Endodontically Treated Teeth and the Walking Bleach Technique

The walking bleach technique, also known as internal bleaching, is a popular choice among patients and clinicians for treating discolored endodontically treated teeth.1Zimmerli B, Jeger F, Lussi A. Bleaching of nonvital teeth. A clinically relevant literature review. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed 2010;120(4):306-20.,2Brunton PA, Burke FJT, Sharif MO et al. Contemporary dental practice in the UK in 2008: Aspects of direct restorations, endodontics, and bleaching. Br Dent J 2012;212:63-7.,3Demarco FF, Conde MCM, Ely C et al. Preferences on vital and nonvital tooth bleaching: A survey among dentists from a city of Southern Brazil. Braz Dent J 2013;24:527-31.,4Kahler B. Present status and future directions - Managing discoloured teeth. Int Endod J 2022: Feb 21. doi: 10.1111/iej.13711. The term ‘walking bleach’ was first introduced more than 50 years ago by Nutting and Poe, who modified an earlier technique by using sodium perborate (SP) in combination with 30% hydrogen peroxide (HP) instead of water.5Nutting EB, Poe GS. Chemical bleaching of discolored endodontically treated teeth. Dent Clin N Am 1967;11:655-62.,6Pallarés-Serrano A, Pallarés-Serrano S, Pallarés-Serrano A, Pallarés-Sabater A. Assessment of Oxygen Expansion during Internal Bleaching with Enamel and Dentin: A Comparative In Vitro Study. Dent J 2021;9:98. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9090098. As with vital full-arch tooth whitening, the walking bleach technique has been shown to result in improvements in patients’ perceptions of dental esthetics.7Estay J, Angel P, Bersezio C et al. The change of teeth color, whiteness variations and its psychosocial and self-perception effects when using low vs. high concentration bleaching gels: a one-year follow-up. BMC Oral Health 2020;20(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01244-x. Other non-invasive options for endodontically treated teeth include the single-tooth tray bleaching technique alone or in combination with the walking bleach technique.8Haywood VB, Bergeron BE. Bleaching and the Diagnosis of Internal Resorption. Jul 24, 2018. https://decisionsindentistry.com/article/bleaching-and-the-diagnosis-of-internal-resorption/ More invasive options include crowns and veneers. In this article, we will discuss the etiology of stain in non-vital and endodontically treated teeth, treatment criteria, treatment protocol, and the clinical evidence for treatment outcomes.

Etiology of stain in nonvital and endodontically treated teeth

Single-tooth internal discoloration is associated primarily with trauma, with progressively fewer cases accounted for by prior dental treatment, pulp necrosis and pulp canal calcification. The latter two have the highest propensity to result in dark yellow stains.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x. Endodontically treated teeth may exhibit compromised esthetics due to stain resulting from a variety of reasons. Pulpal tissue remnants, including due to a pulp horn that was missed, and debris in the pulp chamber are potential etiologies for stain.8Haywood VB, Bergeron BE. Bleaching and the Diagnosis of Internal Resorption. Jul 24, 2018. https://decisionsindentistry.com/article/bleaching-and-the-diagnosis-of-internal-resorption/,10Sakalli B, Basmaci F, Dalmizrak O. Evaluation of the penetration of intracoronal bleaching agents into the cervical region using different intraorifice barriers. BMC Oral Health 2022;22(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02300-4. While tetracycline staining may be considered, this would typically also involve other teeth, including the contralateral tooth.

Dental materials can result in staining, including dark yellow stain that is difficult to treat.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x. Silver points were historically used for root canal obturation, however this method has been superseded with the use of modern techniques and it is now recommended that these not be used.11American Association of Endodontists Clinical Practice Committee. Use of Silver Points. AAE Position Statement. https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/06/silverpointsstatement.pdf#:~:text=Silver%20points%20have%20been%20shown%20to%20corrode%20spontaneously,retreatment%20and%20replacement%20of%20the%20points%20with%20another. Furthermore, corrosion associated with silver points in contact with blood and serum was a cause of staining in endodontically treated teeth.

