Botox and Dentistry

Botox contains onabotulinumtoxinA, a botulinum toxin protein serotype A (BTX-A) derived from Clostridium botulinum, together with sodium chloride and human albumin.1Small R. Botulinum Toxin Injection for Facial Wrinkles. Am Fam Physician 2014;90(3):168-175. Two additional BTX-A drugs (abobotulinumtoxinA; incobotulinumtoxinA) and a BTX serotype B drug are available.1Small R. Botulinum Toxin Injection for Facial Wrinkles. Am Fam Physician 2014;90(3):168-175.,2Kwon K-H, Shin KS, Yeon SH, Kwon DG. Application of botulinum toxin in maxillofacial field: part I. Bruxism and square jaws. Maxillofacial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2019;41:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-019-0218-0. Dosage, approved indications and clinical data vary by specific drug.3Giordano CN, Matarasso SL, Ozog DM. Injectable and topical neurotoxins in dermatology: Basic science, anatomy, and therapeutic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76(6):1013-1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.022. The focus of this article is on Botox, which was first approved as a therapeutic in 1989 and in 2002 for a cosmetic indication.4Allergan. FDA approves BOTOX® (onabotulinumtoxina) for pediatric patients with lower limb spasticity, excluding spasticity caused by cerebral palsy.. Press Release. 10.24.2019. Available at: https://www.allergan.com/News/Details/2019/10/FDA%20Approves%20BOTOX%20onabotulinumtoxinA%20for%20Pediatric%20Patients%20with%20Lower%20Limb%20Spasticity%20Excluding%20Sp. It is marketed as Botox Cosmetic for cosmetic indications.

Indications

Botox is currently FDA-approved for 11 therapeutic indications. These include the treatment of certain causes of overactive bladder or urinary incontinence; treatment of upper/lower limb spasticity, cervical dystonia, or severe axillary hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating) in adults; prophylaxis of headaches in adults with chronic migraine; treatment of strabismus, or blepharospasm associated with dystonia, in patients age 12 and older; and, treatment of upper limb spasticity in 2- to 17-year-olds.5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf. Full details on indications are provided in the prescribing information.5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf. Botox Cosmetic is FDA-approved in adults for the temporary improvement in the appearance of moderate to severe glabellar, lateral canthal and forehead lines (dynamic wrinkles associated with repeated muscle movement).6Allergan. Prescribing Information. Revised 11/19. Available at: https://media.allergan.com/actavis/actavis/media/allergan-pdf-documents/product-prescribing/20190626-BOTOX-Cosmetic-Insert-72715US10-Med-Guide-v2-0MG1145.pdf. All other uses are off-label.

Contraindications and Drug Interactions

Botox is contraindicated for individuals who are hypersensitive to an ingredient in the formulation or in the presence of infection at the intended injection site.5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf. It is also contraindicated for intradetrusor injection in patients with a urinary tract infection or in patients with urinary retention or post-void residual urine volume >200 mL who are not routinely performing clean intermittent self-catheterization.5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf. Co-administration with other agents affecting neuromuscular transmission, or with aminoglycosides, can potentiate its effect. In addition, excessive muscle weakness may be exacerbated if a muscle relaxant is being used, while using anticholinergic drugs after Botox may have a potentiating effect.5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf. Botox is a Category C drug and is not recommended during pregnancy or lactation.

