Occupational Hearing Loss in Dentistry

Occupational hearing loss can result from exposure to hazardous noise or ototoxic chemicals.1Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Occupational hearing loss (OHL) surveillance. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/ohl/default.html. In the United States, an estimated 22 million individuals are occupationally exposed to hazardous noise and an estimated 3% of workers overall have noise-induced occupational hearing loss (NOHL).2Masterson EA, Bushnell PT, Themann CL, Morata TC. Hearing impairment among noise-exposed workers — United States, 2003–2012. MMWR 2016;65(15):389-94 The dental team is exposed to occupational noise on a daily basis in the course of performing procedures. Concern over the possibility of NOHL among dentists was reported in 1960.3Cantwell KR, Tunturi AR, Manny VR. Noise from high-speed hand-pieces. J Am Dent Assoc 1960;61:571-7. Since then, numerous studies have assessed noise levels and investigated NOHL in the dental setting. Understanding the potential risk for NOHL is important and undertaking mitigation efforts can prevent this condition.

Measuring Noise Levels

Noise levels are typically defined using an A-weighted decibel scale (dbA).4Occupational Safety and Health Administration. How loud is too loud? Occupational noise exposure. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/noisehearingconservation/ This scale is designed to closely match how we perceive loudness, by giving less weight to low and high frequencies. Since the scale is logarithmic, a small change in dbA represents a large change in loudness.4Occupational Safety and Health Administration. How loud is too loud? Occupational noise exposure. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/noisehearingconservation/,5Measurement in decibels: What is the difference between dB and dB(A)? General Acoustics, May 14, 2019. Available at: https://www.softdb.com/difference-between-db-dba/. Hazardous noise is typically defined as a time-weighted average of ≥85 dbA for an 8-hour workday.4Occupational Safety and Health Administration. How loud is too loud? Occupational noise exposure. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/noisehearingconservation/ However, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has a permissible exposure limit of 90 dbA for an 8-hour workday while, based on updated information, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommends <85 dbA.4Occupational Safety and Health Administration. How loud is too loud? Occupational noise exposure. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/noisehearingconservation/ In addition, OSHA allows 4 hours at 95 dbA and 2 hours at 100 dbA daily (halving the time for each 5 dbA increase), while at 100 dBA NIOSH recommends <15 minutes per day (and uses a 3 dbA increase for halving recommended exposure times). While some studies report db (or dbA) SPL rather than dbA, the measured number is considered synonymous at ≥1000 Hz, diverging at lower frequencies.6Chasin M. For whom the decibel tolls: The dBA vs dB SPL war. The Hearing Review, January 2013. Available at: https://www.hearingreview.com/hearing-products/accessories/headphones/for-whom-the-decibel-tolls-the-dba-vs-db-spl-war-january-2013-hearing-review