Endodontic sealers can cause discoloration by diffusing into dentinal tubules. In a review of 11 studies published between 2000 and 2015, it was concluded that endodontic sealers induce discoloration to varying extents.12Savadkouhi ST, Fazlyab M. Discoloration Potential of Endodontic Sealers: A Brief Review. Iran Endod J 2016;11(4):250-4. doi: 10.22037/iej.2016.20. The same conclusion was reached in two other reviews.13Ahmed HM, Abbott PV. Discolouration potential of endodontic procedures and materials: a review. Int Endod J 2012;45(10):883-97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02071.x.,14Krastl G, Allgayer N, Lenherr P et al. Tooth discoloration induced by endodontic materials: a literature review. Dent Traumatol 2013;29(1):2-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2012.01141.x. For sealers containing silver, corrosion leads to greyish to blackish stain while those that were used that contained bismuth lead to greenish to blackish stain.12Savadkouhi ST, Fazlyab M. Discoloration Potential of Endodontic Sealers: A Brief Review. Iran Endod J 2016;11(4):250-4. doi: 10.22037/iej.2016.20. Due to the risk for staining, bismuth has been replaced as the component providing for radiopacity by other agents such as zirconium oxide. A high potential for stain induced by resin-based sealers has been observed, while in the only study available on the use of a silicone-based sealer no discoloration was reported, and in another study minimal discoloration was found for sealers containing tricalcium silicate.12Savadkouhi ST, Fazlyab M. Discoloration Potential of Endodontic Sealers: A Brief Review. Iran Endod J 2016;11(4):250-4. doi: 10.22037/iej.2016.20.,15Ioannidis K, Mistakidis I, Beltes P, Karagiannis V. Spectrophotometric analysis of crown discoloration induced by MTA- and ZnOE-based sealers. J Appl Oral Sci 2013;21(2):138-44. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757201302254. Additionally, triple antibiotic paste (containing metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and minocycline) and grey mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) have each been proven to cause discoloration, with an additive effect if both are used.16Santos LGPD, Chisini LA, Springmann CG et al. Alternative to Avoid Tooth Discoloration after Regenerative Endodontic Procedure: A Systematic Review. Braz Dent J 2018;29(5):409-18. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201802132. These materials can be substituted for with double antibiotic paste containing no minocycline and white MTA which does not contain iron.

Lastly, internal and external resorption must be part of the differential diagnosis for stain and would require treatment for the resorption process (if the tooth is not already hopeless).8Haywood VB, Bergeron BE. Bleaching and the Diagnosis of Internal Resorption. Jul 24, 2018. https://decisionsindentistry.com/article/bleaching-and-the-diagnosis-of-internal-resorption/ Either may present initially as a pink spot/area near the cementoenamel junction (CEJ).17Watts A, Addy M. Tooth discoloration and staining: a review of the literature. Br Dent J 2001;190:309-16. When associated with internal resorption, this is also known as the ‘pink tooth of Mummery’.18Pink tooth of Mummery. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Pink+Tooth+of+Mummery. (Table 1) Internal resorption often results in a darkened/greyish area.