Mechanisms of Action

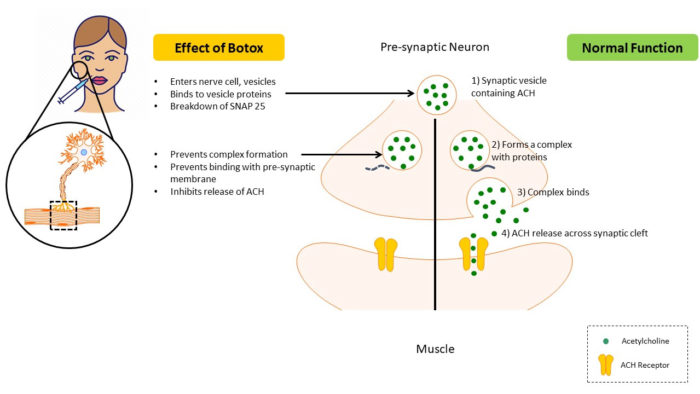

Botox is an acetylcholine (ACH) release inhibitor and neuromuscular blocking agent.5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf. In normal function, neurotransmission at the neuromuscular junction occurs after soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor activating protein receptor (SNARE) proteins, including SNAP-25, form a complex with the synaptic vesicle. This complex then binds to the presynaptic membranes, after which ACH is released and attaches to ACH-receptors on muscle cells. When BTX-A is administered, it attaches to surface receptors on the nerve cell membrane and enters the cell through endocytosis. Next, toxin components bind to vesicle proteins and the toxin’s light-chain component causes breakdown of SNAP-25. As a result, the synaptic vesicle cannot bind to the presynaptic membrane, inhibiting the release of ACH.7Lu AY, Yeung JT, Gerrard JL, Michaelides EM, Sekula RF Jr., Bulsara KR. Hemifacial spasm and neurovascular compression. Scientific World J 2014:349319.

doi: 10.1155/2014/349319.

,8Rusnak JM, Smith LA. Botulism neurotoxins. Section IV, p451-466. In: Manual of Security Sensitive Microbes and Toxins. 2014. ed. Dongyou Liu. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. Boca Raton. The resulting decrease in muscular activity lasts for between 3 and 6 months.5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf.,7Lu AY, Yeung JT, Gerrard JL, Michaelides EM, Sekula RF Jr., Bulsara KR. Hemifacial spasm and neurovascular compression. Scientific World J 2014:349319.

doi: 10.1155/2014/349319.

,9Freud B, Schwartz M, Symington J. The use of botulinum toxin for the treatment of temporomandibular disorders: Preliminary findings. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999;57:916-920. (Figure 1) Muscle relaxation may help eliminate trigger points and pain by locally increasing vascularity.10Kwon K-H, Shin KS, Yeon SH, Kwon DG. Application of botulinum toxin in maxillofacial field: Part II. Wrinkle, intraoral ulcer, and cranio-maxillofacial pain. Maxillofacial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2019;41:42.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-019-0224-2.

Botox may also block release of inflammatory mediators, and inhibit a receptor involved in inflammatory hyperalgesia.8Rusnak JM, Smith LA. Botulism neurotoxins. Section IV, p451-466. In: Manual of Security Sensitive Microbes and Toxins. 2014. ed. Dongyou Liu. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. Boca Raton.,11Ernberg M, Hedenberg-Magnusson B, List T, Svensson P. Efficacy of botulinum toxin type A for treatment of persistent myofascial TMD pain: a randomized, controlled, double-blind multicenter study. Pain 2011;152(9):1988-1996. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.03.036.,12Wei J, Zhu X, Yang G, Shen J, Xie P, Zuo X, Xia L, Han Q, Zhao Y. The efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in treatment of trigeminal neuralgia and peripheral neuropathic pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Brain Behav 2019;9(10):e01409. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1409. ,13Dolly JO, Lawrence GW, Meng J, Wang J, Ovsepian SV. Neuro-exocytosis: botulinum toxins as inhibitory probes and versatile therapeutics. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2009;9(3):326-335. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.03.004.

Off-label uses in the orofacial region

Botox is administered to treat a variety of off-label orofacial conditions, including bruxism, temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD) and myofascial pain, trigeminal and post-herpetic neuralgia, hemifacial spasm, excessive gingival display, benign bilateral masseteric hypertrophy, sialorrhea and to reduce wrinkles in the lower face. (Table 1)

