin Infiltration Technique in Preventing Initial Caries Progression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr Dent 2019;41(2):88-94.

- 38.American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Minimally Invasive Dentistry, Adopted 2023. https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/p_minimallyinvasivedentistry.pdf.

- 39.Paris S, Hopfenmuller W, Meyer-Lueckel H. Resin infiltration of caries lesions: An efficacy randomized trial. J Dent Res 2010;89(8):823-6.

- 40.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on the use of silver diamine fluoride for pediatric dental patients. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2022:72-5. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/P_SilverDiamine.pdf.

- 41.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Chairside Guide: Silver Diamine Fluoride in the Management of Dental Caries Lesions. Pediatr Dent 2018;40(6):492-3. https://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/R_ChairsideGuide.pdf.

- 42.Torres PJ, Phan HT, Bojorquez AK et al. Minimally Invasive Techniques Used for Caries Management in Dentistry. A Review. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2021;45(4):224-32. doi: 10.17796/1053-4625-45.4.2.

- 43.Crystal YO, Janal MN, Hamilton DS, Niederman R. Parental perceptions and acceptance of silver diamine fluoride staining. J Am Dent Assoc 2017;148(7):510-8.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2017.03.013.

- 44.Sabbagh H, Othman M, Khogeer L et al. Parental acceptance of silver Diamine fluoride application on primary dentition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2020;20(1):227. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01195-3.

- 45.Seifo N, Cassie H, Radford JR, Innes NPT. Silver diamine fluoride for managing carious lesions: an umbrella review. BMC Oral Health 2019;19(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0830-5.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Fiona-Collins-thumbnail-1-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/09/An-Update-on-Caries-Prevention-and-Management-for-Pediatric-Patients.jpg)