Culture and Cultural Competency

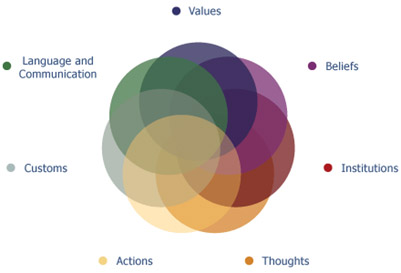

Figure 1. Elements of culture

Source: Cultural Competency Program for Oral Health Professionals! The Office of Minority Health of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

Culture is defined as ‘the integrated pattern of human behavior that includes thoughts, communications, actions, customs/traditions, beliefs, values and institutions of a racial, ethnic, religious or social group.’1Cross T, Bazron BJ, Dennis KW, Isaacs MR. Toward a culturally competent system of care. Washington, DC: CAASP Technical Assistance Center, Georgetown University Child Development Center; National Center for Cultural Competence. Conceptual frameworks/models, guiding values and principles. Washington, DC. Available at: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED330171.pdf. (Figure 1) Each of us grew up in a culture and lives in a culture which may be different to the one we were first familiar with. In addition, diversity occurs within one group and language and communication are bound with culture.2Cultural Competency Program for Oral Health Professionals! The Office of Minority Health of the Department of Health and Human Services. While linguistic competency is also important for patients with limited English proficiency or low/no literacy skills, the focus of this article is on cultural competency.2Cultural Competency Program for Oral Health Professionals! The Office of Minority Health of the Department of Health and Human Services. Culture influences oral health beliefs, diet, behaviors, access to care, the use of healthcare services and potentially health outcomes.3Forsyth CJ, Irving MJ, Tennant M, Short SD, Gilroy JA. Teaching Cultural Competence in Dental Education: A Systematic Review and Exploration of Implications for Indigenous Populations in Australia. J Dent Educ 2017;81(8):956-68. doi: 10.21815/JDE.017.049. Culture is a factor in health disparities, with minority and indigenous populations bearing a greater burden of disease.3Forsyth CJ, Irving MJ, Tennant M, Short SD, Gilroy JA. Teaching Cultural Competence in Dental Education: A Systematic Review and Exploration of Implications for Indigenous Populations in Australia. J Dent Educ 2017;81(8):956-68. doi: 10.21815/JDE.017.049.

Culture, Oral Health Beliefs and Behaviors

Cultural beliefs among specific groups include that it is inevitable you will lose your teeth, children will develop cavities and that the primary dentition does not matter.4Butani Y, Weintraub JA, Barker JC. Oral health-related cultural beliefs for four racial/ethnic groups: Assessment of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2008;8:26. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-8-26 Among Hispanics/Latinos tooth loss may be viewed as a natural part of aging.5Riley JL, Gilbert GH, Heft MW. Dental attitudes: Proximal basis for oral health disparities in adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2006;34:289-98. Within some cultures, it is also believed that dental care during pregnancy can damage the fetus.6Gaffield ML, Colley-Gilbert BJ, Malvitz DM, Romaguera R. Oral health during pregnancy: An analysis of information collected by the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. J Am Dent Assoc 2001;132:1009-16.,7Bahramian H, Mohebbi SZ, Khami MR, Quinonez RB. Qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators of dental service utilization of pregnant women: A triangulation approach. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2018;18:Article number 153. In other cultures, the extraction or alteration of teeth is a ritual or rite-of-passage.8Pinchi V, Barbieri P, Pradella F, Focardi M, Bartolini V, Norelli G-A. Dental ritual mutilations and forensic odontologist practice: a review of the literature. Acta Stomatol Croat 2015;49(1):3-13. In the Indian sub-continent it is believed that paan and gutkha, which are variants of smokeless tobacco, offer health benefits, when in fact their use is associated with oral cancer and a high incidence of oral submucous fibrosis.9Niaz K, Maqbool F, Khan F, Bahadar H, Ismail Hassan F, Abdollahi M. Smokeless tobacco (paan and gutkha) consumption, prevalence, and contribution to oral cancer. Epidemiol Health 2017;39:e2017009. This demonstrates the relevance of culture to oral health. Knowledge of beliefs and behaviors, therefore, enables improved communication and care for patients. Patients can be asked about their oral health beliefs and to convey what has been communicated to them (the talk-back method). In addition, materials can be tailored for the individual patient, including written and visual materials.