| Table 1. Off-label uses of Botox for treatment in the orofacial region |

|---|

| Bruxism |

| TMD and myofascial pain |

| Trigeminal and post-herpetic neuralgia |

| Excessive gingival display (soft-tissue related) |

| Hemifacial spasm |

| Benign bilateral masseteric hypertrophy |

| Sialorrhea |

| Oromandibular dystonia (focal dystonia) |

| Reduction of perioral/lower face dynamic wrinkles |

Bruxism

Several reviews have been conducted evaluating Botox for the treatment of bruxism. In one systematic review, it was found that reduced pain, occlusal force and the frequency of bruxism episodes occurred following Botox injections into the masseter and/or temporalis muscles.14Fernández-Núñez T, Amghar-Maach S, Gay-Escoda C. Efficacy of botulinum toxin in the treatment of bruxism: Systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2019;24(4):e416-e424. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22923. (Figure 2) This was concluded to be safe, and more effective than placebo or conventional therapy. In an earlier review of 3 randomized controlled trials (RCT) and 2 before-after studies, pain and jaw stiffness were reduced based on subjective evaluation, while no objective reduction in pain or frequency of sleep bruxism episodes was found in 2 studies.15De la Torre Canales G, Câmara-Souza MB, do Amaral CF, Garcia RC, Manfredini D. Is there enough evidence to use botulinum toxin injections for bruxism management? A systematic literature review. Clin Oral Investig 2017;21(3):727-734. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2092-4. In a Phase 4 double-blind RCT in adults with sleep bruxism, no significant between-group difference in subjective pain scores was found 4 to 8 weeks after administration of Botox or placebo into the masseter and temporalis muscles.16Ondo WG, Simmons JH, Shahid MH, Hashem V, Hunter C, Jankovic J. Onabotulinum toxin-A injections for sleep bruxism: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurology 2018;90(7):e559-e564. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004951. However, increased total sleep time and decreased frequency and duration of sleep bruxism was reported. In an earlier study, significant reductions in pain were found at 2 weeks and up to 6 months following Botox administration into the masseter muscles.17Asutay F, Atalay Y, Asutay H, Acar AH. The evaluation of the clinical effects of botulinum toxin on nocturnal bruxism. Pain Research and Management 2017;Article ID 6264146, 5 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6264146. It was concluded that this could be an alternative treatment in patients non-responsive to conservative therapy.

TMD and myofascial pain

In a 2019 review of 7 studies evaluating treatment for TMD-associated myofascial pain, no significant difference in outcome was found for Botox compared to placebo (saline) in 4 studies.18Awan KH, Patil S, Alamir AWH, Maddur N, Arakeri G, Carrozzo M, Brennan PA. Botulinum toxin in the management of myofascial pain associated with temporomandibular dysfunction. J Oral Pathol Med 2019;48(3):192-200. doi: 10.1111/jop.12822. In two of the 3 remaining studies, significant improvements were found with reduced myofascial pain, one of which found Botox, dry needling and lidocaine to be equally effective. Due to cost considerations, it was suggested that Botox be reserved for refractory cases.19Venancio Rde A, Alencar FG Jr, Zamperini C. Botulinum toxin, lidocaine, and dry-needling injections in patients with myofascial pain and headaches. Cranio 2009;27(1):46-53. The third study used a different BTX-A drug.20Guarda-Nardini L, Stecco A, Stecco C, Masiero S, Manfredini D. Myofascial pain of the jaw muscles: comparison of short-term effectiveness of botulinum toxin injections and fascial manipulation technique. Cranio 2012;30(2):95-102. In another systematic review, treatment was found to be well-tolerated and more effective than conventional TMD and low-level laser therapy at 1, 6 and 12 months.21Machado D, Martimbianco ALC, Bussadori SK, Pacheco RL, Riera R, Santos EM. Botulinum toxin type A for painful temporomandibular disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain 2019 Sep 9. pii: S1526-5900(19)30793-X. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.08.011. [Epub ahead of print] In a prospective study, bilateral administration of Botox into the masseter muscles reduced self-reported referred pain in the temporal region and frequency of pain episodes.22Pihut M, Ferendiuk E, Szewczyk M, Kasprzyk K, Wieckiewicz M. The efficiency of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of masseter muscle pain in patients with temporomandibular joint dysfunction and tension-type headache. J Headache Pain 2016;17:29. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0621-1. In another study, Botox was administered to patients who were non-responsive to medication, physical therapy and occlusal splint therapy, and was found to be effective.23Sipahi Calis A, Colakoglu Z, Gunbay S. The use of botulinum toxin-a in the treatment of muscular temporomandibular joint disorders. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2019;120(4):322-325. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2019.02.015 No side effects were reported at 6 months. It was concluded that this was a viable treatment option for non-responsive patients.