Hearing loss

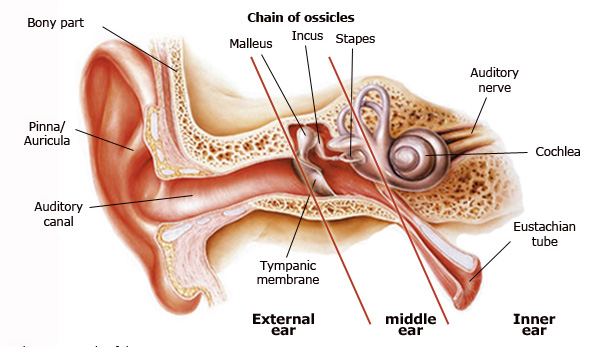

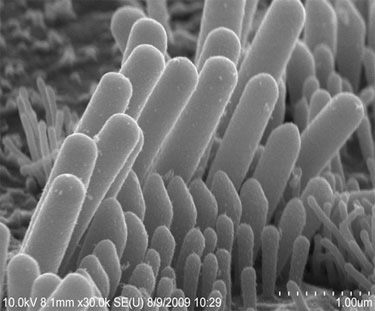

In normal function, when noise occurs and vibrations reach the inner ear, this causes cochlear fluid to ripple and create a wave motion for the basilar membrane on which the cochlear hair cells sit. This causes the hair cells to move up and down. The stereocilia on top of these hair cells then bend, opening up their channels and permitting chemical intrusion that creates the neural signals conducted by the auditory nerve to the brain.7National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Noise-induced hearing loss. Available at: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/noise-induced-hearing-loss. ,8American Dental Association. Safety tips to prevent hearing loss. Available at: https://success.ada.org/en/wellness/safety-tips-to-avoid-hearing-loss. ,9Murray ID. Hearing loss and tinnitus among dentists. The Hearing Journal, January 2020. Available at: doi: 10.1097/01.HJ.0000651540.52366.f5. (Figure 1)

Hearing loss may be sudden, due to an extremely loud noise (e.g., an exploding grenade). Exposure to lower-intensity noise can cause temporary hearing loss, or permanent hearing loss following continuous or repeated intermittent exposure.7National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Noise-induced hearing loss. Available at: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/noise-induced-hearing-loss. NOHL is caused by sensorineural hearing loss which progresses slowly during long-term exposure to continuous or intermittent noise.8American Dental Association. Safety tips to prevent hearing loss. Available at: https://success.ada.org/en/wellness/safety-tips-to-avoid-hearing-loss. ,9Murray ID. Hearing loss and tinnitus among dentists. The Hearing Journal, January 2020. Available at: doi: 10.1097/01.HJ.0000651540.52366.f5.,10Messano GA, Petti S. General dental practitioners and hearing impairment. J Dent 2012;40:821-8. This results from damage to the cochlear hair cells.7National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Noise-induced hearing loss. Available at: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/noise-induced-hearing-loss. ,9Murray ID. Hearing loss and tinnitus among dentists. The Hearing Journal, January 2020. Available at: doi: 10.1097/01.HJ.0000651540.52366.f5. (Figure 2) An individual may first experience difficulty with high-pitched sounds. Later, it can be difficult to hear at a given volume, sounds may be distorted and conversation can be difficult when there is background noise.8American Dental Association. Safety tips to prevent hearing loss. Available at: https://success.ada.org/en/wellness/safety-tips-to-avoid-hearing-loss.

Tinnitus

Tinnitus may be the first sign of hearing loss and is caused by an imbalance in damage to the inner and outer cochlear hair cells.8American Dental Association. Safety tips to prevent hearing loss. Available at: https://success.ada.org/en/wellness/safety-tips-to-avoid-hearing-loss. Symptoms include a slight intermittent or continuous ringing or whistling sound in the ears, or it may be much more severe.8American Dental Association. Safety tips to prevent hearing loss. Available at: https://success.ada.org/en/wellness/safety-tips-to-avoid-hearing-loss. ,9,11Garner GG, Federman J, Johnson A. Noise induced hearing loss in the dental environment: An audiologist’s perspective. J Georgia Dent Assoc 2002:17-19. Severe tinnitus can impair quality of life due to the body responding to tinnitus as a threat, causing increased stress, hypertension and sleep disturbance.12Jastreboff PJ. Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): Mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosci Res 1990;8(4)221-54. Further, the stress response to noise exposure is believed to be linked to coronary heart disease.13Kerns E, Masterson EA, Themann CL, Calvert GM. Cardiovascular conditions, hearing difficulty, and occupational noise exposure within US industries and occupations. Am J Ind Med 2018;61(6):477-91. doi:10.1002/ajim.22833.