Barriers to Care

The belief that tooth loss is normal, or that the primary dentition does not matter, functions as a barrier to care as individuals may not seek timely care. Poor cultural competency can also result in patient failure to utilize dental or medical services. In one study, lack of utilization was found for parents who reported being dissatisfied with care that had previously been provided.4Butani Y, Weintraub JA, Barker JC. Oral health-related cultural beliefs for four racial/ethnic groups: Assessment of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2008;8:26. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-8-26 Further, in a study of Chinese individuals living in the United Kingdom, communication problems and cultural beliefs were found to be barriers to care.10Kwan SY, Williams SA. Attitudes of Chinese people toward obtaining dental care in the UK. Br Dent J 1998;185:188-91.Communication itself varies across cultures in style, personal space, touch and gestures.

Figure 2. Perceptions among dentists on culture, language, or both as a barrier to care11Da Costa EP, Lee JY, Rozier RG, Zeldin L. Dental care for pregnant women. An assessment of North Carolina general dentists. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141(8):986-94.

Cultural barriers exist for both healthcare professionals and patients. In one study, 99% of dentists responded in a survey that routine preventive dental care should be provided to women who are pregnant, while responses differed with respect to restorative and other care.11Da Costa EP, Lee JY, Rozier RG, Zeldin L. Dental care for pregnant women. An assessment of North Carolina general dentists. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141(8):986-94. Barriers to care cited by dentists included differences in culture, language, or both. Forty-eight percent, 19.2% and 32.9% responded that they agreed/strongly agreed, were not sure, or disagreed/strongly disagreed, respectively, that these are barriers to care. (Figure 2) In addition, some dentists report discomfort in treating pregnant women.12Lee RS, Milgrom P, Huebner CE, Conrad DA. Dentists’ perceptions of barriers to providing dental care to pregnant women. Womens Health Issues 2010;20:359-65. Another example is the role of parental attitudes and concerns, some of which are related to religious and cultural norms, as barriers to HPV vaccination for teenagers.13Hariri S, Unger ER, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, Swan D, Patel S, Markowitz LE. Prevalence of genital Human Papillomavirus among females in the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003– 2006. J Infect Dis 2011;204:566-73.,14Ferrer HB, Trotter C, Hickman M, Audrey S. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination of young women in high-income countries: a qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health 2014;14:700.

Cultural Dissonance and Cultural Competency

Cultural dissonance occurs when an individual experiences a ‘sense of discord, disharmony, confusion, or conflict experienced by people in the midst of change in their cultural environment.’15Cultural Dissonance. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_dissonance. For example, cultural dissonance can be experienced by patients, immigrant parents and children, and in areas where help is needed and is provided without understanding or considering local beliefs. Patients may prefer traditional medicine and still receive this care while also accessing modern medicine.16Bengiamin M, Chang X, Capitaman JA. Understanding traditional Hmong health and prenatal care beliefs, practices, utilization and needs. 2011. Available at: www.cvhpi.org. Further, in one study it was found that younger immigrants were more trusting of dental professionals than their parents who had been older at the time of immigration and who would have preferred a dentist of Chinese origin.10Kwan SY, Williams SA. Attitudes of Chinese people toward obtaining dental care in the UK. Br Dent J 1998;185:188-91.

Cultural competency is considered a key component in addressing diverse patient groups and in reducing oral health disparities.3Forsyth CJ, Irving MJ, Tennant M, Short SD, Gilroy JA. Teaching Cultural Competence in Dental Education: A Systematic Review and Exploration of Implications for Indigenous Populations in Australia. J Dent Educ 2017;81(8):956-68. doi: 10.21815/JDE.017.049. At an individual level, cultural competency can be defined as ‘A person’s ability to understand and interact with people from cultures and backgrounds other than their own.’17American Dental Education Association. Need for diversity. Available at: https://www.adea.org/godental/dentistry_101/need for diversity.aspx. Cultural competency at an institutional and healthcare system level is also required, and refers to an organizational capacity to communicate and work effectively in cross-cultural situations. Attributes of cultural competency include learning about cultures and gaining experiences, awareness, valuing diversity, avoiding stereotypes and being engaged with the communities around you.18U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health [HHS OMH]. National standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health and health care: A blueprint for advancing and sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice. 2013. Available at: https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas. (Figure 3)

Learning and Improving Cultural Competency

Numerous initiatives and interventions have been undertaken in healthcare, including in the dental setting, to help improve cultural competency with the ultimate objective of improving access to care and health outcomes. In one recent initiative, Hispanic caregivers from an Early Head Start program were trained in prenatal and children’s oral health and then conducted culturally competent workshops as community oral health workers in their local community.19Villalta J, Askaryar H, Verzemnieks I, Kinsler J, Kropenske V, Ramos-Gomez F. Developing an effective community oral health workers: “Promotoras” model for Early Head Start. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00175. It was found that this improved knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding oral health, oral care and fluoridated water. The longer-term goal is to reduce early childhood caries.