Trigeminal and post-herpetic neuralgia

In a review of 10 studies on the efficacy of BTX-A in reducing post-herpetic neuralgia, 6 of 10 studies evaluated Botox.24Jabbari B. Botulinum toxin treatment in post herpetic neuralgia a review. J Bacteriol Mycol 2019;6(2):1098. Only one was a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Significant reductions in post-herpetic pain were observed in all six studies, with no serious adverse events. In a randomized, placebo-controlled study not included in that review, treatment with Botox was found to significantly reduce pain, allodynia and pain thresholds to cold compared to placebo from 2 to 14 weeks post-treatment.25Ranoux D, Attal N, Morain F, Bouhassira D. Botulinum toxin type A induces direct analgesic effects in chronic neuropathic pain. Annals of Neurology, Wiley, 2008, 64 (3), pp.274-83. ff10.1002/ana.21427ff. ffinserm-00292356f. Other than transient pain at injection sites, no adverse events were reported. Reductions in pain associated with trigeminal neuralgia are also found, while not all studies specified which BTX-A was used.12Wei J, Zhu X, Yang G, Shen J, Xie P, Zuo X, Xia L, Han Q, Zhao Y. The efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in treatment of trigeminal neuralgia and peripheral neuropathic pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Brain Behav 2019;9(10):e01409. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1409. ,26Shackleton T, Ram S, Black M, Ryder J, Clark GT, Enciso R. The efficacy of botulinum toxin for the treatment of trigeminal and post-herpetic neuralgia: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2016;122(1):61-71. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.03.003.,27Shehata HS, El‐Tamawy M S, Shalaby N M, Ramzy G. Botulinum toxin‐type A: Could it be an effective treatment option in intractable trigeminal neuralgia? The Journal of Headache and Pain 2013;14, 92 10.1186/1129-2377-14-92

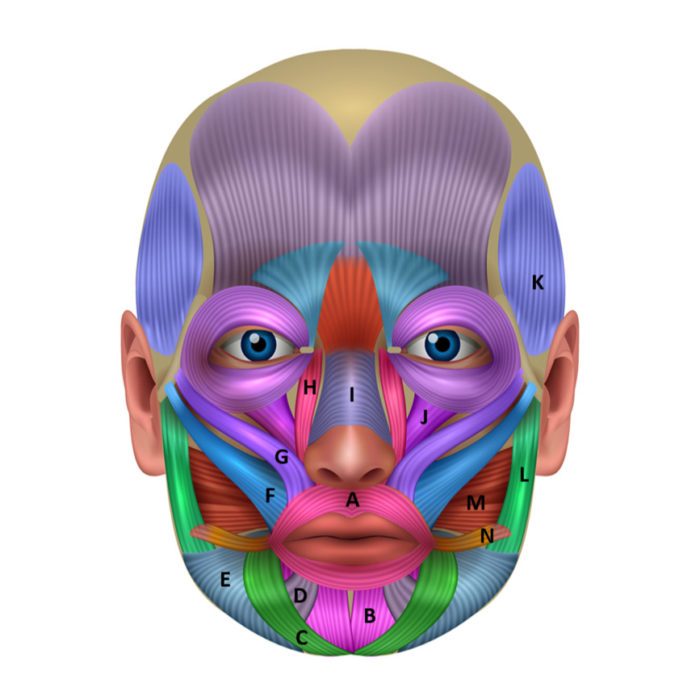

Figure 2.Peri-oral and facial muscles, off-label indications

A: orbicularis oris (radial lip lines); B: Mentalis (deep labiomental fold); C: Depressor anguli oris (downturned smile and lines); D: Depressor labii inferioris (chin lines); E: Platysma; F: Zygomaticus major (posterior gummy smile); G: Zygomaticus minor (posterior gummy smile); H: Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (anterior gummy smile and nasolabial fold); I: Nasalis; J: Levator labii superioris (contributes to gummy smile); K: Temporalis (bruxism, myofascial pain); L: Masseter (bruxism, myofascial pain, benign masseter muscle hypertrophy); M: Buccinator; N: Risorius.

Excessive gingival display

Botox can be used to treat excessive gingival display (gummy smile) associated with anterior maxillary muscle activity or, in the case of posterior gummy smiles, with zygomaticus major and minor muscle activity.28Suber JS, Dinh TP, Prince MD, Smith PD. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of a “gummy smile”. Aesthet Surg J 2014;34(3):432-437. doi: 10.1177/1090820X14527603.,29Delpachitra SN, Sklavos AW, Dastaran M. Clinical uses of botulinum toxin A in smile aesthetic modification. Br Dent J 2018;225(6):502-506. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.755. (Figure 2) This has been shown to be a safe, effective, and minimally-invasive method compared to surgical procedures, albeit requiring repeat treatment.

Benign masseter muscle hypertrophy

Botox can be used to decrease muscle mass as a minimally invasive alternative to surgery for this condition. Individual studies and reports have confirmed reductions in muscle mass.2Kwon K-H, Shin KS, Yeon SH, Kwon DG. Application of botulinum toxin in maxillofacial field: part I. Bruxism and square jaws. Maxillofacial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2019;41:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-019-0218-0.