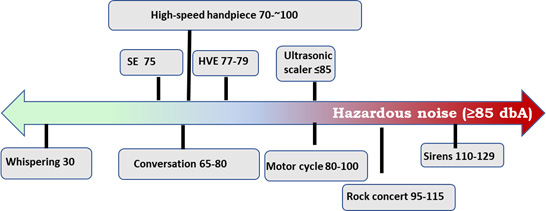

Figure 3. Relative findings on

audible frequency noise levels (db/dbA)14Myers J, John AB, Kimball S, Fruits T. Prevalence of tinnitus and noise‐induced hearing loss in dentists. Noise Health 2016;18(85):347‐54.,15Barek S, Adam O, Motsch JF. Large band spectral analysis and harmful risks of dental turbines. Clin Oral Investig 1999;3(1):49-54.,16Mueller HJ, Sabri ZI, Suchak AJ, McGill S, Standford JW. Noise level evaluation of dental handpieces. J Oral Rehabil 1986;13:279-92.,17Sorainen E, Rytkönen E. Noise level and ultrasound spectra during burring. Clin Oral Investig 2002;6(3):133-6.,18Theodoroff SM, Folmer RL. Hearing loss associated with long-term exposure to high-speed dental handpieces. Gen Dent 2015;63(3):71-6.,19Qsaibati ML, Ibrahim O. Noise levels of dental equipment used in dental college of Damascus University. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2014;11(6):624-30.,20Sampaio Fernandes JC, Carvalho AP, Gallas M, Vaz P, Matos PA. Noise levels in dental schools. Eur J Dent Educ 2006;10(1):32-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2006.00393.x.,21Choosong T, Kaimook W, Tantisarasart R, Sooksamear P, Chayaphum S, Kongkamol C, et al. Noise exposure assessment in a dental school. Safe Health Work 2011;2(4):348-54. doi: 10.5491/SHAW.2011.2.4.348.,22Sorainen E, Rytkönen E. High-frequency noise in dentistry. AIHA J (Fairfax, Va) 2002;63(2):231-3.,23It’s a noisy planet. Protect their hearing. Free sound level meter app from CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. https://www.noisyplanet.nidcd.nih.gov/have-you-heard/cdc-niosh-app.

Sources of Noise in Dental Settings

The main sources of higher-intensity noise in the operatory are high-speed handpieces, ultrasonic scaling devices and high- and low-volume evacuation (HVE, SE). In one study, use of high-speed handpieces resulted in 70.4 to 83.6 dbA, and for a low-speed handpiece reached 70.4 dbA.14Myers J, John AB, Kimball S, Fruits T. Prevalence of tinnitus and noise‐induced hearing loss in dentists. Noise Health 2016;18(85):347‐54. In a second study, noise levels at audible and ultrasonic (inaudible) frequencies for one high-speed handpiece were 95 and 112 dB SPL, respectively.15Barek S, Adam O, Motsch JF. Large band spectral analysis and harmful risks of dental turbines. Clin Oral Investig 1999;3(1):49-54. For two other brands, ultrasonic noise levels ranged from 101 to 115 db SPL. In other studies, high-speed handpieces generated noise up to 87.4 dbA, 76-89 db SPL, 88 – 102 dbA and 89.7 dbA, respectively.16Mueller HJ, Sabri ZI, Suchak AJ, McGill S, Standford JW. Noise level evaluation of dental handpieces. J Oral Rehabil 1986;13:279-92.,17Sorainen E, Rytkönen E. Noise level and ultrasound spectra during burring. Clin Oral Investig 2002;6(3):133-6.,18Theodoroff SM, Folmer RL. Hearing loss associated with long-term exposure to high-speed dental handpieces. Gen Dent 2015;63(3):71-6.,19Qsaibati ML, Ibrahim O. Noise levels of dental equipment used in dental college of Damascus University. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2014;11(6):624-30. In two recent studies in dental school clinics, reported noise levels were below or well below 85 dbA for handpieces and ultrasonic scalers.20Sampaio Fernandes JC, Carvalho AP, Gallas M, Vaz P, Matos PA. Noise levels in dental schools. Eur J Dent Educ 2006;10(1):32-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2006.00393.x.,21Choosong T, Kaimook W, Tantisarasart R, Sooksamear P, Chayaphum S, Kongkamol C, et al. Noise exposure assessment in a dental school. Safe Health Work 2011;2(4):348-54. doi: 10.5491/SHAW.2011.2.4.348. Noise levels of 79.3, 96.5 and 94.8 dBA, respectively, have been found for HVE, obstructed HVE, and use in combination with a high-speed handpiece.14Myers J, John AB, Kimball S, Fruits T. Prevalence of tinnitus and noise‐induced hearing loss in dentists. Noise Health 2016;18(85):347‐54. In a controlled laboratory study with no background noise, measurements of noise at audible and ultrasonic frequencies were taken during simulated procedures. Noise levels for handpieces, an ultrasonic scaler, HVE and SE were 76-82, 83, 77 and 75 dbA, respectively.22Sorainen E, Rytkönen E. High-frequency noise in dentistry. AIHA J (Fairfax, Va) 2002;63(2):231-3. In comparison, whispering and regular conversation generate 30 and 65-80 dB, respectively, while a motor cycle, a rock concert and fire truck sirens generate 80-100, 95 to 115 and 110 to 129 dB, respectively.23It’s a noisy planet. Protect their hearing. Free sound level meter app from CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. https://www.noisyplanet.nidcd.nih.gov/have-you-heard/cdc-niosh-app. The latter can result in some hearing loss in under a minute. (Figure 3)