Outreach with real-life experience is recognized as an important factor in cultural awareness and competency.20Finbarr A. Embedding a population oral health perspective in the dental curriculum. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2012;40(Suppl 2):127-33. In a recent systematic review of 12 studies with more than 1300 participants, the cultural competence of dental students was improved by community service-learning as well as reflective writing on students’ experiences, and seminars.3Forsyth CJ, Irving MJ, Tennant M, Short SD, Gilroy JA. Teaching Cultural Competence in Dental Education: A Systematic Review and Exploration of Implications for Indigenous Populations in Australia. J Dent Educ 2017;81(8):956-68. doi: 10.21815/JDE.017.049. Community-based clinical experience provides dental care to diverse disadvantaged individuals and provides an opportunity for students to improve their communication skills and cultural competency.21Johnson BR, Loomer PM, Siegel SC, Pilcher ES, Leigh JE, Gillespie MJ, Simmons RK, Turner SP. Strategic partnerships between academic dental institutions and communities: addressing disparities in oral health care. J Am Dent Assoc 2007;138(10):1366-71.,22Ramos-Gomez FJ, Silva DR, Law CS, Pizzitola RL, John B, Crall JJ. Creating a new generation of pediatric dentists: a paradigm shift in training. J Dent Educ 2014;78(12):1593-603. In one study, students worked in diverse communities prior to entering dental school. This experience was found to result in greater awareness of patient diversity and health equity/social justice in healthcare.23Behar-Horenstein LS, Feng X, Roberts KW, Gibbs M, Catalanotto FA, Hudson-Vassell CM. Developing dental students' awareness of health care disparities and desire to serve vulnerable populations through service-learning. J Dent Educ 2015;79(10):1189-200.

In an evaluation of healthcare professional education, a single workshop was found to improve confidence in the ability to communicate with Aboriginal patients in a culturally competent manner.24Durey A, Halkett G, Berg M, Lester L, Kickett M. Does one workshop on respecting cultural differences increase health professionals’ confidence to improve the care of Australian Aboriginal patients with cancer? An evaluation. BMC Health Services Research 2017;17:Article number 660. Awareness of barriers to care and methods to provide healthcare in a culturally appropriate manner improved, and perceptions of this patient group changed. Improvements were still reported 2 months after the workshop and it was suggested that ongoing education could be beneficial. Mobile dental clinics have also been used in dental education, whereby students can provide care in the community and underserved individuals can receive care.21Johnson BR, Loomer PM, Siegel SC, Pilcher ES, Leigh JE, Gillespie MJ, Simmons RK, Turner SP. Strategic partnerships between academic dental institutions and communities: addressing disparities in oral health care. J Am Dent Assoc 2007;138(10):1366-71.

Findings on Outcomes of Interventions

Several reviews have evaluated the outcomes of interventions conducted to improve cultural competency. In one review, studies involving individuals with disabilities, the LGBT population and racial and ethnic minorities were included. Interventions identified included those intended to improve cultural competence of care, provider training/education, changes or delivery of an existing protocol and those that would prompt patients to access the healthcare system or providers.25Butler M, McCreedy E, Schwer N, Burgess D, Call K, Przedworski J, Rosser S, Larson S, Allen M, Fu S, Kane RL. Improving cultural competence to reduce health disparities [Internet]. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016 Mar. Report No.:16-EHC006-EF. Two reviews found a low level of evidence indicating that there was no long-term effect on treatment outcomes following cultural competency training. Weaknesses of studies included non-randomization, poor follow-up and unintended consequences not being reported. In a scoping review conducted in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, 64 studies from 2006 to 2015 were included of which 16 addressed provider interventions for cultural competency and professional development.26Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R. Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):232. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3001-5. Improved practitioner knowledge, skills and attitudes/beliefs were reported for 9, 7 and 5 of the 16 studies, respectively. However, health outcomes were only reported for 2 studies and healthcare for 6. (Figure 4) It was concluded that there was a scarcity of information on positive health and healthcare outcomes and that measures on the impact of interventions on these are required.