Other conditions

Hemifacial spasm involves involuntary unilateral contractions of the muscles innervated by the facial nerve.7Lu AY, Yeung JT, Gerrard JL, Michaelides EM, Sekula RF Jr., Bulsara KR. Hemifacial spasm and neurovascular compression. Scientific World J 2014:349319.

doi: 10.1155/2014/349319.

Botox has been used with high success rates to treat this condition for approximately four decades and is considered standard medical care as an alternative to surgery. It is also used to treat oromandibular dystonia, a focal dystonia with involuntary movement and tremors of the lower face. Successful treatment with oral medication has been elusive. The use of BTX-A is considered the treatment of choice, although additional controlled studies are needed.30Comella CL. Systematic review of botulinum toxin treatment for oromandibular dystonia. Toxicon 2018;147:96-99. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.02.006. Sialorrhea (hypersalivation/drooling) may be treated using Botox. In a recent review of the literature, it was concluded that Botox is the best option instead of surgical procedures and an alternative to anticholinergics. It can be effective for 2 to 6 months or longer, depending on the dose. It was also noted that more research is required.31Oliveira AF Filho, Silva GA, Almeida DM. Application of botulinum toxin to treat sialorrhea in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: a literature review. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2016;14(3):431-434. doi:10.1590/S1679-45082016RB3594.

Treatment of dynamic wrinkles

Botox is used off-label to reduce perioral/lower facial dynamic wrinkles. This include wrinkles associated with the orbicularis oris (radial lip lines), depressor anguli oris (downturned smile and lines), levator labii superioris alaeque nasi (nasolabial fold) and/or mentalis muscle (deep labiomental fold).29Delpachitra SN, Sklavos AW, Dastaran M. Clinical uses of botulinum toxin A in smile aesthetic modification. Br Dent J 2018;225(6):502-506. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.755. (Figure 2) Botox is effective in reducing facial dynamic wrinkles.

Potential Complications and Adverse Reactions

Localized, transient reactions at injection sites include discomfort during administration, and transient mild erythema, swelling and tenderness.1Small R. Botulinum Toxin Injection for Facial Wrinkles. Am Fam Physician 2014;90(3):168-175. Bruising can be minimized by applying ice-packs.2Kwon K-H, Shin KS, Yeon SH, Kwon DG. Application of botulinum toxin in maxillofacial field: part I. Bruxism and square jaws. Maxillofacial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2019;41:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-019-0218-0. Transient local drug effects following injection into adjacent muscles include a droopy eyelid/brow, frontal headache and facial asymmetry.1Small R. Botulinum Toxin Injection for Facial Wrinkles. Am Fam Physician 2014;90(3):168-175.,5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf.,6Allergan. Prescribing Information. Revised 11/19. Available at: https://media.allergan.com/actavis/actavis/media/allergan-pdf-documents/product-prescribing/20190626-BOTOX-Cosmetic-Insert-72715US10-Med-Guide-v2-0MG1145.pdf. ,32Kassir M, Gupta M, Galadari H, Kroumpouzos G, Katsambas A, Lotti T, Vojvodic A, Grabbe S, Juchems E, Goldust M. Complications of botulinum toxin and fillers: A narrative review. J Cosmet Dermatol 2019 Dec 30. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13266. Hematoma may occur if a blood vessel is perforated.29Delpachitra SN, Sklavos AW, Dastaran M. Clinical uses of botulinum toxin A in smile aesthetic modification. Br Dent J 2018;225(6):502-506. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.755.

Distant spread can result in serious adverse events, including generalized muscle weakness, difficult speech, and swallowing and breathing difficulties that may be life threatening.5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf. The risk is considered likely greatest in treatment for limb spasticity or if a predisposing condition is present, e.g., a neuromuscular disorder or difficulty swallowing/breathing.5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf. Allergic reactions have been reported.5U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information. BOTOX. Reference ID: 4452114. Revised 6/2019. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103000s5232lbl.pdf. In less than 1% of patients, antibodies to Botox may develop, making treatment ineffective. No definitive serious adverse event reports of distant spread of toxin have been reported at recommended doses for approved cosmetic indications.6Allergan. Prescribing Information. Revised 11/19. Available at: https://media.allergan.com/actavis/actavis/media/allergan-pdf-documents/product-prescribing/20190626-BOTOX-Cosmetic-Insert-72715US10-Med-Guide-v2-0MG1145.pdf. (Table 2)

| Table 2. Potential Complications, Adverse Reactions |

|---|

| Localized discomfort at the time of administration |

| Localized mild erythema, swelling, tenderness, bruising |

| Transient local drug effects, e.g., droopy eyelid/ brow, frontal headache, and facial asymmetry |