Prevalence of NOHL in Dentistry

The prevalence of NOHL varies across studies. In one study comparing dentists (mean age 43.7 years) working for at least 10 years with physicians comparable by age and experience, hearing loss (including tinnitus) was 30% and 14.8%, respectively.10Messano GA, Petti S. General dental practitioners and hearing impairment. J Dent 2012;40:821-8. A statistically significant association was found for use of ultrasonic scalers and for high-speed handpieces in use for at least a year. In an audiometry study, the hearing of dentists using/not using high-speed handpieces for >20 years was compared, as well as for students with almost 3 years of clinical experience.18Theodoroff SM, Folmer RL. Hearing loss associated with long-term exposure to high-speed dental handpieces. Gen Dent 2015;63(3):71-6. At 4,000 to 8,000 Hz, statistically significant hearing loss had occurred in the right ear of clinicians using handpieces. Hearing loss in the left ear was statistically significant at 8,000 Hz in comparison to the other dental professionals and students, and at 3000 and 6000 Hz compared to students.

In contrast, no significant difference was found for hearing loss in dental clinicians compared to control groups in other studies.24Alabdulwahhab B, Alduraiby R, Ahmed M, Albatli LI, Alhumain MS, Softah NA, Saleh S. Hearing loss and its association with occupational noise exposure among Saudi dentists: a cross-sectional study. BDJ Open 2, 16006 (2016). doi.org/10.1038/bdjopen.2016.6,25Khaimook W, Suksamae P, Choosong T, Chayarpham S, Tantisarasart R. The prevalence of noise-induced occupational hearing loss in dentistry personnel. Workplace Health Saf 2014;62(9):357-60. However, in one of these studies, audiometry tests revealed a statistically significant difference only for individuals with at least 15 years of experience. In a pilot audiology study, a statistically significant difference in hearing loss was observed at 3000 Hz for dental hygienists with high but not low ultrasonic usage.26Wilson JD, Darby ML, Tolle SL, Sever JC Jr. Effects of occupational ultrasonic noise exposure on hearing of dental hygienists: a pilot study. J Dent Hyg 2002;76(4):262-9. In another study, impaired hearing was observed among dentists, dental assistants and prosthodontists tested using standard and high-frequency threshold audiometry and additional tests. In addition, the use of high-frequency threshold testing enabled detection of hearing loss without which only hearing loss attributable to lower frequencies would have been detected.27Lopes AC, de Melo AD, Santos CC. A study of the high-frequency hearing thresholds of dentistry professionals. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2012;16(2):226-31.