In another systematic review, a lack of evidence was found for cultural competency interventions and their impact on healthcare for indigenous populations.27Clifford A, McCalman J, Bainbridge R, Tsey K. Interventions to improve cultural competency in health care for Indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2015;27(2):89-98. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv010. Further, in an earlier report of this scoping review, it was noted that the most frequently reported outcome was the acceptability of the intervention to patients.28Jongen CS, McCalman J, Bainbridge RG. The implementation and evaluation of health promotion services and programs to improve cultural competency: A systematic scoping review. Front Public Health 2017;5:24. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00024. Five studies reported on patient satisfaction, only one used a validated measurement tool to evaluate this parameter and only two reported greater patient satisfaction following the intervention.

Conclusions

Cultural competency training has been proposed as a way to improve patient outcomes.29Lie DA, Lee-Rey E, Gomez A, Bereknyei S, Braddock CH 3rd. Does cultural competency training of health professionals improve patient outcomes? A systematic review and proposed algorithm for future research. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26(3):317-25. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1529-0. It has, however, been recommended that validated measurement tools be used and more thorough research conducted on how culture influences oral health and health outcomes, to provide an evidence base for cultural competency interventions.4Butani Y, Weintraub JA, Barker JC. Oral health-related cultural beliefs for four racial/ethnic groups: Assessment of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2008;8:26. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-8-26,12Lee RS, Milgrom P, Huebner CE, Conrad DA. Dentists’ perceptions of barriers to providing dental care to pregnant women. Womens Health Issues 2010;20:359-65.,26Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R. Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):232. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3001-5.,27Clifford A, McCalman J, Bainbridge R, Tsey K. Interventions to improve cultural competency in health care for Indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2015;27(2):89-98. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv010.,30Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Review 2000:57:Supplement 1:181-217. One proposal has been to use a standardized framework where outcomes are segmented into intermediate outcomes such as patient satisfaction, access to care, and improved knowledge and health behaviors and health outcomes measured as reductions in disease and improvements in health and quality of life.30Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Review 2000:57:Supplement 1:181-217. In addition, clear identification of groups in studies and more research on agency and system level approaches for meeting the service needs of diverse populations are recommended.4Butani Y, Weintraub JA, Barker JC. Oral health-related cultural beliefs for four racial/ethnic groups: Assessment of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2008;8:26. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-8-26,31Delphin-Rittmon ME, Andres-Hyman R, Flanagan EH, Davidson L. Seven essential strategies for promoting and sustaining systemic cultural competence. Psychiatr Q 2013;84(1):53-64. doi: 10.1007/s11126-012-9226-2. Cultural competence is an important skill for healthcare professionals given that it is recognized as a factor in the delivery of healthcare, for health outcomes and to address oral health disparities. Preferred intervention methodologies include community-based research approaches, culturally tailored strategies, and the use of community workers to deliver initiatives.32Tiwari T, Jamieson L, Broughton J, Lawrence HP, Batliner TS, Arantes R, Albino J. Reducing indigenous oral health inequalities: A review from 5 nations. J Dent Res 2018;97(8):869-77. doi: 10.1177/0022034518763605.

References

- 1.Cross T, Bazron BJ, Dennis KW, Isaacs MR. Toward a culturally competent system of care. Washington, DC: CAASP Technical Assistance Center, Georgetown University Child Development Center; National Center for Cultural Competence. Conceptual frameworks/models, guiding values and principles. Washington, DC. Available at: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED330171.pdf.

- 2.Cultural Competency Program for Oral Health Professionals! The Office of Minority Health of the Department of Health and Human Services.

- 3.Forsyth CJ, Irving MJ, Tennant M, Short SD, Gilroy JA. Teaching Cultural Competence in Dental Education: A Systematic Review and Exploration of Implications for Indigenous Populations in Australia. J Dent Educ 2017;81(8):956-68. doi: 10.21815/JDE.017.049.

- 4.Butani Y, Weintraub JA, Barker JC. Oral health-related cultural beliefs for four racial/ethnic groups: Assessment of the literature. BMC Oral Health 2008;8:26. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-8-26

- 5.Riley JL, Gilbert GH, Heft MW. Dental attitudes: Proximal basis for oral health disparities in adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2006;34:289-98.

- 6.Gaffield ML, Colley-Gilbert BJ, Malvitz DM, Romaguera R. Oral health during pregnancy: An analysis of information collected by the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. J Am Dent Assoc 2001;132:1009-16.

- 7.Bahramian H, Mohebbi SZ, Khami MR, Quinonez RB. Qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators of dental service utilization of pregnant women: A triangulation approach. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2018;18:Article number 153.

- 8.Pinchi V, Barbieri P, Pradella F, Focardi M, Bartolini V, Norelli G-A. Dental ritual mutilations and forensic odontologist practice: a review of the literature. Acta Stomatol Croat 2015;49(1):3-13.