| Hematoma if blood vessel perforated |

| Distant spread with serious adverse events |

| Allergic reactions |

| Development of antibodies |

Dental Professionals, Patients and Regulations

Demand for Botox is high, especially for cosmetic procedures.33American Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2018 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. Available at: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2018/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2018.pdf. Dental professionals are very knowledgeable on applied head and neck anatomy and factors influencing esthetics.29Delpachitra SN, Sklavos AW, Dastaran M. Clinical uses of botulinum toxin A in smile aesthetic modification. Br Dent J 2018;225(6):502-506. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.755. Administration of Botox by dental professionals may thus be considered logical, provided appropriate training and education has been obtained. Treatment may include therapeutic or therapeutic-esthetic uses, or strictly cosmetic treatment offered/requested by patients. While dentists and other healthcare professionals can prescribe and administer drugs off-label, safety and efficacy data for the specific off-label use should be evident. As with other treatment, patients must be advised on treatment options, potential risks and benefits, and a written consent form obtained.

State Dental Board regulations vary greatly. For example, under the California Dental Practice Act, dentists can provide therapeutic treatment, and treatment that is both therapeutic and cosmetic as part of a comprehensive dental plan.34California Dental Association. Dentists’ use of Botox requires appropriate dental treatment plan documentation. Dental Practice, August 05, 2019. Available at: https://www.cda.org/Home/News-and-Events/Newsroom/Article-Details/dentists-use-of-botox-requires-appropriate-dental-treatment-plan-documentation-1. Dental hygienists are prohibited from administering Botox. Further, the provision of stand-alone cosmetic treatment under dentistry in California is only permitted for oral surgeons who hold an Elective Facial Cosmetic Surgery permit. In contrast, some States have no regulations other than that the dentist has fulfilled specified training and education requirements and in some States dental hygienists may also administer Botox. Providing treatment that is not permitted under a clinician’s applicable Dental Practice Act can result in enforcement actions and incurs liability not covered by insurance.34California Dental Association. Dentists’ use of Botox requires appropriate dental treatment plan documentation. Dental Practice, August 05, 2019. Available at: https://www.cda.org/Home/News-and-Events/Newsroom/Article-Details/dentists-use-of-botox-requires-appropriate-dental-treatment-plan-documentation-1.

Conclusions

Dental professionals may provide treatment with Botox within their scope of practice. However, treatment in the lower face is all off-label and safety and efficacy data for a given treatment should be available. Researchers have noted the need for more robust studies for off-label orofacial indications, including the off-label uses discussed in this article, to provide an evidence base and clinical guidance.12Wei J, Zhu X, Yang G, Shen J, Xie P, Zuo X, Xia L, Han Q, Zhao Y. The efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in treatment of trigeminal neuralgia and peripheral neuropathic pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Brain Behav 2019;9(10):e01409. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1409. ,15De la Torre Canales G, Câmara-Souza MB, do Amaral CF, Garcia RC, Manfredini D. Is there enough evidence to use botulinum toxin injections for bruxism management? A systematic literature review. Clin Oral Investig 2017;21(3):727-734. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2092-4.,19Venancio Rde A, Alencar FG Jr, Zamperini C. Botulinum toxin, lidocaine, and dry-needling injections in patients with myofascial pain and headaches. Cranio 2009;27(1):46-53.,22Pihut M, Ferendiuk E, Szewczyk M, Kasprzyk K, Wieckiewicz M. The efficiency of botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of masseter muscle pain in patients with temporomandibular joint dysfunction and tension-type headache. J Headache Pain 2016;17:29. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0621-1.,25Ranoux D, Attal N, Morain F, Bouhassira D. Botulinum toxin type A induces direct analgesic effects in chronic neuropathic pain. Annals of Neurology, Wiley, 2008, 64 (3), pp.274-83. ff10.1002/ana.21427ff. ffinserm-00292356f. There is high demand for Botox as a safe and effective treatment to reduce dynamic wrinkles. Clinicians must know and understand what is permitted under their Dental Practice Act, adhere to this, and obtain appropriate training before providing permitted treatment.

References

- 1.Zimmerli B, Jeger F, Lussi A. Bleaching of nonvital teeth. A clinically relevant literature review. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed 2010;120(4):306-20.

- 2.Brunton PA, Burke FJT, Sharif MO et al. Contemporary dental practice in the UK in 2008: Aspects of direct restorations, endodontics, and bleaching. Br Dent J 2012;212:63-7.