| Table 1. Etiology of stains in nonvital and endodontically treated teeth |

|---|

| Trauma |

| Pulp necrosis |

| Pulp canal calcification |

| Pulpal tissue remnants/missed pulp horn |

| Debris in the pulp chamber |

| Endodontic sealers |

| Restorative materials |

| Triple antibiotic paste |

| Grey mineral trioxide aggregate |

| Internal/external resorption |

Diagnosis and Criteria

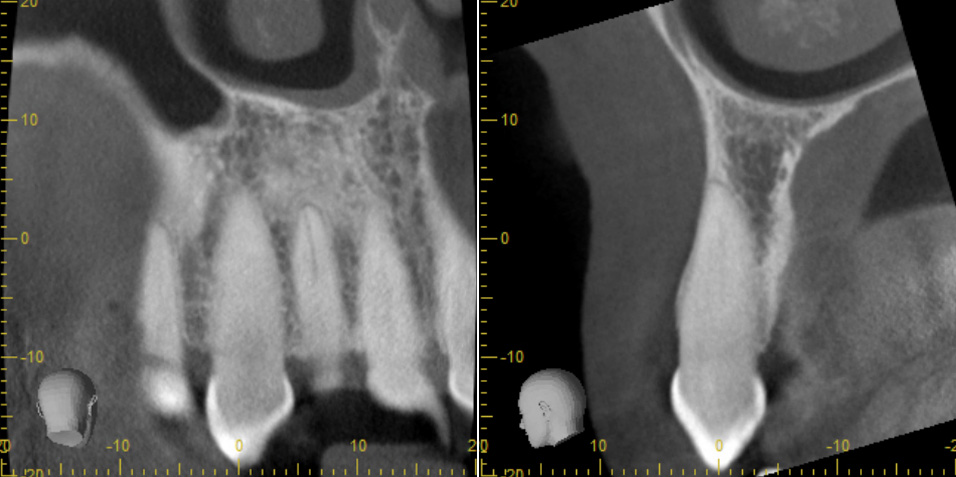

A thorough evaluation, including radiographs and ideally Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT), is necessary to determine appropriate treatment for endodontically treated teeth. Imaging can show anatomical defects, the state of the root canal obturation and health of the apical tissues and contributes to the identification of internal and external resorption. External resorption presents near the CEJ with a concave-shaped, radiolucent defect. If it is accessible, probing will elicit bleeding. If external resorption is present, it may be possible to treat it and to subsequently perform a walking bleach technique. Internal bleaching does not treat enamel stains or defective enamel and is also contraindicated when there is extensive loss of dentin or dental caries is present.

Walking bleach technique

The walking bleach technique has been performed using a variety of bleaching agents. Recent studies have included treatment using 30% or 35% HP, 10% or 37% carbamide peroxide (CP), SP alone mixed with distilled water, or a combination of SP and 30% HP.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x.,19Haywood VB. History, safety, and effectiveness of current bleaching techniques and applications of the nightguard vital bleaching technique. Quintessence Int 1992:23:471-88. http://www.quintpub.com/userhome/qi/qi_23_7_haywood_6.pdf ,20Bersezio C, Ledezma P, Mayer C et al. Effectiveness and effect of non-vital bleaching on the quality of life of patients up to 6 months post-treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2018;22(9):3013-9. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2389-y.,21Popescu AD, Purcarea MV, Georgescu RV et al. Vital and Non-Vital Tooth Bleaching Procedures: A Survey Among Dentists From Romania. Rom J Oral Rehab 2021;13(3):59-71. https://www.rjor.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/VITAL-AND-NON-VITAL-TOOTH-BLEACHING-PROCEDURES-A-SURVEY-AMONG-DENTISTS-FROM-ROMANIA.pdf. SP is a HP-releasing compound. Once a diagnosis has been made and it has been verified that the endodontically treated tooth is suitable for internal bleaching, basic steps in the walking bleach technique are as follows (variations are reported in individual studies):8Haywood VB, Bergeron BE. Bleaching and the Diagnosis of Internal Resorption. Jul 24, 2018. https://decisionsindentistry.com/article/bleaching-and-the-diagnosis-of-internal-resorption/,9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x.,20Bersezio C, Ledezma P, Mayer C et al. Effectiveness and effect of non-vital bleaching on the quality of life of patients up to 6 months post-treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2018;22(9):3013-9. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2389-y.

- Ensure the gutta percha ends apical to the CEJ – 2 mm to 3 mm apical to the CEJ has been recommended, depending on the study.

- Place a barrier 2 to 2.5 mm in thickness immediately coronal to the gutta percha obturation material to seal the area off. A patent seal is mandatory, to prevent and minimize diffusion of peroxide into the dentinal tubules, and the barrier layer should match the contours of the CEJ.

- Materials used as an apical barrier now include calcium silicate-based cements, tricalcium-silicate-based cement, MTA, calcium enriched mixture cement, as well as more traditional materials such as resin composites, glass ionomer and resin-modified glass ionomer cements, and zinc oxide-based materials.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x.,10Sakalli B, Basmaci F, Dalmizrak O. Evaluation of the penetration of intracoronal bleaching agents into the cervical region using different intraorifice barriers. BMC Oral Health 2022;22(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02300-4.,22Zarean P, Zarean P, Ravaghi A et al. Comparison of MTA, CEM Cement, and Biodentine as Coronal Plug during Internal Bleaching: An In Vitro Study. Int J Dent 2020;2020:8896740. doi: 10.1155/2020/8896740.,23Canoglu E, Gulsahi K, Sahin C et al. Effect of bleaching agents on sealing properties of different intraorifice barriers and root filling materials. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2012;17 (4):e710-5. http://www.medicinaoral.com/medoralfree01/v17i4/medoralv17i4p710.pdf

- The barrier material must be completely set before internal bleaching proceeds and depending on the material used it may be necessary to wait a week (with a temporary restoration in place).