- 9.Niaz K, Maqbool F, Khan F, Bahadar H, Ismail Hassan F, Abdollahi M. Smokeless tobacco (paan and gutkha) consumption, prevalence, and contribution to oral cancer. Epidemiol Health 2017;39:e2017009.

- 10.Kwan SY, Williams SA. Attitudes of Chinese people toward obtaining dental care in the UK. Br Dent J 1998;185:188-91.

- 11.Da Costa EP, Lee JY, Rozier RG, Zeldin L. Dental care for pregnant women. An assessment of North Carolina general dentists. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141(8):986-94.

- 12.Lee RS, Milgrom P, Huebner CE, Conrad DA. Dentists’ perceptions of barriers to providing dental care to pregnant women. Womens Health Issues 2010;20:359-65.

- 13.Hariri S, Unger ER, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, Swan D, Patel S, Markowitz LE. Prevalence of genital Human Papillomavirus among females in the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003– 2006. J Infect Dis 2011;204:566-73.

- 14.Ferrer HB, Trotter C, Hickman M, Audrey S. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination of young women in high-income countries: a qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health 2014;14:700.

- 15.Cultural Dissonance. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_dissonance.

- 16.Bengiamin M, Chang X, Capitaman JA. Understanding traditional Hmong health and prenatal care beliefs, practices, utilization and needs. 2011. Available at: www.cvhpi.org.

- 17.American Dental Education Association. Need for diversity. Available at: https://www.adea.org/godental/dentistry_101/need for diversity.aspx.

- 18.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health [HHS OMH]. National standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health and health care: A blueprint for advancing and sustaining CLAS Policy and Practice. 2013. Available at: https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas.

- 19.Villalta J, Askaryar H, Verzemnieks I, Kinsler J, Kropenske V, Ramos-Gomez F. Developing an effective community oral health workers: “Promotoras” model for Early Head Start. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00175.

- 20.Finbarr A. Embedding a population oral health perspective in the dental curriculum. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2012;40(Suppl 2):127-33.

- 21.Johnson BR, Loomer PM, Siegel SC, Pilcher ES, Leigh JE, Gillespie MJ, Simmons RK, Turner SP. Strategic partnerships between academic dental institutions and communities: addressing disparities in oral health care. J Am Dent Assoc 2007;138(10):1366-71.

- 22.Ramos-Gomez FJ, Silva DR, Law CS, Pizzitola RL, John B, Crall JJ. Creating a new generation of pediatric dentists: a paradigm shift in training. J Dent Educ 2014;78(12):1593-603.

- 23.Behar-Horenstein LS, Feng X, Roberts KW, Gibbs M, Catalanotto FA, Hudson-Vassell CM. Developing dental students' awareness of health care disparities and desire to serve vulnerable populations through service-learning. J Dent Educ 2015;79(10):1189-200.

- 24.Durey A, Halkett G, Berg M, Lester L, Kickett M. Does one workshop on respecting cultural differences increase health professionals’ confidence to improve the care of Australian Aboriginal patients with cancer? An evaluation. BMC Health Services Research 2017;17:Article number 660.

- 25.Butler M, McCreedy E, Schwer N, Burgess D, Call K, Przedworski J, Rosser S, Larson S, Allen M, Fu S, Kane RL. Improving cultural competence to reduce health disparities [Internet]. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016 Mar. Report No.:16-EHC006-EF.

- 26.Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R. Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):232. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3001-5.

- 27.Clifford A, McCalman J, Bainbridge R, Tsey K. Interventions to improve cultural competency in health care for Indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2015;27(2):89-98. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv010.

- 28.Jongen CS, McCalman J, Bainbridge RG. The implementation and evaluation of health promotion services and programs to improve cultural competency: A systematic scoping review. Front Public Health 2017;5:24. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00024.

- 29.Lie DA, Lee-Rey E, Gomez A, Bereknyei S, Braddock CH 3rd. Does cultural competency training of health professionals improve patient outcomes? A systematic review and proposed algorithm for future research. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26(3):317-25. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1529-0.

- 30.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Review 2000:57:Supplement 1:181-217.

- 31.Delphin-Rittmon ME, Andres-Hyman R, Flanagan EH, Davidson L. Seven essential strategies for promoting and sustaining systemic cultural competence. Psychiatr Q 2013;84(1):53-64. doi: 10.1007/s11126-012-9226-2.

- 32.Tiwari T, Jamieson L, Broughton J, Lawrence HP, Batliner TS, Arantes R, Albino J. Reducing indigenous oral health inequalities: A review from 5 nations. J Dent Res 2018;97(8):869-77. doi: 10.1177/0022034518763605.