In a survey with 144 respondants, among the 30 to 39 year age group no dentists reported hearing loss. The percentage of dentists ages 40 to 49 years and age 50 and over reporting hearing loss, respectively, was similar to and higher than in the general population.13Kerns E, Masterson EA, Themann CL, Calvert GM. Cardiovascular conditions, hearing difficulty, and occupational noise exposure within US industries and occupations. Am J Ind Med 2018;61(6):477-91. doi:10.1002/ajim.22833. Notably, the reported daily number of hours of use for handpieces, suction and ultrasonic scalers did correlate with self-reported loss of hearing and a higher percentage reported tinnitus than in the general population. Across four other surveys, hearing loss reported by dentists ranged from 3% (22 to 54-year-olds) to 21%, with 37% in one study reporting tinnitus, and among dental nurses surveyed in one study 5% reported hearing loss.28Chowanadisal S, Kukiauttakoon B, Yapong B, Kedjarune U, Leggat PA. Occupational health problems of dentists in southern Thailand. Int Dent J 2000;50:36-40.,29Ali-Ali K, Hashim R. Occupational health problems of dentists in the United Arab Emirates. Int Dent J 2012;62:52-6.,30Daud MK, Noh NF, Sidek DS, Rahman NA, Zakaria MN. Screening of dental staff nurses for noise induced hearing loss. B-ENT 2011;7:245-9.,31Gijbels F, Jacobs R, Princen K, Nackaerts O, Debruyne F. Potential occupational health problems for dentists in Flanders, Belgium. Clin Oral Investig 2006;10(1):8-16. doi:10.1007/s00784-005-0003-6. ,32Elmehdi HM. Noise levels in UAE dental clinics: Health impact on dental healthcare professionals. J Public Health Front 2013;2:189-92. In a survey of dental hygienists with at least 20 years of experience, 40% of respondents reported hearing loss.33Lazar A, Kauer R, Rowe D. Hearing difficulties among experienced dental hygienists: a survey. J Dent Hyg 2015;89(6):378‐83. Among respondents, 17% reported that hearing loss had occurred due to use of ultrasonic scalers and for 9 out of 10 of these individuals an audiologist had confirmed hearing loss. A statistically significant relationship was found for greater use of ultrasonic scalers. The prevalence of hearing loss was 2.5 times that of comparable females in the general population.

Preventing NOHL

Recommendations for prevention of NOHL include hearing tests, use of hearing protection devices (HPD) and considerations for equipment. A baseline test measuring hearing acuity is recommended together with regular annual re-evaluation that would enable early intervention.8American Dental Association. Safety tips to prevent hearing loss. Available at: https://success.ada.org/en/wellness/safety-tips-to-avoid-hearing-loss. High-frequency threshold testing and other non-standard tests, in conjunction with standard audiometry tests, have also been recommended to enhance early hearing loss detection.24Alabdulwahhab B, Alduraiby R, Ahmed M, Albatli LI, Alhumain MS, Softah NA, Saleh S. Hearing loss and its association with occupational noise exposure among Saudi dentists: a cross-sectional study. BDJ Open 2, 16006 (2016). doi.org/10.1038/bdjopen.2016.6 Sound levels can also be monitored. A free sound level meter app for iOS devices is available from NIOSH through iTunes.23It’s a noisy planet. Protect their hearing. Free sound level meter app from CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. https://www.noisyplanet.nidcd.nih.gov/have-you-heard/cdc-niosh-app. (Figure 4) This app is intended for use to measure occupational noise levels and the results can be saved and shared. An external, calibrated microphone is recommended to improve accuracy. Information on hearing protection is also available.

Hearing protection

Hearing protection devices (HPD) may be over-the-counter or custom passive HPD (earplugs), or active HPD with active sound control.34ADA Professional Product Review. Clinician’s perspectives on hearing protection devices. October 2016;11(20:1-5. https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-professional-product-review-ppr/archives/~/media/436B9E501D064A32A42D73770F84D715.ashx. HPD labels include noise reduction ratings (NRR) based on laboratory testing, ranging from an NRR of 0 to 30 db. For example, if the NRR is 20 this indicates a potential noise level reduction from 90 db to 70 db. In reality, poor placement, fit and incorrect use reduce HPD efficacy. It has been suggested that the NRR number of dB be ‘derated’ (reduced) for real-life situations.35Insight. How it works: Noise reduction ratings. October, 2019. https://www.soneticscorp.com/how-it-works-noise-reduction-ratings/.