- Place the bleaching agent into the pulp chamber and in access against the barrier layer. In a study by Abbott, liquid 37.5% orthophosphoric acid was applied for 30 seconds to etch the access cavity and then thoroughly washed out prior to placement of the bleaching agent.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x. Use of 1%–3% sodium hypochlorite in the access cavity has also been recommended prior to placing the bleaching agent, as has use of alcohol.4Kahler B. Present status and future directions - Managing discoloured teeth. Int Endod J 2022: Feb 21. doi: 10.1111/iej.13711.

- Seal off the access area. Typically, GIC or resin-based composite or a temporary material is used.

- Follow up 5 to 7 days later and assess the shade.

- Replace the bleaching agent and repeat the process if inadequate shade change was obtained. Based on the literature, the process may need to be performed up to 3 to 5 times.

- Once the desired shade is achieved, the temporary material used to cover the access area and the bleaching agent are removed. Since the shear bond strength of materials may be affected temporarily by the bleaching process, it is sometimes recommended to wait approximately 2 weeks before placing the definitive restoration.

In the case shown below, the patient had presented wanting to improve the cosmetic appearance of her upper left canine which was discolored. This discoloration had become more pronounced in recent months. The tooth was asymptomatic and had only minimal responses on pulp testing, consistent with extensive canal space calcification evident radiographically and per the CBCT scan. A history of trauma was the suspected etiology. Options were discussed, and the patient opted for endodontic treatment followed by internal bleaching. During internal bleaching, treatment was provided using SP and a CP gel placed in the pulp chamber after a glass ionomer cement barrier had been placed coronal to the gutta percha inside the canal to just above the CEJ. The process was repeated once after 7 days. As a result of internal bleaching, an excellent shade match was achieved. (Figures 1 - 5)

Case courtesy of Manish Garala, BDS, MS. Diplomate, American Board of Endodontics.

Clinical outcomes

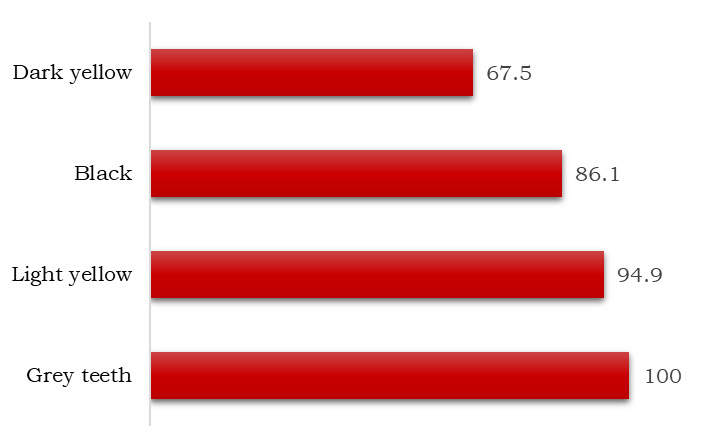

Both long- and short-term results have been reported. In 2018, the results of a study with a follow-up of 25 years were published.24Amato A, Caggiano M, Pantaleo G, Amato M. In-office and walking bleach dental treatments on endodontically-treated teeth: 25 years follow-up. Minerva Stomatol 2018;67(6):225-30. Both in-office intracoronal bleaching and the walking bleach technique were performed utilizing 10% CP gel, with excellent results. At 25 years, good shade match to adjacent teeth was still observed for 85% of patients (34 of 40 teeth). In 2009, a retrospective study was reported with a follow-up period of up to 5 years.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x. Results were available for 225 teeth (203 patients) treated using a paste consisting of 35% HP in combination with SP. For 87.1% of teeth the shade improvement was ‘Good’ (i.e., matched the adjacent teeth perfectly and the patient was very pleased) and was ‘Acceptable’ (i.e., almost a shade match and acceptable to the patient and/or parent) for all remaining treated teeth. (Figure 6) One application was sufficient for up to 75% of teeth with grey or light-yellow staining, while more applications were needed for black stains and especially for teeth with dark yellow stains which were the most challenging. Up to 25% of teeth required between three and five applications.