- 3.Demarco FF, Conde MCM, Ely C et al. Preferences on vital and nonvital tooth bleaching: A survey among dentists from a city of Southern Brazil. Braz Dent J 2013;24:527-31.

- 4.Kahler B. Present status and future directions – Managing discoloured teeth. Int Endod J 2022: Feb 21. doi: 10.1111/iej.13711.

- 5.Nutting EB, Poe GS. Chemical bleaching of discolored endodontically treated teeth. Dent Clin N Am 1967;11:655-62.

- 6.Pallarés-Serrano A, Pallarés-Serrano S, Pallarés-Serrano A, Pallarés-Sabater A. Assessment of Oxygen Expansion during Internal Bleaching with Enamel and Dentin: A Comparative In Vitro Study. Dent J 2021;9:98. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9090098.

- 7.Estay J, Angel P, Bersezio C et al. The change of teeth color, whiteness variations and its psychosocial and self-perception effects when using low vs. high concentration bleaching gels: a one-year follow-up. BMC Oral Health 2020;20(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01244-x.

- 8.Haywood VB, Bergeron BE. Bleaching and the Diagnosis of Internal Resorption. Jul 24, 2018. https://decisionsindentistry.com/article/bleaching-and-the-diagnosis-of-internal-resorption/

- 9.Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x.

- 10.Sakalli B, Basmaci F, Dalmizrak O. Evaluation of the penetration of intracoronal bleaching agents into the cervical region using different intraorifice barriers. BMC Oral Health 2022;22(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02300-4.

- 11.American Association of Endodontists Clinical Practice Committee. Use of Silver Points. AAE Position Statement. https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/06/silverpointsstatement.pdf#:~:text=Silver%20points%20have%20been%20shown%20to%20corrode%20spontaneously,retreatment%20and%20replacement%20of%20the%20points%20with%20another.

- 12.Savadkouhi ST, Fazlyab M. Discoloration Potential of Endodontic Sealers: A Brief Review. Iran Endod J 2016;11(4):250-4. doi: 10.22037/iej.2016.20.

- 13.Ahmed HM, Abbott PV. Discolouration potential of endodontic procedures and materials: a review. Int Endod J 2012;45(10):883-97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02071.x.

- 14.Krastl G, Allgayer N, Lenherr P et al. Tooth discoloration induced by endodontic materials: a literature review. Dent Traumatol 2013;29(1):2-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2012.01141.x.

- 15.Ioannidis K, Mistakidis I, Beltes P, Karagiannis V. Spectrophotometric analysis of crown discoloration induced by MTA- and ZnOE-based sealers. J Appl Oral Sci 2013;21(2):138-44. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757201302254.

- 16.Santos LGPD, Chisini LA, Springmann CG et al. Alternative to Avoid Tooth Discoloration after Regenerative Endodontic Procedure: A Systematic Review. Braz Dent J 2018;29(5):409-18. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201802132.

- 17.Watts A, Addy M. Tooth discoloration and staining: a review of the literature. Br Dent J 2001;190:309-16.

- 18.Pink tooth of Mummery. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Pink+Tooth+of+Mummery.

- 19.Haywood VB. History, safety, and effectiveness of current bleaching techniques and applications of the nightguard vital bleaching technique. Quintessence Int 1992:23:471-88. http://www.quintpub.com/userhome/qi/qi_23_7_haywood_6.pdf

- 20.Bersezio C, Ledezma P, Mayer C et al. Effectiveness and effect of non-vital bleaching on the quality of life of patients up to 6 months post-treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2018;22(9):3013-9. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2389-y.

- 21.Popescu AD, Purcarea MV, Georgescu RV et al. Vital and Non-Vital Tooth Bleaching Procedures: A Survey Among Dentists From Romania. Rom J Oral Rehab 2021;13(3):59-71. https://www.rjor.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/VITAL-AND-NON-VITAL-TOOTH-BLEACHING-PROCEDURES-A-SURVEY-AMONG-DENTISTS-FROM-ROMANIA.pdf.

- 22.Zarean P, Zarean P, Ravaghi A et al. Comparison of MTA, CEM Cement, and Biodentine as Coronal Plug during Internal Bleaching: An In Vitro Study. Int J Dent 2020;2020:8896740. doi: 10.1155/2020/8896740.