Passive earplugs provide a physical barrier that reduces noise without differentiating by noise level, thereby impeding communication with patients.34ADA Professional Product Review. Clinician’s perspectives on hearing protection devices. October 2016;11(20:1-5. https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-professional-product-review-ppr/archives/~/media/436B9E501D064A32A42D73770F84D715.ashx. In contrast, active HPD are battery-operated electronic devices that attenuate hazardous noise, reducing the noise level without affecting non-hazardous noise.34ADA Professional Product Review. Clinician’s perspectives on hearing protection devices. October 2016;11(20:1-5. https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-professional-product-review-ppr/archives/~/media/436B9E501D064A32A42D73770F84D715.ashx. These devices are available as musicians HPD and as active HPD sold in the dental market under several brands (e.g., Music PRO, Denplugs, EarAID, and QuietOn). HPD can also be custom-fitted by an audiologist. Active HPD offer protection against hazardous noise without impacting communication with patients and the dental team, and rate well for comfort and appearance.8American Dental Association. Safety tips to prevent hearing loss. Available at: https://success.ada.org/en/wellness/safety-tips-to-avoid-hearing-loss. ,11Garner GG, Federman J, Johnson A. Noise induced hearing loss in the dental environment: An audiologist’s perspective. J Georgia Dent Assoc 2002:17-19.,34ADA Professional Product Review. Clinician’s perspectives on hearing protection devices. October 2016;11(20:1-5. https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-professional-product-review-ppr/archives/~/media/436B9E501D064A32A42D73770F84D715.ashx.

Equipment and Environmental Considerations

Poor equipment maintenance is associated with increased noise during use.10Messano GA, Petti S. General dental practitioners and hearing impairment. J Dent 2012;40:821-8.,17Sorainen E, Rytkönen E. Noise level and ultrasound spectra during burring. Clin Oral Investig 2002;6(3):133-6.,18Theodoroff SM, Folmer RL. Hearing loss associated with long-term exposure to high-speed dental handpieces. Gen Dent 2015;63(3):71-6.,20Sampaio Fernandes JC, Carvalho AP, Gallas M, Vaz P, Matos PA. Noise levels in dental schools. Eur J Dent Educ 2006;10(1):32-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2006.00393.x. Proper maintenance of handpieces, ultrasonic scalers and compressors in accordance with the manufacturer’s IFU not only prolongs the life of these devices, it can also help prevent hearing loss.10Messano GA, Petti S. General dental practitioners and hearing impairment. J Dent 2012;40:821-8.,18Theodoroff SM, Folmer RL. Hearing loss associated with long-term exposure to high-speed dental handpieces. Gen Dent 2015;63(3):71-6. Noise level is also one of many considerations in selecting dental equipment. Office soundproofing, baffle drapes, resilient floors and noise-mitigating ceilings can also help to contain noise levels, as does positioning the compressor far away from operatories. (Table 1)

| Table 1. Recommendations on preventing NOHL |

|---|

| Baseline hearing test and regular annual re-evaluation |

| Adjunctive high-frequency threshold testing, other tests24Alabdulwahhab B, Alduraiby R, Ahmed M, Albatli LI, Alhumain MS, Softah NA, Saleh S. Hearing loss and its association with occupational noise exposure among Saudi dentists: a cross-sectional study. BDJ Open 2, 16006 (2016). doi.org/10.1038/bdjopen.2016.6 |