In a recent randomized clinical study, endodontically treated discolored anterior teeth were treated using 35% HP or 37% CP over 4 sessions and the potential for shade regression evaluated.20Bersezio C, Ledezma P, Mayer C et al. Effectiveness and effect of non-vital bleaching on the quality of life of patients up to 6 months post-treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2018;22(9):3013-9. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2389-y. No statistically significant differences were found for shade changes for HP and CP, respectively. At one year, there was still no significant difference between the results of HP and CP, and minimal shade regression had occurred. It was concluded that the walking bleach technique was effective for both bleaching agents. (Table 2)

Table 2. Results of selected in vivo and in vitro studies

| Author, year | Agents and Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Amato et al (2018)24Amato A, Caggiano M, Pantaleo G, Amato M. In-office and walking bleach dental treatments on endodontically-treated teeth: 25 years follow-up. Minerva Stomatol 2018;67(6):225-30. | Good shade match at 25 years for 85% of patients (34 of 40 teeth) receiving in-office intracoronal bleaching and walking bleach using 10% CP gel. |

| Abbott and Heah (2009)9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x. | Retrospective study of 255 teeth treated with 35% HP in combination with SP. 87.1% of teeth matched adjacent teeth perfectly, shade match for remaining teeth was acceptable. |

| Bersezio et al (2018)20Bersezio C, Ledezma P, Mayer C et al. Effectiveness and effect of non-vital bleaching on the quality of life of patients up to 6 months post-treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2018;22(9):3013-9. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2389-y. | Effective bleaching using 35% HP or 37% CP. No statistically significant differences for shade at one year for HP and CP, and minimal shade regression. |

| Lim et al (2004)25Lim MY, Lum SOY, Poh RSC et al. An in vitro comparison of the bleaching efficacy of 35% carbamide peroxide with established intracoronal bleaching agents. Int Endod J 2004;37(7):483-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00829.x. | In vitro study. At 7 and 14 days, 35% CP, 35% HP and SP mixed with distilled water were equally effective for internal bleaching by day 14. |

| Yui et al (2008)26Yui KCK, Rodrigues JR, Mancini MNG et al. Ex vivo evaluation of the effectiveness of bleaching agents on the shade alteration of blood-stained teeth. Int Endod J 2008;41(6):485-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01379.x. | In vitro study. Effective internal bleaching at days 7 and 14, with no significant difference for SP with either 10% or 35% CP. Significantly reduced shade change for SP mixed with distilled water. |

In an in vitro study, the efficacy of internal bleaching was compared for 35% CP, 35% HP, and SP mixed with distilled water.25Lim MY, Lum SOY, Poh RSC et al. An in vitro comparison of the bleaching efficacy of 35% carbamide peroxide with established intracoronal bleaching agents. Int Endod J 2004;37(7):483-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00829.x. After staining induced by whole blood during root canal treatment, the teeth were obturated and a barrier seal placed. At 7 and 14 days after treatment, 35% CP and 35% HP were equally effective with average shade changes of 8 and 10, respectively. For the SP mix, it took until day 14 for there to be no significant difference in results for the three methods. In a second laboratory experiment, internal bleaching using SP and distilled water was compared to use of SP plus either 10% CP or 35% CP for 21 days, with the bleaching agent replenished at days 7 and 14.26Yui KCK, Rodrigues JR, Mancini MNG et al. Ex vivo evaluation of the effectiveness of bleaching agents on the shade alteration of blood-stained teeth. Int Endod J 2008;41(6):485-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01379.x. No statistically significant difference was found for the number of shade changes (VITA Easyshade) following treatment with SP in combination with 10% or 35% CP. In contrast, a statistically significant reduction in shade change was found for SP mixed with distilled water.26Yui KCK, Rodrigues JR, Mancini MNG et al. Ex vivo evaluation of the effectiveness of bleaching agents on the shade alteration of blood-stained teeth. Int Endod J 2008;41(6):485-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01379.x. In vitro studies conducted between 1990 and 1994 (and earlier) also support the efficacy of SP with distilled water and with between 3% and 30% HP.27Warren MA, Wong M, Ingram TA III. An in vitro comparison of bleaching agents on the crowns and roots of discolored teeth. J Endod 1990;16:463-7. ,28Rotstein I, Mor C, Friedman S. Prognosis of intracoronal bleaching with sodium perborate preparations in vitro: 1-year study. J Endod 1993;19:10-2.,29Weiger R, Kuhn A, Lost C. In vitro comparison of various types of sodium perborate used for intracoronal bleaching of discolored teeth. J Endod 1994;20:338-41.