- 23.Canoglu E, Gulsahi K, Sahin C et al. Effect of bleaching agents on sealing properties of different intraorifice barriers and root filling materials. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2012;17 (4):e710-5. http://www.medicinaoral.com/medoralfree01/v17i4/medoralv17i4p710.pdf

- 24.Amato A, Caggiano M, Pantaleo G, Amato M. In-office and walking bleach dental treatments on endodontically-treated teeth: 25 years follow-up. Minerva Stomatol 2018;67(6):225-30.

- 25.Lim MY, Lum SOY, Poh RSC et al. An in vitro comparison of the bleaching efficacy of 35% carbamide peroxide with established intracoronal bleaching agents. Int Endod J 2004;37(7):483-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00829.x.

- 26.Yui KCK, Rodrigues JR, Mancini MNG et al. Ex vivo evaluation of the effectiveness of bleaching agents on the shade alteration of blood-stained teeth. Int Endod J 2008;41(6):485-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01379.x.

- 27.Warren MA, Wong M, Ingram TA III. An in vitro comparison of bleaching agents on the crowns and roots of discolored teeth. J Endod 1990;16:463-7.

- 28.Rotstein I, Mor C, Friedman S. Prognosis of intracoronal bleaching with sodium perborate preparations in vitro: 1-year study. J Endod 1993;19:10-2.

- 29.Weiger R, Kuhn A, Lost C. In vitro comparison of various types of sodium perborate used for intracoronal bleaching of discolored teeth. J Endod 1994;20:338-41.

- 30.Amato M, Scaravilli MS, Farella M, Riccitiello F. Bleaching teeth treated endodontically: long-term evaluation of a case series. J Endod 2006;32:376-8.

- 31.Abou-Rass M. Long-term prognosis of intentional endodontics and internal bleaching of tetracycline-stained teeth. Compend Contin Educ Dent 1998;19:1034-44.

- 32.Anitua E, Zabalegui B, Gil J, Gascon F. Internal bleaching of severe tetracycline discolorations: four-year clinical evaluation. Quintessence Int 1990;21(10):783-8.

- 33.Gorr S-U, Brigman HV, Anderson JC, Hirsch EB. The antimicrobial peptide DGL13K is active against drug-resistant gram-negative bacteria and sub-inhibitory concentrations stimulate bacterial growth without causing resistance. PLoS ONE 2022;17(8): e0273504. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273504.

- 34.Peters SM, Hill NB, Halepas S. Oral manifestations of monkeypox: A report of two cases Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2022.07.147.

- 35.Portalatin A. Infectious disease experts call on dentists to monitor monkeypox symptoms: 6 notes. August 15, 2022. https://www.beckersdental.com/clinical-leadership-infection-control/39124-infectious-disease-experts-call-on-dentists-to-monitor-monkeypox-symptoms-6-notes.html?origin=DentalE&utm_source=DentalE&utm_medium=email&utm_content=newsletter&oly_enc_id=1694C1316967A3F.

- 36.CDC. Monkeypox. Non-Variola Orthopoxvirus and Monkeypox Virus Laboratory Testing Data. August 17, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/2022-lab-test.html.

- 37.CDC. Monkeypox. Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/prevention.html.

- 38.CDC. Monkeypox and smallpox vaccine guidance. Updated June 2, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/index.htm.

- 39.CDC. Monkeypox. ACAM Vaccine. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/interim-considerations/acam2000-vaccine.html.

- 40.CDC. Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings — 2003. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5217.pdf.

- 41.CDC. Infection Prevention and Control of Monkeypox in Healthcare Settings. Updated August 11, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/infection-control-healthcare.html

- 42.CDC. Monkeypox. Information For Veterinarians. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/veterinarian/index.html.

- 43.CDC. Monkeypox. Pets in the Home. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/prevention/pets-in-homes.html.

- 44.Cheng YL, Musonda J, Cheng H, et al. Effect of surface removal following bleaching on the bond strength of enamel. BMC Oral Health 2019;19(1):50.

- 45.Monteiro D, Moreira A, Cornacchia T, Magalhães C. Evaluation of the effect of different enamel surface treatments and waiting times on the staining prevention after bleaching. J Clin Exp Dent 2017;9(5):e677-81.

- 46.Rezende M, Kapuchczinski AC, Vochikovski L, et al. Staining power of natural and artificial dyes after at-home dental bleaching. J Contemp Dent Pract 2019;20(4):424-7.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Fiona-Collins-thumbnail-1-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2020/03/Botox-and-Dentistry-2.jpg)