| Use of hearing protection devices (HPD) |

| Proper equipment maintenance |

| Office design and layout considerations |

Conclusions

Several studies have demonstrated noise levels in excess of the recommended threshold level. Results from studies and surveys vary, while length of years worked, duration of workdays and usage of noise-generating equipment is associated with NOHL. In addition, impaired communication resulting from use of HPD has been a barrier to use and low levels of adoption have been reported.18Theodoroff SM, Folmer RL. Hearing loss associated with long-term exposure to high-speed dental handpieces. Gen Dent 2015;63(3):71-6.,33Lazar A, Kauer R, Rowe D. Hearing difficulties among experienced dental hygienists: a survey. J Dent Hyg 2015;89(6):378‐83. Longitudinal studies assessing hearing acuity and the prevalence of NOHL among dental professionals, as well as studies on educational interventions that would increase HPD use have been recommended.14Myers J, John AB, Kimball S, Fruits T. Prevalence of tinnitus and noise‐induced hearing loss in dentists. Noise Health 2016;18(85):347‐54.,18Theodoroff SM, Folmer RL. Hearing loss associated with long-term exposure to high-speed dental handpieces. Gen Dent 2015;63(3):71-6.,36Hyson JM Jr. The air turbine and hearing loss: are dentists at risk? J Am Dent Assoc 2002;133(12):1639-42. It is recommended that dental professionals have regular hearing tests, wear HPD and consider equipment and environmental factors. It behooves the dental team to routinely use HPD, and active sound control HPD offers a solution that preserves communication with patients and the team. Ultimately, NOHL is preventable.

References

- 1.Dominy SS, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv. 2019;5(1):eaau3333 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30746447.

- 2.Sadrameli M, et al. Linking mechanisms of periodontitis to Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020;33(2):230-8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32097126.

- 3.Borsa L, et al. Analysis the link between periodontal diseases and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34501899.

- 4.Costa MJF, et al. Relationship of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of pre-clinical studies. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(3):797-806 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33469718.

- 5.Munoz Fernandez SS, Lima Ribeiro SM. Nutrition and Alzheimer disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(4):677-97 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30336995.

- 6.Aquilani R, et al. Is the Brain Undernourished in Alzheimer’s Disease? Nutrients. 2022;14(9) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35565839.

- 7.Fukushima-Nakayama Y, et al. Reduced mastication impairs memory function. J Dent Res. 2017;96(9):1058-66 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28621563.

- 8.Kim HB, et al. Abeta accumulation in vmo contributes to masticatory dysfunction in 5XFAD Mice. J Dent Res. 2021;100(9):960-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33719684.

- 9.Miura H, et al. Relationship between cognitive function and mastication in elderly females. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30(8):808-11 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12880404.

- 10.Lexomboon D, et al. Chewing ability and tooth loss: association with cognitive impairment in an elderly population study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):1951-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23035667.

- 11.Elsig F, et al. Tooth loss, chewing efficiency and cognitive impairment in geriatric patients. Gerodontology. 2015;32(2):149-56 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24128078.

- 12.Kim EK, et al. Relationship between chewing ability and cognitive impairment in the rural elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;70:209-13 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28214402.

- 13.Kim MS, et al. The association between mastication and mild cognitive impairment in Korean adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(23):e20653 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32502052.

- 14.Cardoso MG, et al. Relationship between functional masticatory units and cognitive impairment in elderly persons. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(5):417-23 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30614023.

- 15.Popovac A, et al. Oral health status and nutritional habits as predictors for developing alzheimer’s disease. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(5):448-54 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34348313.

- 16.Park T, et al. More teeth and posterior balanced occlusion are a key determinant for cognitive function in the elderly. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33669490.

- 17.Lin CS, et al. Association between tooth loss and gray matter volume in cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14(2):396-407 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32170642.

- 18.Kumar S, et al. Oral health status and treatment need in geriatric patients with different degrees of cognitive impairment and dementia: a cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(6):2171-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34322409.

- 19.Delwel S, et al. Chewing efficiency, global cognitive functioning, and dentition: A cross-sectional observational study in older people with mild cognitive impairment or mild to moderate dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:225 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33033478.

- 20.Da Silva JD, et al. Association between cognitive health and masticatory conditions: a descriptive study of the national database of the universal healthcare system in Japan. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13(6):7943-52 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33739304.