Shade regression

In a study with a 16-year follow-up period, noticeable shade regression occurred in 37.1% of teeth (n=50).30Amato M, Scaravilli MS, Farella M, Riccitiello F. Bleaching teeth treated endodontically: long-term evaluation of a case series. J Endod 2006;32:376-8. In a more recent study, among those cases that were available for recalls (range 6 months to up to five years), shade regression was present in 3.9% of treated teeth.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x. Repeat internal bleaching was necessary for six teeth, with excellent results. In a study with a longer follow-up, after both in-office intracoronal bleaching and the walking bleach technique with 10% CP gel, shade regression of at least two shades occurred in 15% of patients (6 of 40 teeth) after 25 years.24Amato A, Caggiano M, Pantaleo G, Amato M. In-office and walking bleach dental treatments on endodontically-treated teeth: 25 years follow-up. Minerva Stomatol 2018;67(6):225-30. Earlier studies have also reported shade regression.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x. Causes of shade regression include marginal breakdown of restorations, new extrinsic/intrinsic staining, and breakdown of oxidation products.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x. As with vital bleaching shade regression can be managed, in this case by repeating the walking bleach technique if necessary.

Potential Adverse Events

Early reports of ‘cervical resorption’ in internally bleached teeth attributed this to excessive use of heating instruments during in-office internal bleaching, as well as high concentrations of HP (30%).19Haywood VB. History, safety, and effectiveness of current bleaching techniques and applications of the nightguard vital bleaching technique. Quintessence Int 1992:23:471-88. http://www.quintpub.com/userhome/qi/qi_23_7_haywood_6.pdf Overall, internal bleaching has been reported to account for 3.9% of all cases of external invasive resorption.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x. External resorption, which is poorly understood, in fact occurs apical to the CEJ. It has been proposed that the release of peroxide occurs in teeth with developmental gaps between the enamel and cementum where dentin is exposed, found in around 10% of all teeth, resulting in an inflammatory response.19Haywood VB. History, safety, and effectiveness of current bleaching techniques and applications of the nightguard vital bleaching technique. Quintessence Int 1992:23:471-88. http://www.quintpub.com/userhome/qi/qi_23_7_haywood_6.pdf This theory supports the imperative for a patent seal between the pulp chamber and the obturation material, to prevent peroxide from diffusing out to the cervical area and periodontal tissues.23Canoglu E, Gulsahi K, Sahin C et al. Effect of bleaching agents on sealing properties of different intraorifice barriers and root filling materials. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2012;17 (4):e710-5. http://www.medicinaoral.com/medoralfree01/v17i4/medoralv17i4p710.pdf

In a recent study, no cases of external invasive resorption were observed.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x. No cases of resorption at 16 years were found in a prior study.30Amato M, Scaravilli MS, Farella M, Riccitiello F. Bleaching teeth treated endodontically: long-term evaluation of a case series. J Endod 2006;32:376-8. Similarly in a study in which SP and 30% GP were used in combination for internal bleaching, no external root resorption was observed during a follow-up period ranging from 3 to 15 years.31Abou-Rass M. Long-term prognosis of intentional endodontics and internal bleaching of tetracycline-stained teeth. Compend Contin Educ Dent 1998;19:1034-44. Additionally, in another study with a four-year follow-up, no cases of external resorption were found following internal bleaching with SP alone.32Anitua E, Zabalegui B, Gil J, Gascon F. Internal bleaching of severe tetracycline discolorations: four-year clinical evaluation. Quintessence Int 1990;21(10):783-8. Further adverse events occur in a few cases, including coronal/root fractures that result in the need for crowns or extractions.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x.

It is essential that patients are fully informed of both the benefits and risks of internal bleaching as well as alternative options and that written informed consent is obtained.

Conclusions

Where possible, it is incumbent upon clinicians to prevent iatrogenic discoloration of endodontically treated teeth through judicious removal of pulpal tissues, selection of dental materials including endodontic sealants, and removal of endodontic sealers from the pulp chamber during endodontic treatment. 8Haywood VB, Bergeron BE. Bleaching and the Diagnosis of Internal Resorption. Jul 24, 2018. https://decisionsindentistry.com/article/bleaching-and-the-diagnosis-of-internal-resorption/,9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x.,10Sakalli B, Basmaci F, Dalmizrak O. Evaluation of the penetration of intracoronal bleaching agents into the cervical region using different intraorifice barriers. BMC Oral Health 2022;22(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02300-4.,12Savadkouhi ST, Fazlyab M. Discoloration Potential of Endodontic Sealers: A Brief Review. Iran Endod J 2016;11(4):250-4. doi: 10.22037/iej.2016.20.,13Ahmed HM, Abbott PV. Discolouration potential of endodontic procedures and materials: a review. Int Endod J 2012;45(10):883-97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02071.x.,15Ioannidis K, Mistakidis I, Beltes P, Karagiannis V. Spectrophotometric analysis of crown discoloration induced by MTA- and ZnOE-based sealers. J Appl Oral Sci 2013;21(2):138-44. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757201302254. For endodontically treated teeth that are discolored, the walking bleach technique provides a non-invasive treatment option. In contrast to more invasive methods such as crowns, internal bleaching does not require removal of large amounts of tooth structure, retains the original tooth shape (desirable provided its shape was acceptable), and simplifies treatment.9Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x.,19Haywood VB. History, safety, and effectiveness of current bleaching techniques and applications of the nightguard vital bleaching technique. Quintessence Int 1992:23:471-88. http://www.quintpub.com/userhome/qi/qi_23_7_haywood_6.pdf Recent studies also demonstrate that the potential for shade regression is manageable as is the risk of adverse events. Provided the appropriate steps are taken, outcomes for this technique are reliable, it results in good shade matches and can result in both patient and clinician satisfaction.

References

- 1.Zimmerli B, Jeger F, Lussi A. Bleaching of nonvital teeth. A clinically relevant literature review. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed 2010;120(4):306-20.

- 2.Brunton PA, Burke FJT, Sharif MO et al. Contemporary dental practice in the UK in 2008: Aspects of direct restorations, endodontics, and bleaching. Br Dent J 2012;212:63-7.

- 3.Demarco FF, Conde MCM, Ely C et al. Preferences on vital and nonvital tooth bleaching: A survey among dentists from a city of Southern Brazil. Braz Dent J 2013;24:527-31.

- 4.Kahler B. Present status and future directions - Managing discoloured teeth. Int Endod J 2022: Feb 21. doi: 10.1111/iej.13711.

- 5.Nutting EB, Poe GS. Chemical bleaching of discolored endodontically treated teeth. Dent Clin N Am 1967;11:655-62.

- 6.Pallarés-Serrano A, Pallarés-Serrano S, Pallarés-Serrano A, Pallarés-Sabater A. Assessment of Oxygen Expansion during Internal Bleaching with Enamel and Dentin: A Comparative In Vitro Study. Dent J 2021;9:98. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj9090098.

- 7.Estay J, Angel P, Bersezio C et al. The change of teeth color, whiteness variations and its psychosocial and self-perception effects when using low vs. high concentration bleaching gels: a one-year follow-up. BMC Oral Health 2020;20(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01244-x.

- 8.Haywood VB, Bergeron BE. Bleaching and the Diagnosis of Internal Resorption. Jul 24, 2018. https://decisionsindentistry.com/article/bleaching-and-the-diagnosis-of-internal-resorption/

- 9.Abbott P, Heah SY. Internal bleaching of teeth: an analysis of 255 teeth. Aust Dent J 2009;54(4):326-33. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01158.x.

- 10.Sakalli B, Basmaci F, Dalmizrak O. Evaluation of the penetration of intracoronal bleaching agents into the cervical region using different intraorifice barriers. BMC Oral Health 2022;22(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s12903-022-02300-4.

- 11.American Association of Endodontists Clinical Practice Committee. Use of Silver Points. AAE Position Statement. https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/06/silverpointsstatement.pdf#:~:text=Silver%20points%20have%20been%20shown%20to%20corrode%20spontaneously,retreatment%20and%20replacement%20of%20the%20points%20with%20another.

- 12.Savadkouhi ST, Fazlyab M. Discoloration Potential of Endodontic Sealers: A Brief Review. Iran Endod J 2016;11(4):250-4. doi: 10.22037/iej.2016.20.