- 21.Galindo-Moreno P, et al. The impact of tooth loss on cognitive function. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26(4):3493-500 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34881401.

- 22.Stewart R, et al. Adverse oral health and cognitive decline: The health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):177-84 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23405916.

- 23.Dintica CS, et al. The relation of poor mastication with cognition and dementia risk: A population-based longitudinal study. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(9):8536-48 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32353829.

- 24.Kim MS, Han DH. Does reduced chewing ability efficiency influence cognitive function? Results of a 10-year national cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(25):e29270 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35758356.

- 25.Ko KA, et al. The Impact of Masticatory Function on Cognitive Impairment in Older Patients: A Population-Based Matched Case-Control Study. Yonsei Med J. 2022;63(8):783-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35914761.

- 26.Garre-Olmo J. [Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias]. Rev Neurol. 2018;66(11):377-86 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29790571.

- 27.Stephan BCM, et al. Secular Trends in Dementia Prevalence and Incidence Worldwide: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(2):653-80 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30347617.

- 28.Lopez OL, Kuller LH. Epidemiology of aging and associated cognitive disorders: Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;167:139-48 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31753130.

- 29.Ono Y, et al. Occlusion and brain function: mastication as a prevention of cognitive dysfunction. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(8):624-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20236235.

- 30.Kubo KY, et al. Masticatory function and cognitive function. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2010;87(3):135-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21174943.

- 31.Chen H, et al. Chewing Maintains Hippocampus-Dependent Cognitive Function. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12(6):502-9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26078711.

- 32.Azuma K, et al. Association between Mastication, the Hippocampus, and the HPA Axis: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(8) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28771175.

- 33.Chuhuaicura P, et al. Mastication as a protective factor of the cognitive decline in adults: A qualitative systematic review. Int Dent J. 2019;69(5):334-40 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31140598.

- 34.Lopez-Chaichio L, et al. Oral health and healthy chewing for healthy cognitive ageing: A comprehensive narrative review. Gerodontology. 2021;38(2):126-35 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33179281.

- 35.Tada A, Miura H. Association between mastication and cognitive status: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;70:44-53 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28042986.

- 36.Ahmed SE, et al. Influence of Dental Prostheses on Cognitive Functioning in Elderly Population: A Systematic Review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2021;13(Suppl 1):S788-S94 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34447202.

- 37.Tonsekar PP, et al. Periodontal disease, tooth loss and dementia: Is there a link? A systematic review. Gerodontology. 2017;34(2):151-63 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28168759.

- 38.Nangle MR, Manchery N. Can chronic oral inflammation and masticatory dysfunction contribute to cognitive impairment? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2020;33(2):156-62 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31895157.

- 39.Nakamura T, et al. Oral dysfunctions and cognitive impairment/dementia. J Neurosci Res. 2021;99(2):518-28 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33164225.

- 40.Weijenberg RAF, et al. Mind your teeth-The relationship between mastication and cognition. Gerodontology. 2019;36(1):2-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30480331.

- 41.Asher S, et al. Periodontal health, cognitive decline, and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(9):2695-709 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36073186.

- 42.Lin CS. Revisiting the link between cognitive decline and masticatory dysfunction. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29304748.

- 43.Wu YT, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time – current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(6):327-39 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28497805.

- 44.National Psoriasis Foundation. Soriatane (Acitretin). https://www.psoriasis.org/soriatane-acitretin/.

- 45.National Psoriasis Foundation. Current Biologics on the Market. https://www.psoriasis.org/current-biologics-on-the-market/.

- 46.Dalmády S, Kemény L, Antal M, Gyulai R. Periodontitis: a newly identified comorbidity in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2020;16(1):101-8. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1700113.

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2023/05/Fiona-Collins-thumbnail-1-3.jpg)

:sharpen(level=0):output(format=jpeg)/up/2020/11/hearing-loss-in-dentistry-2.jpg)