- 13.Ahmed HM, Abbott PV. Discolouration potential of endodontic procedures and materials: a review. Int Endod J 2012;45(10):883-97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02071.x.

- 14.Krastl G, Allgayer N, Lenherr P et al. Tooth discoloration induced by endodontic materials: a literature review. Dent Traumatol 2013;29(1):2-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2012.01141.x.

- 15.Ioannidis K, Mistakidis I, Beltes P, Karagiannis V. Spectrophotometric analysis of crown discoloration induced by MTA- and ZnOE-based sealers. J Appl Oral Sci 2013;21(2):138-44. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757201302254.

- 16.Santos LGPD, Chisini LA, Springmann CG et al. Alternative to Avoid Tooth Discoloration after Regenerative Endodontic Procedure: A Systematic Review. Braz Dent J 2018;29(5):409-18. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201802132.

- 17.Watts A, Addy M. Tooth discoloration and staining: a review of the literature. Br Dent J 2001;190:309-16.

- 18.Pink tooth of Mummery. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Pink+Tooth+of+Mummery.

- 19.Haywood VB. History, safety, and effectiveness of current bleaching techniques and applications of the nightguard vital bleaching technique. Quintessence Int 1992:23:471-88. http://www.quintpub.com/userhome/qi/qi_23_7_haywood_6.pdf

- 20.Bersezio C, Ledezma P, Mayer C et al. Effectiveness and effect of non-vital bleaching on the quality of life of patients up to 6 months post-treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2018;22(9):3013-9. doi: 10.1007/s00784-018-2389-y.

- 21.Popescu AD, Purcarea MV, Georgescu RV et al. Vital and Non-Vital Tooth Bleaching Procedures: A Survey Among Dentists From Romania. Rom J Oral Rehab 2021;13(3):59-71. https://www.rjor.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/VITAL-AND-NON-VITAL-TOOTH-BLEACHING-PROCEDURES-A-SURVEY-AMONG-DENTISTS-FROM-ROMANIA.pdf.

- 22.Zarean P, Zarean P, Ravaghi A et al. Comparison of MTA, CEM Cement, and Biodentine as Coronal Plug during Internal Bleaching: An In Vitro Study. Int J Dent 2020;2020:8896740. doi: 10.1155/2020/8896740.

- 23.Canoglu E, Gulsahi K, Sahin C et al. Effect of bleaching agents on sealing properties of different intraorifice barriers and root filling materials. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2012;17 (4):e710-5. http://www.medicinaoral.com/medoralfree01/v17i4/medoralv17i4p710.pdf

- 24.Amato A, Caggiano M, Pantaleo G, Amato M. In-office and walking bleach dental treatments on endodontically-treated teeth: 25 years follow-up. Minerva Stomatol 2018;67(6):225-30.

- 25.Lim MY, Lum SOY, Poh RSC et al. An in vitro comparison of the bleaching efficacy of 35% carbamide peroxide with established intracoronal bleaching agents. Int Endod J 2004;37(7):483-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2004.00829.x.

- 26.Yui KCK, Rodrigues JR, Mancini MNG et al. Ex vivo evaluation of the effectiveness of bleaching agents on the shade alteration of blood-stained teeth. Int Endod J 2008;41(6):485-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01379.x.

- 27.Warren MA, Wong M, Ingram TA III. An in vitro comparison of bleaching agents on the crowns and roots of discolored teeth. J Endod 1990;16:463-7.

- 28.Rotstein I, Mor C, Friedman S. Prognosis of intracoronal bleaching with sodium perborate preparations in vitro: 1-year study. J Endod 1993;19:10-2.

- 29.Weiger R, Kuhn A, Lost C. In vitro comparison of various types of sodium perborate used for intracoronal bleaching of discolored teeth. J Endod 1994;20:338-41.

- 30.Amato M, Scaravilli MS, Farella M, Riccitiello F. Bleaching teeth treated endodontically: long-term evaluation of a case series. J Endod 2006;32:376-8.

- 31.Abou-Rass M. Long-term prognosis of intentional endodontics and internal bleaching of tetracycline-stained teeth. Compend Contin Educ Dent 1998;19:1034-44.

- 32.Anitua E, Zabalegui B, Gil J, Gascon F. Internal bleaching of severe tetracycline discolorations: four-year clinical evaluation. Quintessence Int 1990;21(10):783-8.